Duke recently held a panel to discuss medical and legal fallout from the U.S. Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Panelists included: Dr. Beverly Gray and Dr. Jonas Swartz who both work as obstetricians and gynecologists as well as Neil Siegel a professor of law and the director of Duke Law’s Summer Institute on Law and Policy.

Below is some of what the panelists discussed.

What’s your reaction as a human being and as a provider of reproductive healthcare?

Dr. Beverly Gray: I think our community was definitely shocked and saddened on Friday, even though we were expecting this news. As a physician who provides abortion care as part of comprehensive obstetrics and gynecology care, I hold my patient stories very close to my heart, and I’ve seen how access to abortion care can save lives. Abortion is common and my family is like many families in the U.S. who know or love someone who has had an abortion. Back in the early 1970s, my grandmother was diagnosed with an unplanned pregnancy and cervical cancer. During the Pre-Roe era, North Carolina was one of a handful of more progressive states, including California and Colorado and those states allowed access to abortion, certain cases, including rape, incest or maternal health risk.

My grandmother underwent a gravid hysterectomy, which removed her pregnancy, her uterus, her cervix, and the cervical cancer that was threatening her survival and abortion saved her life. Like most people seeking abortion today, my grandmother was already a mother. She was poor and access to contraception was challenging in the late 1960s. She didn’t have a high school diploma, but she worked hard in a second shift factory job to provide for her family. She had a great sense of humor. She had an infectious laugh and she was a woman of strong faith. She loved God and her family very deeply. Because of her abortion, she lived to meet her grandchildren. I can tell you that I’m a better person today by having had her in my life.

As an individual obstetrician gynecologist, I provide abortion care for patients facing a variety of life circumstances. Some are like my grandmother managing a life threatening diagnosis. Some have strongly desired pregnancies with diagnoses of birth defects, but many patients are simply seeking autonomy over their lives and their health and pregnancy is not part of what they envision for their future. While I will never meet the physician that cared for my grandmother and saved her life, I’m grateful for the care they provided. I worry right now that at some point in the future, I will be hindered from saving lives like my grandmothers

I think there are a lot of feelings right now. We started our new intern orientation today for our new OBGYNs pursuing this amazing field of medicine. There were a lot of uncertainties around what their training will look like.

Jonas Swartz: I was prepared for it and it still was quite a gut punch. Before Friday we lived in a country where this right was a component, part of the fabric of our nation and one of the rights that we could count on. People could make their own reproductive choices and help them live their lives in the productive way that they chose. It makes me really sad that people are losing that choice.

The reason that I went into OBGYN was that I enjoyed sharing these moments of great happiness and also supporting people in moments of great sadness. It’s an amazing career where you get to participate in a spectrum of emotions and a spectrum of medical experiences with people. Doing abortion care for that reason is really affirming care. You are able to sit down with someone, help them come to a decision that’s right for their life. Providing either medication abortion with pills or providing a procedural abortion, you can in 5 to 15 minutes, help them achieve something that they want to in the future, help them treat a medical problem. That is really gratifying. It’s an honor to be involved in people’s lives like that. When I think about my colleagues across the country who share my passion for reproductive healthcare and now live in states where that care is illegal, I feel sad for them and more importantly, feel sad for their patients that now they have to jump through so many hurdles to get that.

Are there potential legal consequences for women who cross state lines to get an abortion or for people who help them?

Neil Siegel: We’ve been hearing for a very long time now that those who oppose abortion, that they’re not anti-women. It is absolutely heartbreaking that we’re gonna find out what that means. The restrictions that are gonna be imposed, the invasions of bodily integrity that we’re about to endure, what it means, for the state to coerce childbirth. There are [going to] be states that seek to prohibit not just abortion within their own borders, but prohibit residents of their states from traveling out of state to obtain an abortion, and then to return home, as well as those who help them, financially or otherwise, to do that. This is not a crystal clear legal landscape.

One would have to go back to the days of slavery to get the closest legal analogy I can think about in which you have a country deeply divided over a moral question and states are trying to regulate conduct that happens not just within their borders, but outside of it. I’m not saying the abortion debate is just like the slavery debate, but these are not normal legal times. This does not happen very often that you have states trying to regulate conduct that takes place outside their own jurisdictions.

