As North Carolina politicians gear up for a big debate this year over whether to finally expand Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, the state is already prepping for dramatic changes in how it pays for and treats most current enrollees.

The state Department of Health and Human Services is expected to announce this week which insurance and health care provider groups won managed-care contracts to serve about 1.6 million Medicaid recipients — mostly poor children, older adults and the disabled.

These contracts could be valued at $6 billion annually for up to five years, or the largest procurement ever by North Carolina’s health agency. The first patients would be transferred to the new system next November, with others moving over in February 2020.

“It’s a major transformation in North Carolina,” said Rep. Donny Lambeth, a Forsyth County Republican who helped pass the 2015 law starting the switch to Medicaid managed care. “It is a risk model where the providers are fully at risk, and it is a significant change.”

North Carolina is shifting most Medicaid programs from traditional fee-for-service coverage to those in which companies or medical networks get flat monthly amounts for each patient covered. Instead of paying doctors and hospitals for every test and procedure, Medicaid would allow these “prepaid health plans” to keep whatever’s left over after medical expenses and activities. While keeping patients healthier could boost plan profits, sicker patients could mean losses.

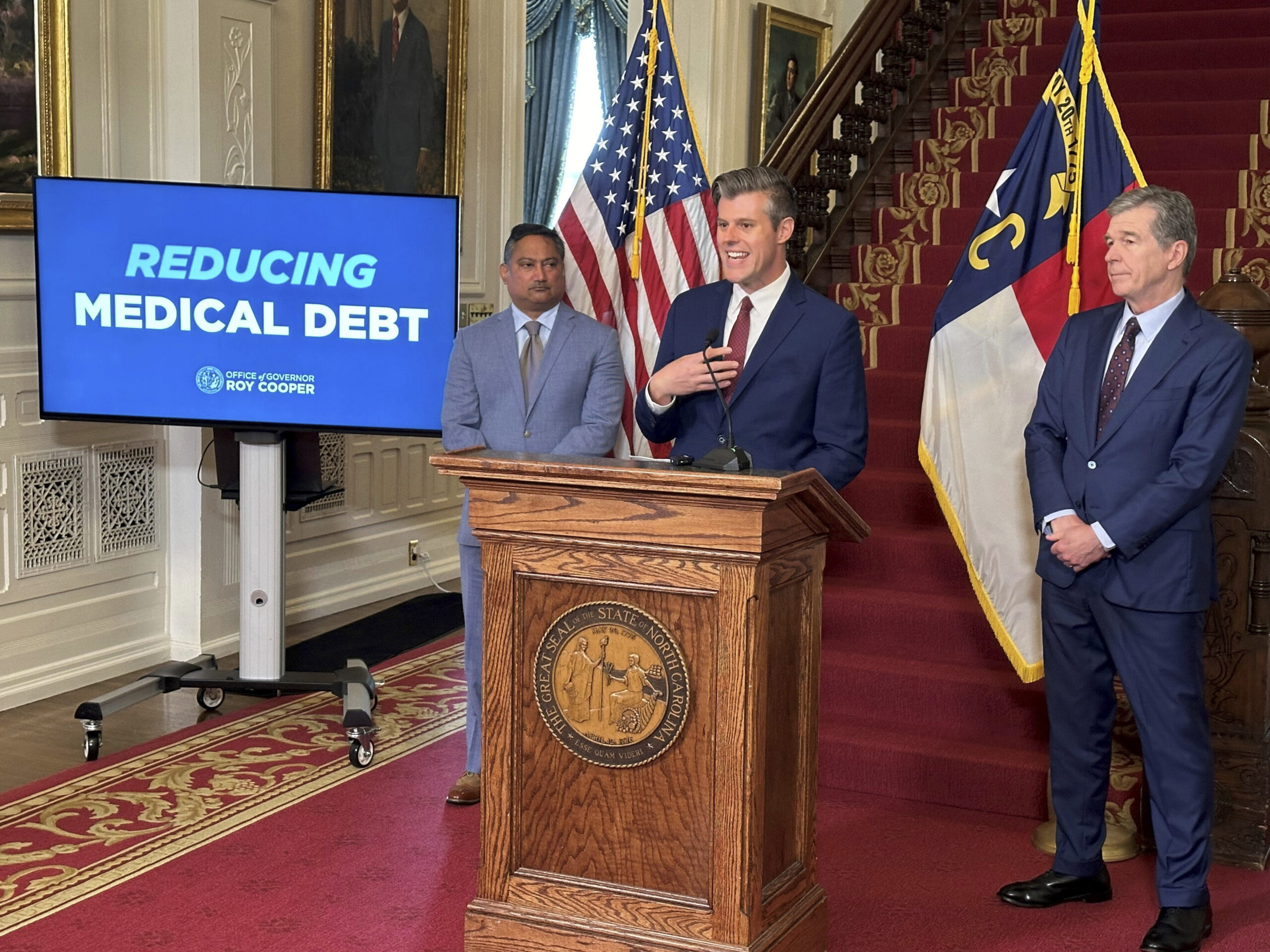

The alterations should influence the debate over whether it makes sense at the same time to bring another 300,000 to 500,000 new low- and middle-income enrollees on board through expansion. Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper and party allies, who made legislative seat gains last November that gives them more negotiating leverage, are making expansion a top priority this year. Legislative Republicans have blocked it for years.

The state said it would award up to four statewide managed-care contracts and up to two covering each of six regions, as a way to encourage competition.

Eight vendors applied, including insurance giants Aetna, UnitedHealth Care and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, as well as medical providers who have partnered with companies with managed-care experience in other states. One statewide bidder, called “My Health by Health Providers ,” is comprised of 12 local hospital systems and New Mexico-based insurer Presbyterian Healthcare Systems.

The state Department of Health and Human Services said last week it couldn’t comment until awards are announced.

Lambeth, former president of North Carolina Baptist Hospital, said the lack of smaller bidders may be due to hospital systems worried about taking bold chances alone: “If they don’t do it right, they could lose a lot of money.”

Rep. Verla Insko, an Orange County Democrat who works on health care issues, supports expansion. She’s worried about the bumps along the road with the broader Medicaid overhaul. She points to past problems with government managed-care entities for people with mental illness, substance abuse problems and developmental disabilities.

“Any time you have a huge system change there are going to be mistakes made, and it’s really important when that happens that we get the right answers,” Insko said. Lambeth said legislators talked with Medicaid directors from elsewhere to try to avoid managed-care pitfalls in other states.

Professor Don Taylor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, said there’s a reasonable chance Medicaid managed care will succeed in places like Raleigh and Charlotte. But he said it will be difficult in many rural areas “because there’s not enough people that are insured and there’s not enough providers.”

Taylor said that’s where Medicaid expansion could generate more enrollees, attracting doctors and giving small hospitals more revenue.

Lambeth, who supports a form of Medicaid expansion, believes the managed-care system can handle a large influx of enrollees. But GOP Sen. Ralph Hise of Mitchell County said discussions over expansion have less to do with system capacity and more whether Washington will provide flexibility in allowing expansion to cover high-expense patients. Still, Hise said, managed care is the right way to treat current Medicaid enrollees.

“It’s a better system,” Hise said.