With the rise of the Internet and social media, it’s often said that we’re living in an Information Age. But the corresponding rise of fake news sites and bogus conspiracy theories means we’re living in a Misinformation Age as well.

What can be done about the spread of misinformation in public discourse? And how worried should we be about it?

Duke University recently held an online forum on the subject of “Navigating Fake News” – which, true to the complexity of the issue, offered as many new questions as answers.

“I remember on the dawn of the Internet age, thinking how marvelous the Internet was going to be – it was going to empower everyone, it was going to bring information to everyone, it was going to be great for journalism,” says Duke University journalism professor Bill Adair. “And now here we are twenty years later, and there’s just so much misinformation.”

The rise of misinformation in social media, coupled with a rise in hate speech, has led many to call for social-media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to be more active in policing the content that gets posted there.

Duke public policy professor Matthew Perault says there are some potential advantages in being more aggressive in removing online misinformation. “One is that you might limit the aggregate amount of misinformation,” he says; “[and] a second is that you might reduce the impact of misinformation on particularly vulnerable communities, including communities of color.”

But Perault also says there may be serious disadvantages, particularly the danger of overly restricting speech in unintended and harmful ways.

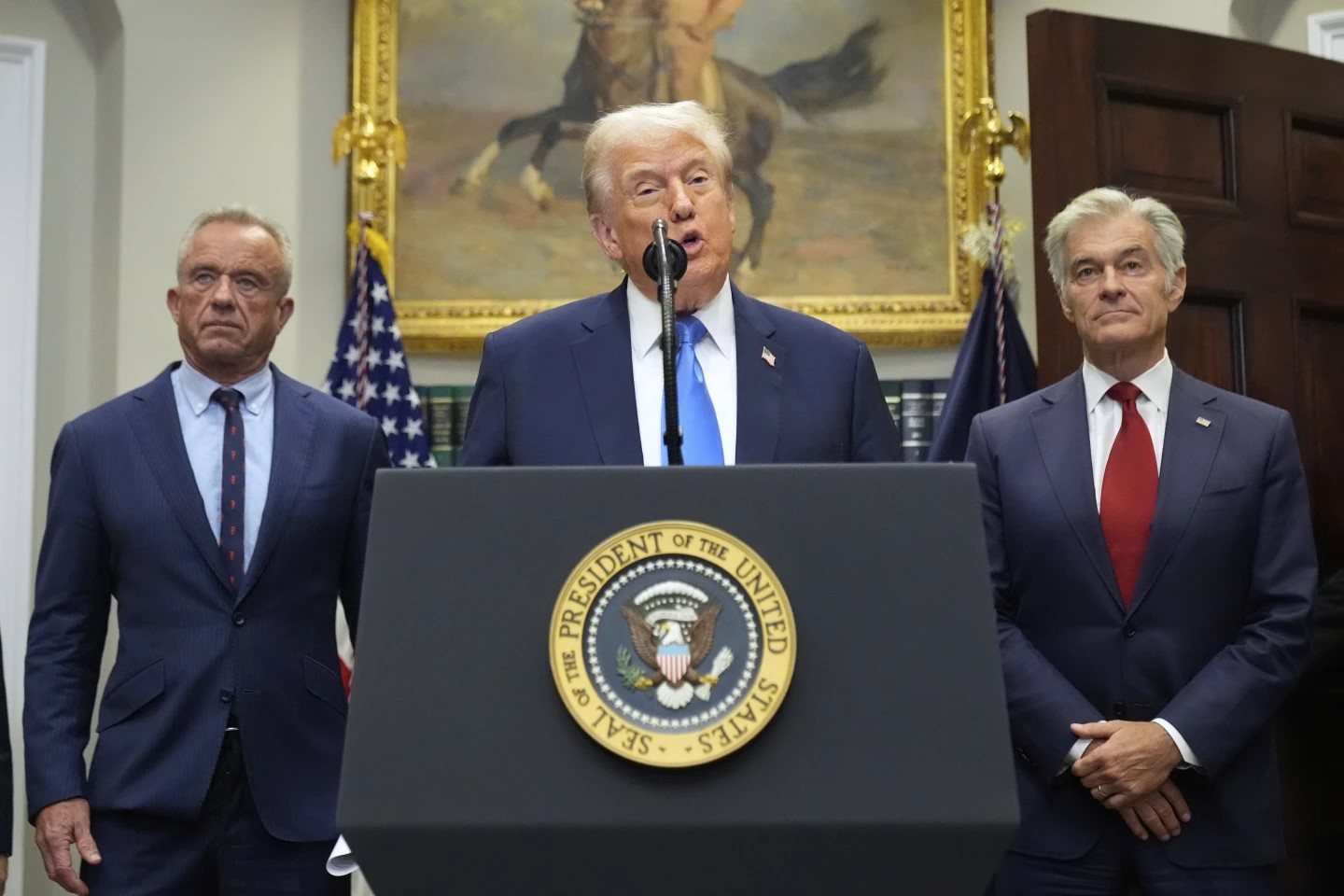

And he adds that taking steps to remove misinformation may not have much of an impact anyway. “There was a lot of attention, for instance, of the differential treatment of President Trump’s tweets by Twitter and Facebook,” he says. “Facebook elected to not add article context, [while] Twitter did…

“[But] we still don’t actually know the impact that Twitter’s approach had. I think it’s unlikely that Twitter’s approach changed many minds: I think people tend to either agree with the President or disagree with the President, and I’m not sure adding additional context would change that.”

But how concerned should we be about misinformation in the first place?

Duke political scientist Sunshine Hillygus says there is a lot of it out there – but that may not matter too much.

“Widespread existence is not the same as widespread impact,” she says.