I can tell you that the Supreme Court has protected what’s called “the right to travel.” It’s not mentioned in the constitution. It’s unenumerated, like the right to abortion that the court has now said no longer exists. But the court has protected it going back to 1849. There are various components of the right to travel. The one that’s most relevant to to pregnant people who are seeking reproductive healthcare out of state because they can’t get it in their own state is the right to enter and leave other states. I expect there are five votes on the Supreme Court for the proposition that states cannot prohibit their residents from going out of state to obtain an abortion.

As a practical matter I think it would be extremely difficult in most circumstances, although not necessarily all, for a state to go about enforcing such a ban, given that the sister state that allows access to abortion is not [going to] be cooperating with any kind of criminal law enforcement. Now, having said that, doctors who help patients travel out of state to obtain abortions, who’s in charge of the medical licensing boards within the state that bans abortion, what kind of rules are they imposing? What kind of restrictions are they imposing on doctors? I think that’s something, that physicians are gonna need to look out for in the, the days and months and years ahead.

What is the effect of this decision on your profession? What is the kind of shock to your profession that this ruling has brought about in at least in the short term?

Gray: It’s a topic of conversation [about] how we respond [and] how we move forward. I think the system in which abortion care in this country was possible, even with Roe in place, was problematic. We could see huge disparities based on what state you lived in and the type of care you could access or whether or not you had, insurance coverage to pay for that care. I think people have already been dealing with these problems practically. I worry about how this will impact who will go into this field of medicine. Will we be prosecuted for providing the care that’s right for a patient? If we have a patient and we live in a state where we can’t provide emergency care and we help them seek emergency care in another state, could we be prosecuted?

These are real questions that may come up sooner rather than later. 10 years ago, when I became an OBGYN and finished residency, could I have ever imagined a day that, Roe would not be in place? No. We have a lot of reasons to say these are unprecedented times, but absolutely this is unprecedented for medical trainees. I’m hoping that medical students who are fired up about this issue that wanna protect reproductive health rights will be inspired to join the field.

I do worry that it will impact the number of people pursuing OBGYN in general, the number of people that will apply to our program being in a state where right now we have the ability to provide care. But, what will happen after the next governor’s election, after the next legislative elections, there’s just a lot of uncertainty. I think we’re all in crisis mode right now, trying to figure out how we move forward, how we’re able to provide the care that’s safe and, and right for patients.

What are some medical risks to women in places where safe and legal abortion is no longer available?

Swartz: I think one of the most challenging circumstances is these cases of medical emergency or medically indicated abortion. We very commonly, see people in our clinics who have some medical condition. That means that abortion is safer for them than carrying the pregnancy to term. Overall abortion is really safe and abortion is safer than childbirth. But for these people, it is particularly risky to carry on with a pregnancy. In many cases it can be a sad situation for them [because] this can be a highly desired pregnancy, which they’re terminating for their own health.

What degree of medical risk is enough that you decide that it is a medical emergency? What do you define as a threat to maternal life? Is it a 1% risk of death? Is it a 30% risk of death? Is it a 50% risk of death? Do you have to wait for someone to be actively dying, actively having their organs shut down or have a life threatening infection but if you can intervene or if you suspect that those things would happen, can you intervene before that? I think we are trained to provide evidence-based medical care and this is the only circumstance where I can think of that states are taking away our ability to provide best evidence-based care. We know how to care for these patients and we know how to help them make decisions that are best for their lives and for their health. We’re put in a precarious circumstance.

Our hands are tied. We’re not able to either provide the counseling or more importantly, provide the care that’s life saving. People will seek abortion and get abortions, even if it is illegal in their state. Some people will be able to obtain abortions through safe means by traveling to other states. They may be able to safely order medication pills that are the same pills that we would use if we were performing a medication abortion. They may be able to get an online consultation to do medicated abortion remotely. But other people will resort to unsafe means for abortion. That means that we are going to be seeing more people in our emergency departments or in our clinics who have, incomplete abortions or infections and, may have complications related to that. I think we’re really putting women’s lives in peril or pregnant people’s lives in peril by taking away this right.

North Carolina is one of relatively few Southeastern states where abortion remains legal. Do you expect a big influx of people crossing state line to get abortion and, and do we have the medical infrastructure to be able to, to handle that?

