The 110-mile Haw River helps provide drinking water to more than 300,000 people, flowing through eight counties including Orange, Chatham, Alamance, and Durham. In February, the nonprofit working to protect is hosting several opportunities to hear an update on the watershed’s health and the group’s ongoing policy efforts.

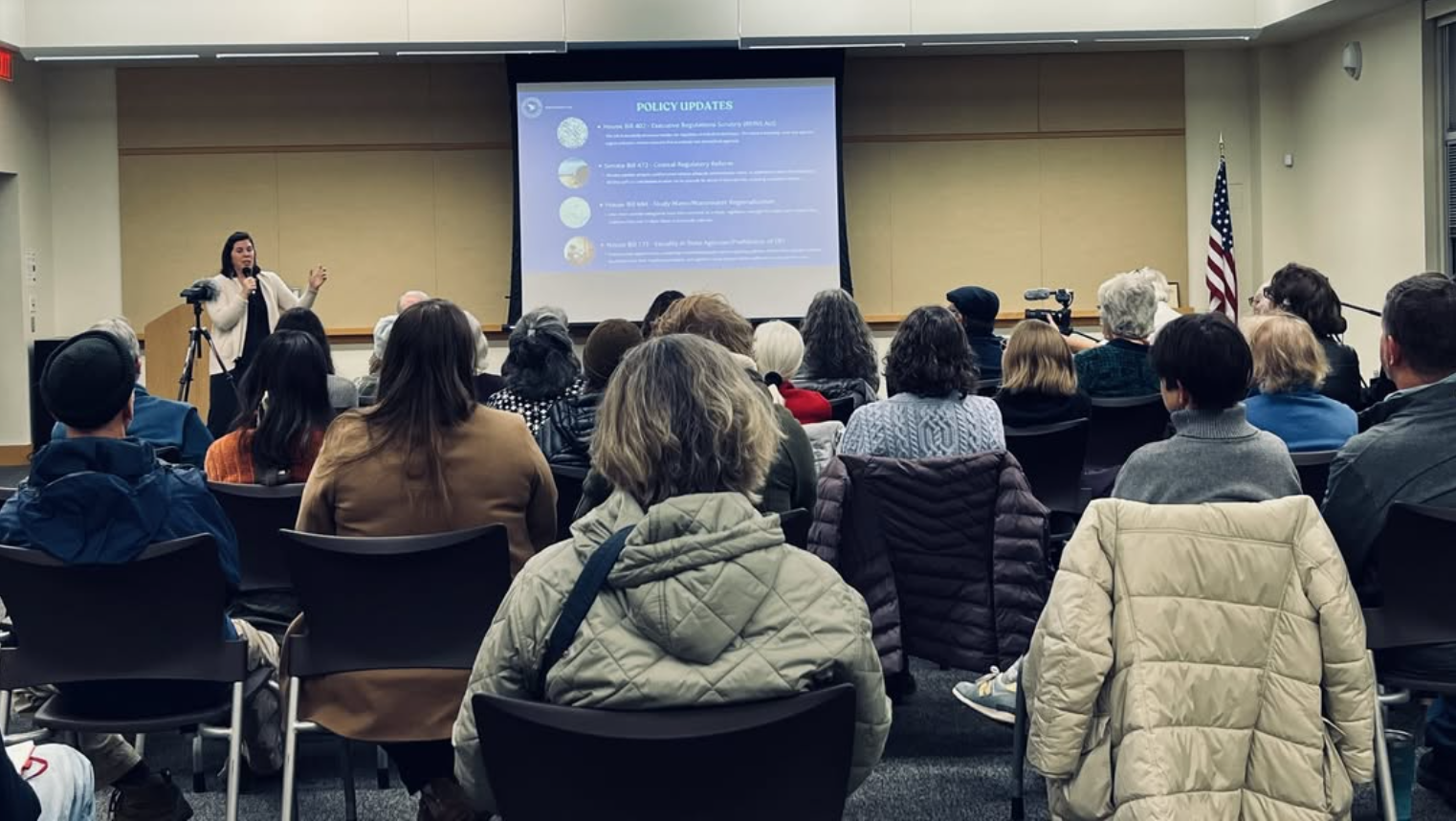

On Jan. 15, a small crowd of local residents and elected officials gathered at the Chatham Community Library to hear the Haw River Assembly’s State of the Haw Report. While it includes various parameters of the river monitored by the nonprofit’s seven-person team — from pollution to cleanups — the presentation particularly focused on policies impacting the watershed and the aftermath of Tropical Storm Chantal.

