Written by GARY D. ROBERTSON

Tens of thousands of North Carolina residents convicted of felonies but whose current punishments don’t include prison time can register to vote and cast ballots, a judicial panel declared Monday.

Several civil rights groups and ex-offenders who sued legislative leaders and state officials in 2019 argue the current 1973 law is unconstitutional by denying the right vote to people who have completed their active sentences or received no such sentence, such as people on probation. They said the rules disproportionately affect Black residents and originated from an era of white supremacy in the 19th century.

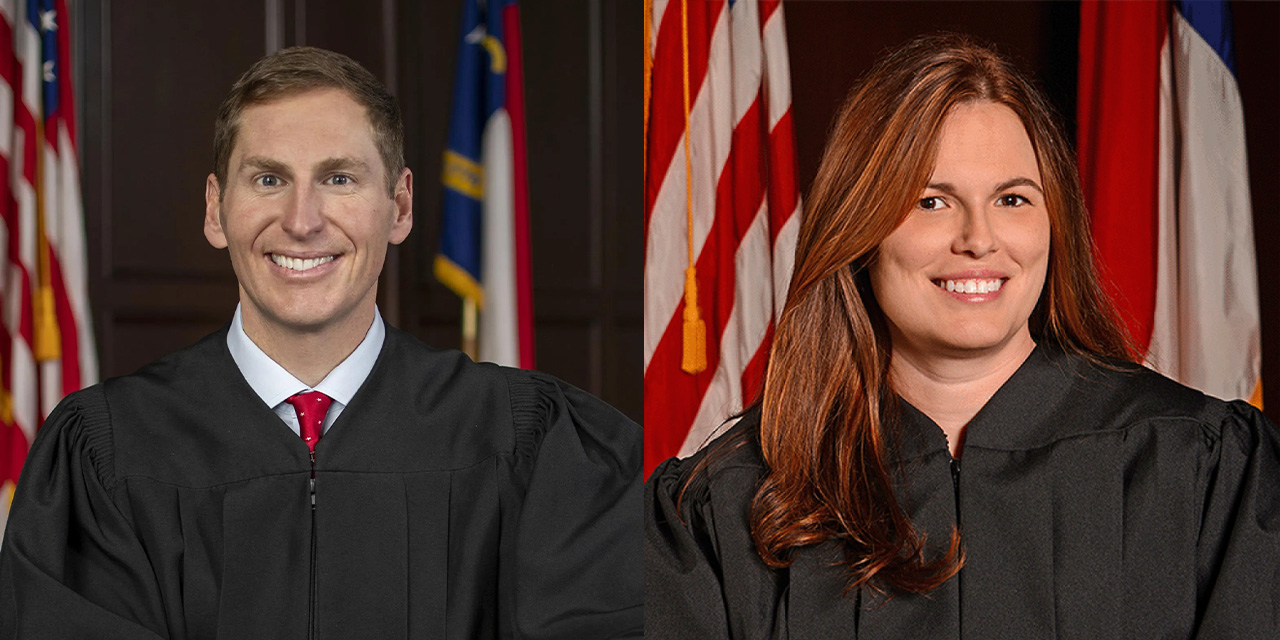

In a brief hearing following a trial last week challenging the state’s voting restrictions upon felons, Superior Court Judge Lisa Bell said two judges on the three-judge panel have agreed they would issue a formal order soon allowing more felony offenders to register. The judges are acting before issuing a final trial ruling, as voting in October municipal elections begins next month.

Roughly 56,000 more people would now be allowed to vote, based on estimates. One lawyer said it represents the largest expansion of North Carolina voting rights since the 1960s.

“When I heard the ruling, I wanted to run in the street and tell everybody that now you have a voice,” said Diana Powell with Justice Served NC, a Raleigh-based community group that sued. “I am so excited for this historic day.”

Current law says felons can register to vote once they complete all aspects of their sentence, including probation and parole. With the upcoming order, felons who only must complete these punishments that have no element of incarceration can register. The decision also would apply to people convicted of a federal felony but whose current punishment is probation.

A lawyer for House Speaker Tim Moore, who is a defendant along with Senate leader Phil Berger and the State Board of Elections, said an appeal to block the panel’s preliminary injunction will be filed.

Moore attorney Sam Hayes called Monday’s decision an “absurd ruling that flies in the face of our constitution and further casts doubt on election integrity in North Carolina.”

The defendants also could appeal any final ruling from the judges that expands restored voting rights moving forward to the 2022 elections, which include a U.S. Senate seat. An uptick in voter rolls stands to affect races in the closely partisan-divided state. There are 7.1 million registered voters in North Carolina.

Last year, the same judges ruled a portion of the law requiring felons to pay all monetary obligations — likes fines and restitution — before voting again was unenforceable because it made voting dependent on one’s financial means. That allowed more people to vote last November.

Now, “if a person can just say, ‘I am not in jail or prison for a felony conviction,’ then that person can register and they can vote freely,” said Stanton Jones, one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Bell, the panel’s chief judge, said Monday that the majority’s reasoning for the injunction would be explained in their order. The state election board said Monday was its deadline to change registration forms for the fall, and that county boards must immediately begin to permit these individuals to register.

Dennis Gaddy, co-founder of Community Success Initiative, a Raleigh-based organization that helps ex-prisoners and another plaintiff, said his group and others would have a statewide registration drive.

“The wait is over, and I’m excited to be a part of this transformation,” said Gaddy, who was once behind bars and unable to vote for seven years after his release because he was on probation.

The North Carolina Constitution forbids a person convicted of a felony from voting “unless that person shall be first restored to the rights of citizenship in the manner prescribed by law.” The 1973 law, approved by a Democratic-controlled General Assembly and written in large part by Black legislators, eased restoration requirements.

A plaintiffs’ witness testified last week that felony disenfranchisement had origins from a Reconstruction-era effort to intentionally prevent Black residents from voting. Now more than 42% of the felony offenders on probation or supervision and who are disenfranchised are Black, according to a court document.

Legislative leaders acknowledged in a legal brief that for much of the state’s history, felony disenfranchisement was used to exclude African Americans from voting. But they said there was no evidence the 1973 law was motivated by discriminatory intent — rather, it treats all offenders the same.

Sen. Warren Daniel of Burke County, a top Republican on election issues, portrayed the upcoming order as judicial overreach: “If a judge prefers a different path to regaining those rights, then he or she should run for the General Assembly and propose that path.”

Twenty states automatically restore voting rights for convicted felons when they are released from prison, while about 15 restore those rights upon completion of their sentence, including probation and parole, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.