Gray: I think we are anticipating that volumes will increase. We’ve already seen that volumes have increased over these past few months as more restrictive bands have been put in place in states like Texas and Oklahoma, there is sort of this tidal wave effect of patients in those states going to nearby states. In those nearby states, there are delays in care because all the appointments are taken from folks outta state. We are anticipating that there will be an increase in need for patients in the Southeast. We’re worried that in South Carolina that they’re moving quickly to enact a more restrictive ban and those patients will be needing care. We’re already thinking about this.

We have been thinking about this for a few months and how we can expand the care that we offer so that we can be positioned to provide healthcare for the patients that need it. Obviously, our priority is caring for the people in our community and the people in our state, but we want to help as many people as we can. We know that abortion is life saving, is life altering and restricting access forces people to continue their pregnancies to delivery leaving them facing the health risk of pregnancy and barriers to abortion exacerbate the disparities that already exist in our country. Barriers that limit abortion access, disproportionately affect communities of color. We know that in our country, Black women are already facing a more maternal mortality rate. That’s three times higher than that of white women. When we limit access to abortion, we force people to carry pregnancies to term and face those risks. If we can expand access and provide care, that’s the right thing to do.

Could HIPAA protect those who defy state anti-abortion laws. Can HIPAA be affected by last week’s ruling and could it be strengthened to protect patients and providers?

Siegel: Well, I’m thinking specifically about the context of you have a pregnant person who travels interstate to obtain reproductive healthcare because their home state doesn’t allow it. It’s brought to the attention of a local prosecutor who wants to prosecute the individual for violating, hypothesizing now, with state law prohibiting the interstate travel for purposes of obtaining and abortion, or for aiding and abetting, to use legal language, the procurement of an abortion. As a practical matter, I think those prosecutions would be very difficult in most cases to pull off because of a lack of evidence. The prosecutor could ask the doctor’s office or the state in which the abortion occurred for relevant evidence or documentation.

I don’t imagine states that continue to provide access to reproductive healthcare are gonna cooperate, nor would they be required to. I could see HIPAA protecting the medical privacy of the patient who obtained the abortion. It does provide a substantial federal protection for medical privacy. I would imagine, although I don’t know, that it could be strengthened even more. I don’t see that happening in Congress without the termination of the Senate filibuster as to legislation given disagreements about abortion between the two parties in Congress. I would expect again without being a HIPAA expert that medical privacy, as well as the refusal to cooperate of sister states that provide access to reproductive healthcare, would provide a lot of legal and practical protection, to people who do travel interstate to obtain an abortion.

Some states with abortion bans make exceptions when there is risk to the life of the mother. What are the immediate risks to the life of the mother and how does that complicates the ability to provide care?

Gray: I think it’s it’s hard enough to to do our job some days, but then to have to decide is this patient’s life at risk enough for me to care for them? Am I going to put myself at risk to care for a patient? There’s so many shades of gray in medicine, and we know that pregnancy is riskier than an abortion just in general and forcing people to continue pregnancy is that risky enough for their health? I think some people would say yes, other people would say it needs to be more of immediate risk. They need to be bleeding to death or severely infected or something needs to be happening. If you’ve made it to that point, it’s really risky.

Even in those cases you’re not guaranteed that you’re gonna save a life if you wait until that patient is at the brink of death. That’s not fair to people either. It’s these shades of gray where a lot of people think, well, you know, a 20 week ban that sounds reasonable. But at 20 weeks a patient might just be developing enough impacts from their heart disease or their cardiomyopathy or their other underlying medical issues that are causing them to have organ failure that are causing them to need to be in the ICU to stay alive. By simplifying it say, “Okay, we’ll make a 20 week ban,” there are all those patients that fall into that window where it’s very difficult to make the determination of when is the risk enough. We just need to be providing evidence-based care to our patients, but instead we’re forced to learn the law in ways that I never would’ve anticipated having to learn the law. When I went to medical school, I went to medical school. I did not go to law school. Now I’m having to learn all these new things. Am I [going to] have to call up a lawyer to make a decision for a patient? That just seems like an extra step that puts people’s lives at risk.

What are the problems with a 20 week ban on abortion from a provider standpoint?

