North Carolina’s Medicaid program won’t shift to managed-care benefits as scheduled early next year, the largest casualty to date of the months-long budget stalemate between Democratic Governor Roy Cooper and Republican lawmakers.

Although the Department of Health and Human Services’ Tuesday announcement about the rollout suspension was anticipated, the indefinite delay represents a significant failure for both the legislative and executive branches.

Both sides quickly blamed the other for the postponement, which will waste state dollars when the shift is supposed to save taxpayer money.

Legislators and the Cooper administration hadn’t been able to reach an agreement on final spending and program changes to get services started February 1 for about 1.6 million Medicaid recipients. DHHS Secretary Mandy Cohen had said a deal was needed by mid-November. Legislators adjourned for the year last week.

“We just can’t go ahead and move on in the face of uncertainty,” Cohen told The Associated Press in an interview, adding that no new start date will be set now. “We’ll wait for the legislature to come back in January and see where we go.”

The impasse largely centered around Cooper’s efforts to expand Medicaid to hundreds of thousands of low-income residents through the 2010 federal health care law. Although managed care can happen without expansion, Cooper has attempted to connect the two.

The governor has vetoed two bills containing the necessary managed-care language. One is the larger two-year budget approved by GOP lawmakers that he vetoed in June. The other is a stand-alone measure focused on managed care only that he vetoed in August. Cooper said in his veto message that health care needed to be addressed “comprehensively.”

The GOP-controlled General Assembly began the Medicaid “transformation” process with a 2015 law, and Cooper’s DHHS had been working since he took office to implement these changes. It awarded multibillion-dollar contracts to five health care entities that were planning to serve Medicaid recipients.

Medicaid is moving from a traditional fee-for-service model to one in which four private insurers and a physicians’ partnership will receive fixed monthly payments for every patient seen. Health officials say the changes should lead to improved health outcomes and more fiscal stability for Medicaid, which spends about $4 billion in state tax dollars annually. The federal government pays an additional $12 billion.

Sen. Joyce Krawiec, a Forsyth County Republican, warned in a news release earlier Tuesday that Cooper’s veto of the stand-alone bill “will force insurers to lay off thousands of people they’ve already hired as part of the yearslong plan to transform Medicaid.”

Senate Republicans couldn’t immediately provide backup to substantiate that level of job losses. Cohen wouldn’t comment on specifics about employment except that no DHHS employees will lose their jobs. “She is correct there are consequences to their actions,” Cohen told the AP.

Cohen said DHHS will continue to carry out the fee-for-service plan, and patients will continue to receive health services. The department will alert Medicaid consumers to the delay.

Related Stories

‹

Financial Incentive for More Medicaid Draws Mixed ReactionA financial carrot for North Carolina to expand Medicaid to hundreds of thousands low-income adults is raising already elevated hopes among Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper and allies that the General Assembly will finally adopt it this year. But those aspirations remain uncorroborated by GOP leaders who remain wary of expansion or don’t see it happening. […]

Cooper on Election Results: 'There Is a Lot of Status Quo'North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper said in a news conference on Thursday that he will continue to push forward with his goal of expanding Medicaid at a time when voters decided to maintain GOP control of both chambers of the Legislature. “There is a lot of status quo, but I do think that my election, and […]

![]()

North Carolina Medicaid Expansion Advocates 'Mad' as Bill IdlesNorth Carolina remains among the dozen or so states that haven’t agreed to expand Medicaid to more of the working poor amid a lingering budget stalemate and continued skepticism among top Senate Republicans about the idea. The General Assembly met Tuesday for a session in which legislation related to health care access was among potential […]

N. Carolina Hospitals Offer New Medicaid Expansion ProposalWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON North Carolina’s hospitals and hospital systems on Friday unveiled an offer that could shake up stalled negotiations to pass legislation that would expand Medicaid to cover hundreds of thousands of low-income adults in the state. The North Carolina Healthcare Association said the offer sent to Republican legislative leaders and Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper also […]

Cooper Seeks Big Debt Package, Pay Hikes, Medicaid ExpansionWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON North Carolina Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper on Wednesday proposed a spending and borrowing spree by state government that he said is critical to fulfilling education, health care and infrastructure demands that were evident before the pandemic but have been exacerbated since. With state coffers filled with unspent funds and $5 billion […]

![]()

NC Virus Relief Aid Heads to Cooper as General Assembly EndsThe North Carolina legislature finalized a plan Thursday to spend $1.1 billion of the state’s remaining COVID-19 relief funds from Washington, including direct cash payments to nearly 2 million families. The package, which also provides a $50 uptick in weekly unemployment benefits and more funds for virus testing, tracing and personal protective equipment, cleared its […]

