Since its approval as a prescription drug in 2015, naloxone and its name brand Narcan have been used to stop opioid overdoses across the United States. Fatal overdoses continue to rise, though – especially with the prevalence of fentanyl, which is a synthetic and strong opioid.

Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration took a step to try and continue limiting overdose deaths by approving Narcan as an over-the-counter drug.

Delesha Carpenter is an associate professor and researcher at UNC’s Eshelman School of Pharmacy. As the Executive Vice Chair for the school’s Division of Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Policy, she says the FDA’s ruling is not surprising, but welcome.

Carpenter says naloxone is most common in a nasal spray form and is used on someone who has become unresponsive or is showing symptoms of an opioid overdose.

“You have different receptors in your brain,” she says, “and opioids bind to those receptors. What naloxone does is it comes in and kicks those opioids off that receptor and once it does that, it stops the respiratory depression and other effects of an overdose.

“It gets people to start breathing again, essentially – and it does it very quickly,” Carpenter adds.

Part of Carpenter’s work is directing a research network for pharmacists in rural communities across seven states. She says that includes doing training to address and lower the stigma around those addicted to opioids or substance abuse. Part of that is by talking about the benefits of offering naloxone and test strips to check whether one’s drugs are unknowingly laced with fentanyl.

Carpenter says her reaction to the FDA’s naloxone ruling was excitement because Narcan – and eventually other forms of naloxone – should become much more available for people to purchase. While it changes some of the training she’ll do with pharmacists, it ultimately could decrease the stigma felt by opioid-dependent people seeking resources to be safer.

“The big thing that’s happening with this over-the-counter switch” she says, “is that people will be able to get naloxone at gas stations, convenience stores, pharmacies can move it out [from behind] the counter.”

Tiffany Hall, the clinical coordinator for Orange County’s Street Outreach Harm Reduction And Deflection program, says this could make a difference locally. The outreach team, nicknamed SOHRAD, was created in October 2020 to help unsheltered community members and prevent them from ending up in the criminal justice system based on health needs.

“The gist for us is that we’re located right here on Franklin Street and we can come out to meet them where they are instead of having to go to a service provider,” says Hall. “My role as a clinical coordinator is to link them to mental health or substance abuse services, and also do assessments or some therapy while we’re connecting them.”