Swartz: The vast majority of abortion occurs in the first trimester. 90% of abortion care is in the first eight weeks of pregnancy. Abortion becomes increasingly rare as we go along in gestational age. One circumstance are these medical circumstances where people need an abortion. There already is a carve out in the law that would allow us to intervene there. The other circumstance that we commonly see is people who have a fetal condition that is diagnosed at that point in pregnancy that needs to be treated. Before the 20 week ban was enjoined, that meant that people would get their anatomy ultrasound, which is often a very happy occasion. The doctors would see some anomaly or some change, and the couple would immediately have to make a decision about whether they wanted to move over with termination because the clock was ticking.

You’re putting families that are already in this very difficult and devastating situation now in this falsely imposed time pressure. There’s nothing special about 20 weeks in terms of development of fetus. There’s no special function that has been discovered about, uh, the sort of fetal wellbeing at that time. Abortion does not cause pain to fetus. A fetus can’t feel pain prior to 28 weeks. This is just an arbitrarily designated state imposed risk that was historically imposed. We really need to, to provide full spectrum care to people. We need to have that option. Reinstating that ban, which I understand why it’s likely that it will happen, I strongly oppose it. It’s why my colleagues challenged that law because it was so important for us to be able to provide care in those circumstances and not have people have to leave the state to get that care. We have some experience with people needing to lead the state to get care and it’s really limiting, it’s really inconvenient. It really puts a tremendous burden on people. This sort of undue burden standard is no longer where we’re looking in the real world. Putting that burden on people is, is horrible.

How do restrictions on abortion tend to enhance healthcare inequities for people of color and broaden the gap in access to reproductive healthcare more generally?

Gray: We talked a little bit earlier about how in our country, right now we have a maternal mortality crisis. If you’re a Black woman in this country, your risk of death during pregnancy is three times higher than white women. We are struggling with how we help patients reduce risk during pregnancy and how do we combat the racism that exists in our system at all levels to improve maternal healthcare. Patients who are facing a pregnancy and know that their life is at greater risk, may make the decision to end their pregnancy. I think every single person that we care for is an expert in their own lives. People don’t understand kind of what people are facing, the challenges that they’re facing. Whether they’re financial challenges, more than half of people seeking an abortion already have kids that they wanna be around to take care of that they want to live for.

We have to respect the expertise of the patients that are seeking care. I think there’s been a lot of sadness and distress around this ruling, but I think there are also some areas of hope. There are communities that can be the experts in how we restructure, how we provide care in this country. That gives me hope that there are people out there that are experts in their lives that can, that can help us create solutions that impact the people that need them the most. I think we’ve cobbled together this system relying on Roe and now we’re facing a different challenge and we just need different tools, different experts. We need the communities that are impacted the most to be at the table. We need to listen to stories of people who have had abortions because I think what happens is that we talk about this in the abstract and we forget the humanity, the lives that are impacted every single day of people that we’re caring for. Until that can be unveiled, until the shame and stigma around abortion can be unveiled and people can really have an understanding, we’re gonna continue to struggle. I try to be an optimist and I’m hopeful that through all of this, through this horrible ruling, through the worsening of these disparities, that we’re gonna come out of this with something better, we have to. That is the right thing to do.

Would you expect in the court system to see challenges to those state, the various state laws under under particular small conditions here and there in the same way that the conservative movement challenged laws that allowed abortion?

Siegel: I certainly do expect a lot of litigation. I mentioned the right to travel, which can be invoked for those who travel interstate. I mentioned the possibility of a preemption argument for the interstate shipment of abortion inducing medication. A third possible legal theory that is implicit in much of our conversation today is what’s called vagueness challenges. The due process clauses of the constitution protect people against vague laws, especially vague criminal laws. If you have a statute that talks about an immediate risk to the life of the pregnant person, as the doctors have asked today, what exactly does that mean? Or impairment of a major bodily function? What exactly does that mean? I think the language of these statutes and the guidance that is offered by the states is [going to] matter a lot because it would not surprise me if a number of federal courts were to decide that a number of these laws were unconstitutional [or] vague. You can’t pass a vague statute, vaguely broadly, banning abortion with some exceptions that are not particularly defined.