According to the nonprofit’s Executive Director and River Keeper Emily Sutton, the historic flooding was a major contributor to the Haw’s water-quality issues for 2025. She said the community saw up to 10 inches of water in some locations, costing Orange County alone more than $50 million in combined commercial, public, and residential damages.

“I wanted to make sure that I’ve mentioned those numbers because it’s a lot less costly to have buffers, and green storm water infrastructure, and constructed wetlands,” Sutton said. “And all of these things that would be a meaningful difference to flood resiliency. During this time, we also provided well tests for over 135 community members. Almost 50% of those failed due to E coli and fecal contamination.”

The presentation especially focused on the nonprofit’s work in reducing the watershed’s PFAS and 1,4-dioxane levels, which Sutton said have gone down “considerably” this year as a result of its recent lawsuits. She explained how the “forever-chemicals” have been a longstanding issue for the Haw because treatment plants are not required to treat the wastewater it accepts from industrial users.

That was the case for Burlington’s East wastewater plant, contributing to high levels of PFAS in Pittsboro’s drinking water. In 2019, the nonprofit and the Southern Environmental Law Center jointly sent a letter of intent to sue the city as a result, according to Senior Attorney Jean Zhuang.

“We discovered that [the PFAS] was coming from Burlington’s wastewater treatment plant, which was receiving water from different industries within a sewer system,” Zhuang said. “And then we conducted a long investigation to figure out which of those industries were the source. Because the pollution levels were so high, we knew it had to come from an industry.”

Burlington phased out the three industries responsible for the PFAS production, and describing the case as one of the first of its kind, Zhuang said the partnership showed how cities are capable of controlling that pollution. However, she said they need to start doing the work now, noting how there are several wastewater treatments in the state responsible for industrial chemical pollution.

And while Zhuang said there is now significantly less of the chemical in Pittsboro’s drinking water, she thinks the Haw still has a “long way to go.” For example, Sutton said there is similar work to do in places like Greensboro and Reidsville, and the Haw River Assembly is in active litigation with the City of Asheboro to challenge a permit in an effort to reduce its 1,4-dioxane levels.

The Haw River team also gathered data on nutrient pollution, industrial animal agriculture pollution, sediment pollution, and dissolved oxygen levels, and Sutton explained how the group’s research every year is integral in advocating for policy changes. For example, the nonprofit collected more than 24,000 pieces of trash last year, a majority of which came from Durham’s Third Fork Creek.

“When we think about this amount of data, that’s incredibly helpful for us to go to the City of Durham [and say] last year we picked up 15,000 pieces of trash, 12,000 of those pieces were styrofoam,” Sutton said. “If you passed this common-sense policy to eliminate styrofoam, this would have a meaningful impact on our stream.”

But Sutton stressed how in order to make those differences, the nonprofit needs the community to make more noise, particularly if the federal government continues to pass policies that could be harmful to watersheds like the Haw. One she called “particularly devastating” from the past year is the Reins Act, which could make it more difficult for the EPA to pass water quality standards. The group will be lobbying against it in 2026, and on those days, the river keeper said she wants more people to join the effort.

“I can’t tell you how many times I go into a legislative office and they’re like, ‘That sounds great, Emily, but I’m not hearing from my constituents,’” Sutton said. “It really matters that they’re hearing from the people they represent and not just me.”

Community members of all ages can also get involved with the group year-round through various programs and cleanup opportunities. The Haw River Assembly will also host an open house on February 7 to celebrate more than four decades of work. To learn more click here.

The nonprofit will also share its State of the Haw Report at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro on Feb. 5 and at Alamance Community College on Feb. 19. To register, click here.

Featured image via Haw River Assembly.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.