HIV has infected over 70 million people according to the World Health Organization, but virologists at UNC-Chapel Hill are now one step closer to stopping the spread of the insidious pathogen.

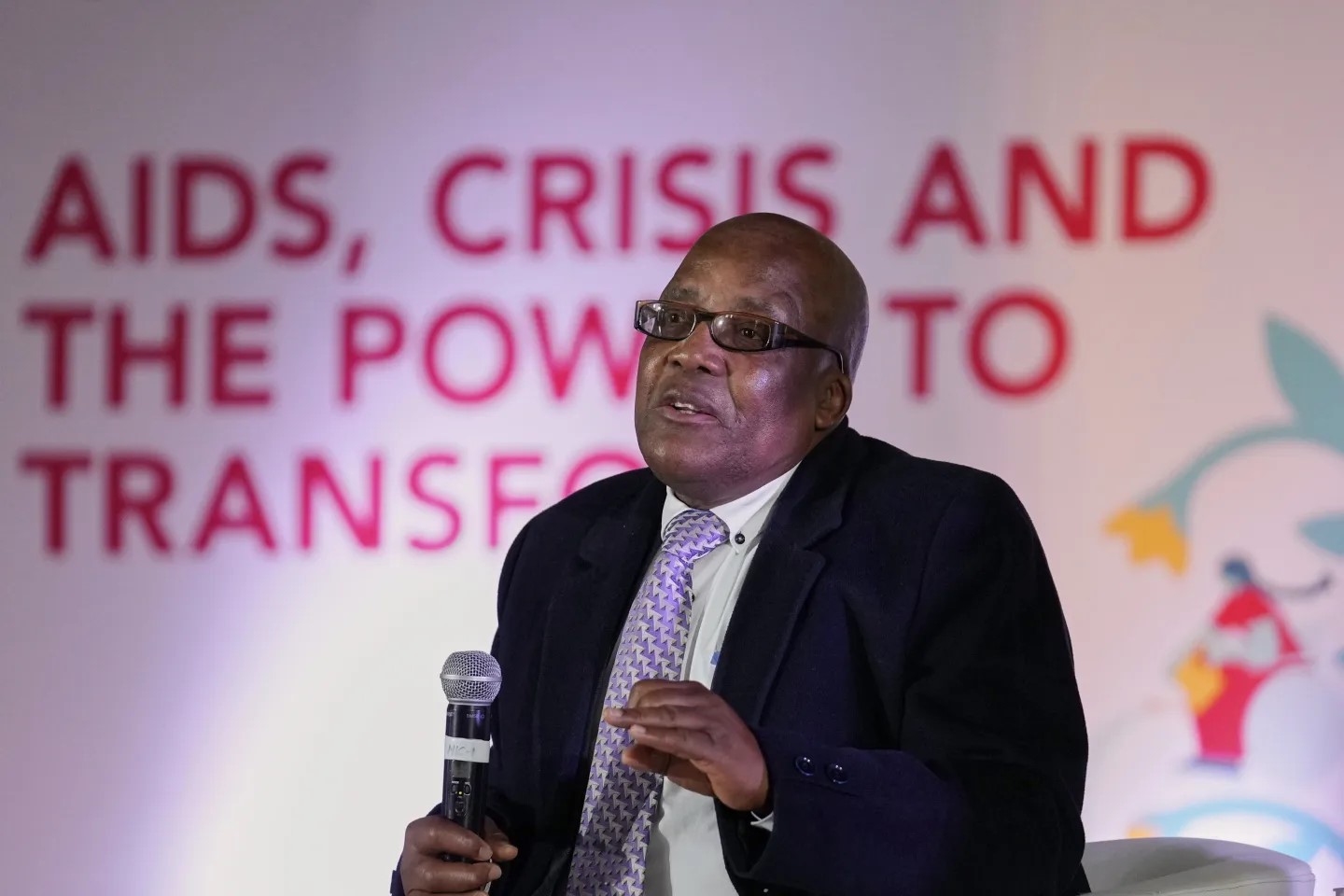

The effective but temporary nature of current HIV treatments was the impetus for Dr. J. Victor Garcia and his team to consider how the pathogen circumvents eradication in the body.

“We have very, very good, reliable, robust therapies that suppress the virus from growing in patients, and these individuals can lead virtually normal lives for many, many years,” he explained. “Despite the success of therapeutic interventions, we cannot rid the body of the virus.”

Antiretroviral drugs to combat the effects of HIV were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1995, but Garcia noted that these drugs treat the symptoms and not the cause.

“The virus remains; it persists for the life of the patient, and it’s very difficult to assess what is happening because we can only look at what is present in blood,” he relayed. “In blood, we can’t find the virus in treated patients, but as soon as you stop antiretroviral therapy, the virus comes raging back, just like you are infected for the first time.”

This conundrum led Garcia and his team to isolate tissue-based cells called macrophages and study the way in which they react to blood-oriented antiretroviral therapy in animal models.

Those models reinforced what virologists already knew about the fleeting effects of HIV medication, but they also enabled Garcia and company to discover the evasion strategy of the pathogen.

“The virus came back, and it came back from macrophages, and what that establishes is that macrophages serve as a reservoir where the virus can hide quietly in vivo and then can reignite the infection when the therapy is stopped,” he revealed.

Armed with the knowledge that macrophages become reservoirs for HIV that reintroduce the pathogen to the host body, Garcia and his colleagues were ready to submit their findings for review.

“We’ve now identified a target that must be considered in our efforts to try to find a cure for HIV/AIDS, because if we are able to rid the body of all the infected T cells present and have residual macrophages that still carry the virus, then we’ll be back to square one,” he affirmed.

After a two-month peer review process, those findings were approved and published last week in Nature Medicine, which is the highest-cited journal in preclinical medicine.

Garcia speculated that new comprehensive therapies targeting multiple organic HIV repositories are likely to go into production based on the research carried out by his team.

“What we now have is the advantage to be able to evaluate the therapeutic interventions having [been] developed for T cells to see if they work in macrophages,” he stated. “If they do, then problem solved, but if they don’t, they will be able to target macrophages specifically to be able to use combination therapies that will target all the possible reservoirs present in the body.”

The support extended by the local community to his team was not lost on Garcia, who voiced his appreciation for the superb quality of students and facilities at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“I don’t think there’s any better place in the world to carry out this work, and I am very humbled to be part of it,” he emphasized. “I think that the support that UNC has given us and the community as a whole in Chapel Hill and in North Carolina for these efforts has been second to none.”

Funding for the research carried out by Garcia and company was provided in part by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Photo from Encyclopædia Britannica.