Doctors are forced to spin the wheel and we’ll see where it lands, whether or not they can be prosecuted. American law doesn’t work that way anymore. I would expect those kinds of vagueness due process challenges to endure. My bottom line point is that the future of reproductive healthcare in this country lies in politics, not in law. If you get the politics right, the law will take care of itself. This has been a conservative political movement for decades that has succeeded in a bunch of historically contingent ways in changing the law, through winning enough elections in the White House and the Senate to produce a five justice majority that was willing to do what the court just did in Dobbs. I think politics and voting and mobilization is really where those who believe in the vital importance of reproductive healthcare need to focus their efforts as doctors and lawyers do the best they can day by day, patient by patient, client by client trying to help people.

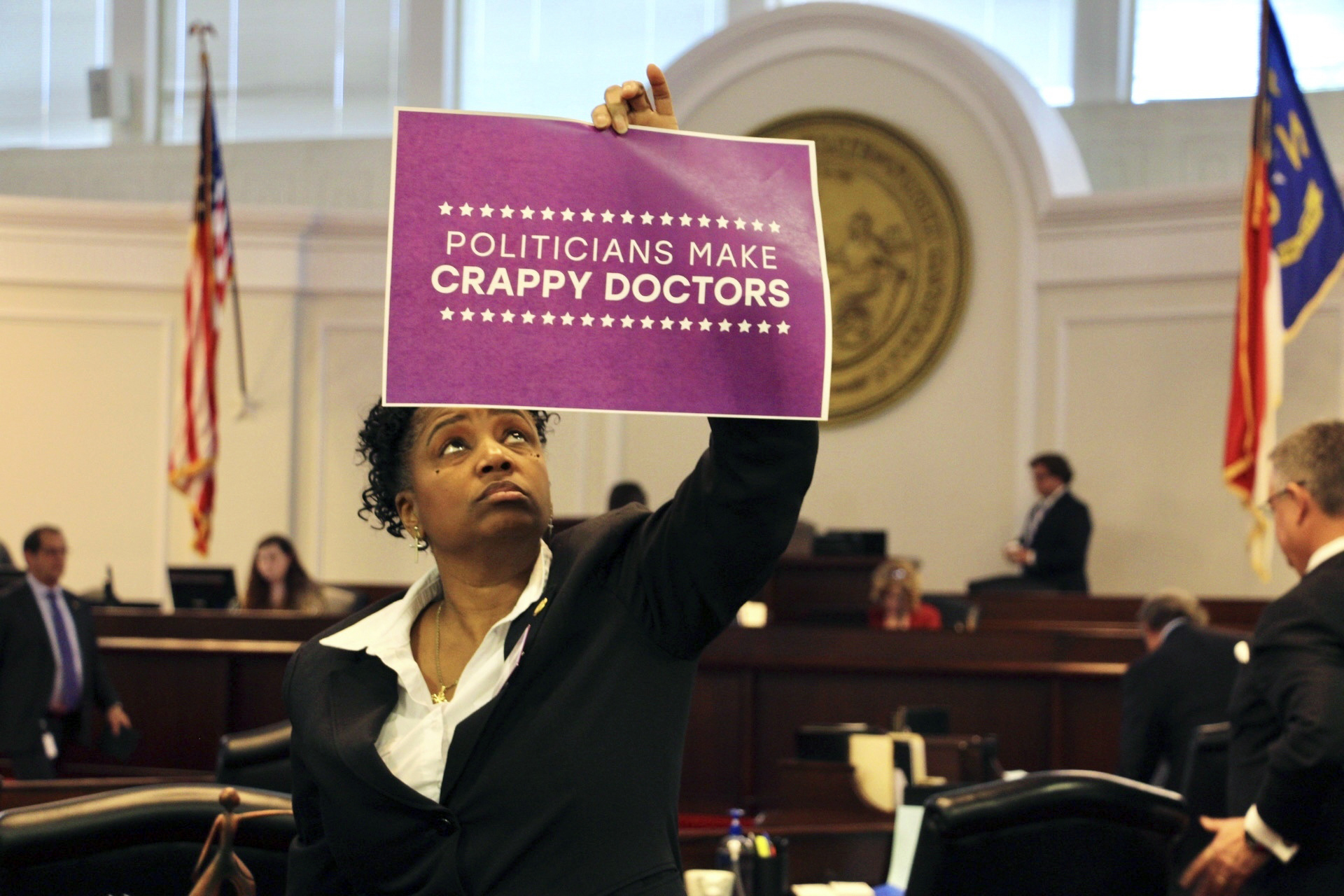

Featured photo via Jacquelyn Martin File/AP

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.