![]()

N. Carolina Medicaid Bill Delays Managed Care Until Mid-2021North Carolina’s Medicaid program wouldn’t shift most of its patients to managed care for another year under a funding measure given tentative approval on Tuesday by the state Senate. The July 1, 2021, start date is contained in a bill that also locates another $460 million to cover additional expenses during the next fiscal year […]

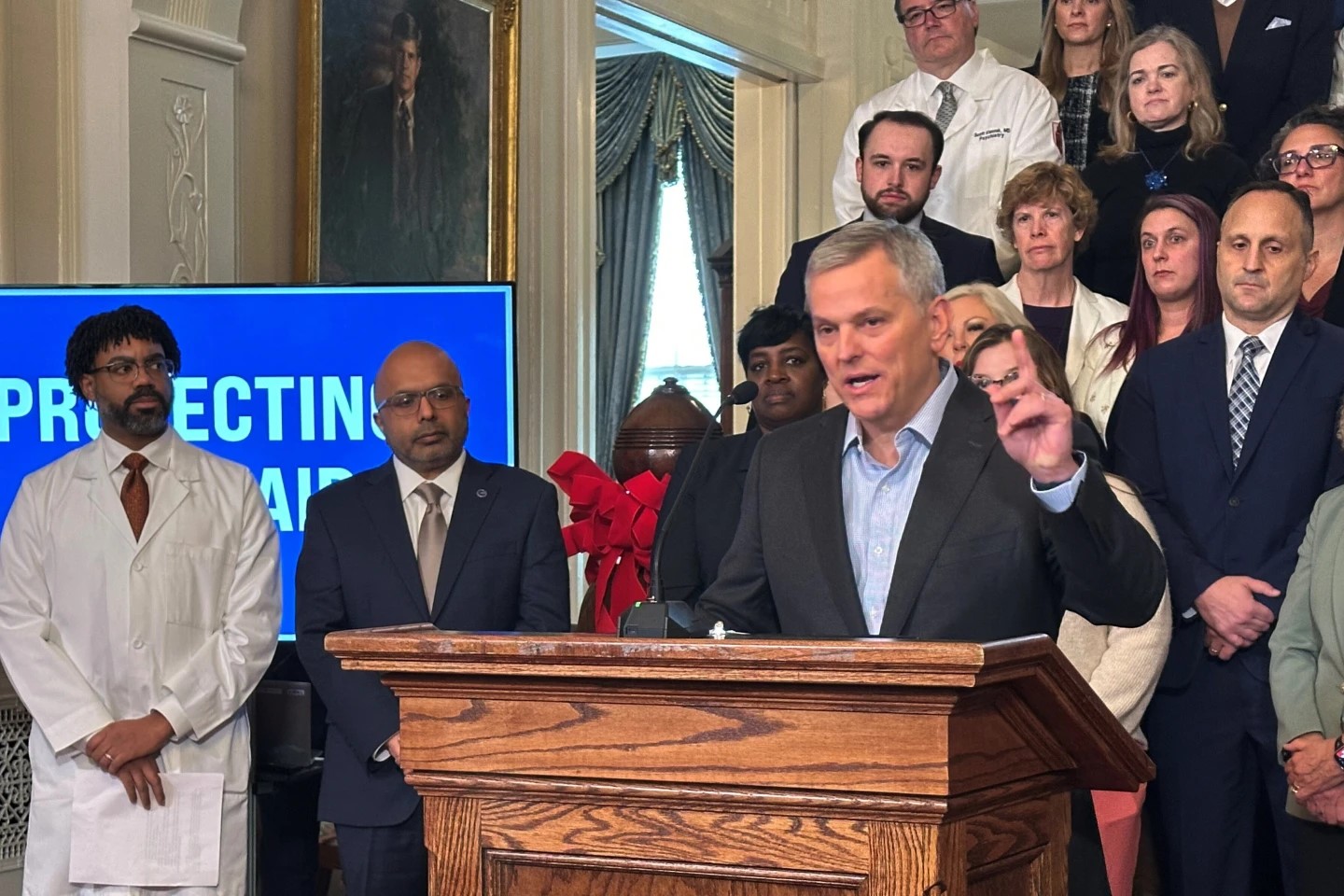

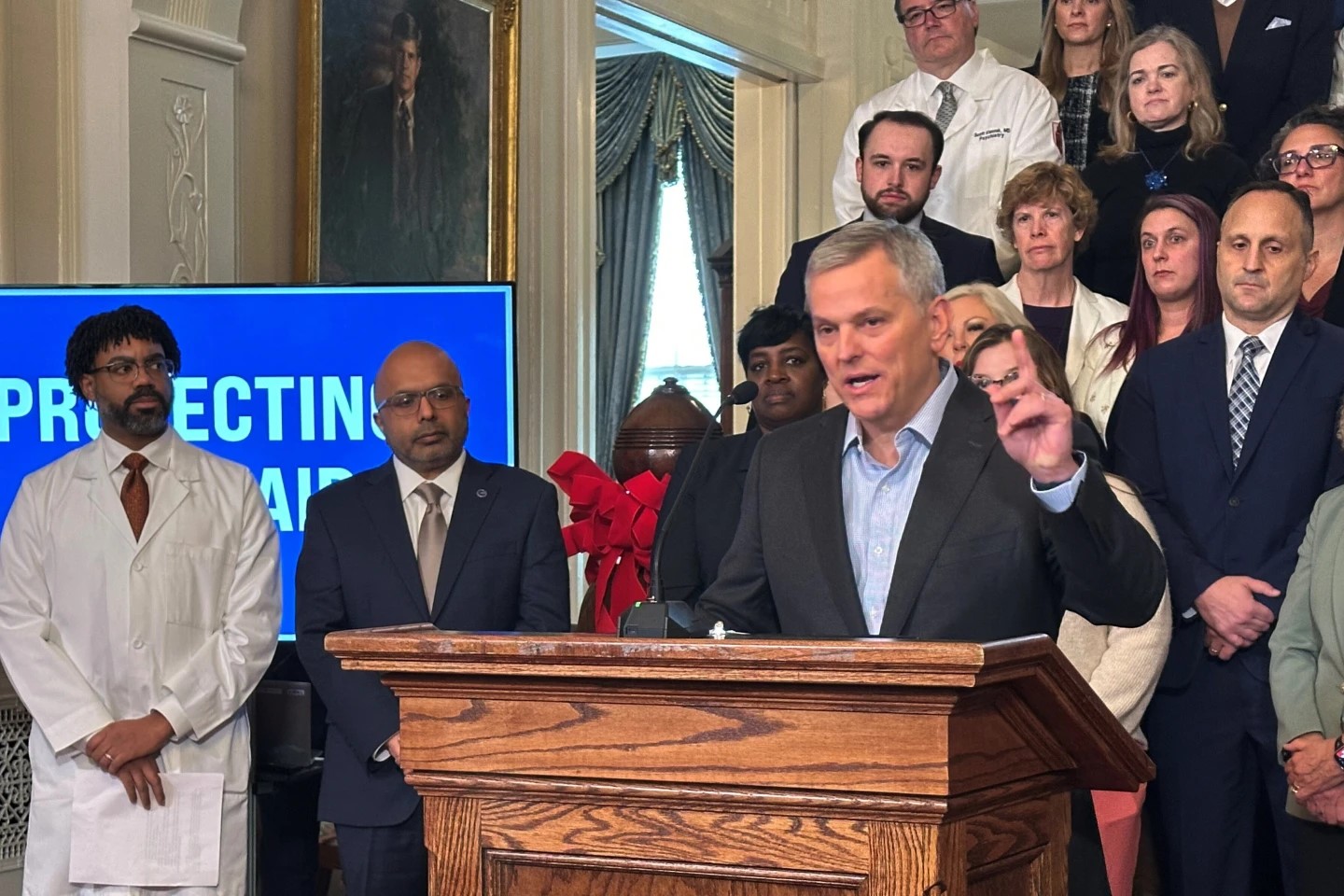

North Carolina Gov. Stein Cancels Medicaid Rate Cuts Amid Legal and Legislative BattlesNorth Carolina Democratic Gov. Josh Stein is canceling Medicaid reimbursement rate reductions he initiated over two months ago, preserving in the short term access to care for vulnerable patients.

North Carolina Effort Wipes Out $6.5B in Medical Debt for 2.5M PeopleMore than 2.5 million North Carolina residents are getting over $6.5 billion in medical debt eliminated through a state government effort that offered hospitals extra Medicaid funds.

North Carolina Medicaid Patients Face Care Access Threat as Funding Impasse ContinuesNorth Carolina Medicaid patients face reduced access to services as an legislative impasse over state Medicaid funding extends further.

›