For instance, Hillygus recently studied the effect of Russian misinformation trolls – bogus Twitter accounts, pretending to be Americans and spreading fake information. Lots of us have been exposed to these bots – but do they actually have an impact on the way we think?

“We found precisely zero effect on public opinion and polarization,” Hillygus says.

Likewise, she adds, even though we’re surrounded by lots of misinformation, “there has not really been as much of a change as you might expect” in how informed Americans are on the issues, compared to years past.

But Hillygus adds that one of the primary reasons we’re not persuaded by misinformation is that most of us are already locked into our opinions anyway. “Persuasion is very, very hard,” she says, “in part because people are very polarized.”

That suggests that the larger problem may not be misinformation, but rather political polarization.

Bill Adair agrees that polarization is a major problem – adding that one of the unintended consequences of the Internet is that it amplifies the voices of political extremists.

“The small percentage of people who had conspiracy beliefs couldn’t get together very easily (in the past) because they didn’t know who the other people were,” Adair says, “but the digital age has made it much easier for them to get together.

“And (it’s also) made it much easier for media organizations to report on that and suggest that (extremism) is a bigger thing than it is.”

Sunshine Hillygus agrees – but adds that it’s critical to keep in mind that extremism may not be as prevalent as it sometimes seems. In spite of everything – the misinformation, the extremism, and the partisan polarization – Hillygus’ research finds that Americans today still do agree on a lot of critical issues.

“There’s a lot of coverage, for instance, of examples where someone is not wearing a mask and confronts someone in a store, but we’re seeing overwhelming support for the use of masks on both sides of the aisle,” Hillygus says. “A recent Ipso poll found that just three percent of people said they never wore a mask when they left their house.”

And to the extent that that’s the case, Hillygus suggests one key issue may come down not to the spread of online misinformation – but simply to a failure of leadership, both on the part of journalists who focus on conflict and elected officials who emphasize discord.

“To some extent,” she concludes, “the real problem and puzzle is: why is it that our political system is not adequately representing the views of the American public where there is common agreement?”

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees. You can support local journalism and our mission to serve the community. Contribute today – every single dollar matters.