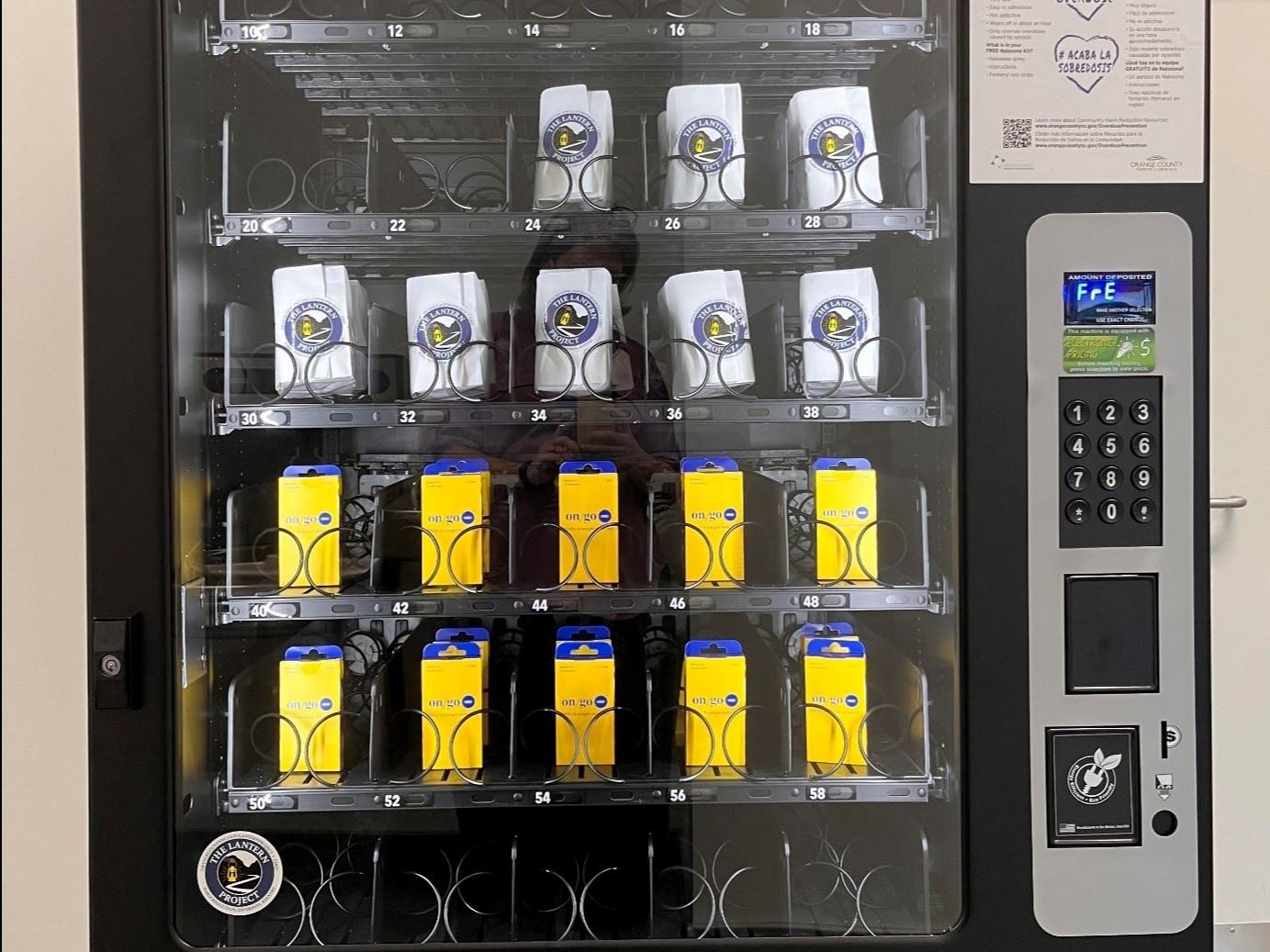

Hall says the SOHRAD team has not yet administered Narcan while on a call, but they are no strangers to the tool to stop overdoses. Similar to the two vending machines with free Narcan kits in Orange County, the program’s peer navigators and leadership regularly offer naloxone spray to the unsheltered community.

“At first, I think there was stigma [by those who were unsheltered] of actually asking for it and knowing that we have it,” says Hall. “And finally, once they realized, ‘Oh, okay, we can just ask for it,’ some readily take it and some we know may need it, we’ll just give it to them.”

The Lantern Project, which is a criminal justice resource department in Orange County, established vending machines with free Narcan kits and fentanyl test strips. They can be found at the Orange County Detention Center and the Southern Human Services Center. (Photo via Orange County.)

Carpenter is quick to caution that the prevalence of more Narcan is not going simply solve overdoses, particularly with the presence of fentanyl. She also says there’s a chance that drug companies could set a high price on over-the-counter naloxone and it could become less covered by Medicaid than it currently is.

“Cost is the big unknown right now,” says Carpenter. Even if it’s available at gas stations, if the price point is out of a lot of people’s reach, then it doesn’t really increase access.”

What can Orange County residents do to help people stay safe or feel less judged? Carpenter says it’s as simple as buying some naloxone spray once it becomes available and getting more familiar about what it can do.

“One of the best things that you could do to reduce stigma,” she says, “is to go out and purchase naloxone yourself, have it on-hand and available in case there’s an emergency, and let other people know you’re carrying it. That creates a social norm around carrying naloxone: if you know a lot of other people that are doing it, it [becomes] something people do to stay safe and potentially help other people.”

Hall says there is one key sector of the Orange County community already trying to do that.

“Some businesses have been asking about it or wanting it, and some businesses do have some on hand right now,” she says. “I know that that’s one of the good things [that this ruling could do]: someone sees it in an establishment, since some of these unsheltered folks frequent some of these businesses.”

For more harm reduction resources in Orange County, visit the county government’s website.

Photo via AP Photo/Matt Rourke.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.