Orange County community members gathered in the courthouse Saturday afternoon for a soil collection ceremony of five lynching victims who were killed in 1869. The group honored their memories and mourned their losses in several ways, while also drawing comparisons to current events they deem to be suppression tactics for North Carolina’s Black population.

To help begin the program on Saturday, North Carolina Poet Laureate Jaki Shelton Green recited verses, with additional performances from Chapel Hill Poet Laureate Cortland Gilliam and dancer Jasmine Powell following soon after. Just a few feet away, ten empty jars sat next to five buckets of soil, each with its own hue of the earth. The jars had names etched into them: five local Black men, who were all lynched within months of each other.

Before long, attendants to the ceremony lined up to take turns adding that soil into the jars, slowly filling them up and helping the victims’ names stand out in contrast with the dirt of their lynching sites inside.

Expressionist Jasmine Powell dances during the soil collection ceremony, incorporating the jars into one of her performances.

Washington Morrow, Wright Malone, Daniel Morrow, Thomas Jefferson Morrow and Cyrus Guy each had their lives cut short nearly 154 years ago by white supremacists – whose motives may have differed, but whose intentions of intimidation were the same. Their murders happened in the year between when the North Carolina constitution was amended to allow Black men to vote (1868) and when the Conservative Party first gained control of the state government (1870).

Glenn Hinson is a UNC history professor and one of the members of the Orange County Community Remembrance Coalition, which helped organize Saturday’s event. He added historical context of both Orange County in 1869 and what is known about each of the victims. Hinson said when he learned about the Morrows, Malone and Guy through a UNC project reporting lynching sites across North Carolina, he brought it to the coalition – which was started in 2018 to learn about and honor such victims.

“What we set out to do from there,” he said, “was to discover more – not just about deaths, but about families. How can we learn about what happened to those families, how can we learn about occupations, how can we learn about the history that led to this beforehand?”

What began in March 2022 as five names turned into a deep-dive of old census records, archived newspaper articles, and regular requests to the county’s Clerk of Court. Once more information was collected, the Orange County coalition contacted the Equal Justice Initiative, which runs the National Peace and Justice Memorial in Alabama. In time, the names of the victims and soil will be added to its collection. One jar for each victim will travel to Montgomery to live there, while the coalition will keep a second jar in Orange County.

Paris Miller-Foushee, another member of the remembrance coalition and a Chapel Hill Town Council member, was also a presenter at the ceremony. She said one of the most affecting parts to her while working on the project was envisioning the grief and perseverance of those very families left behind.

“I have a Black daddy, I have a Black husband, I have a Black son – I see myself in the lives lost and what that means,” Miller-Foushee said afterward. “As I was learning about them, [the erasure of the victims] really struck me the most and how we as a community have an opportunity to honor their lives now. And to honor their families, to find the descendants and say, ‘We see you, we hear you, and we’re going to tell this story collectively.’”

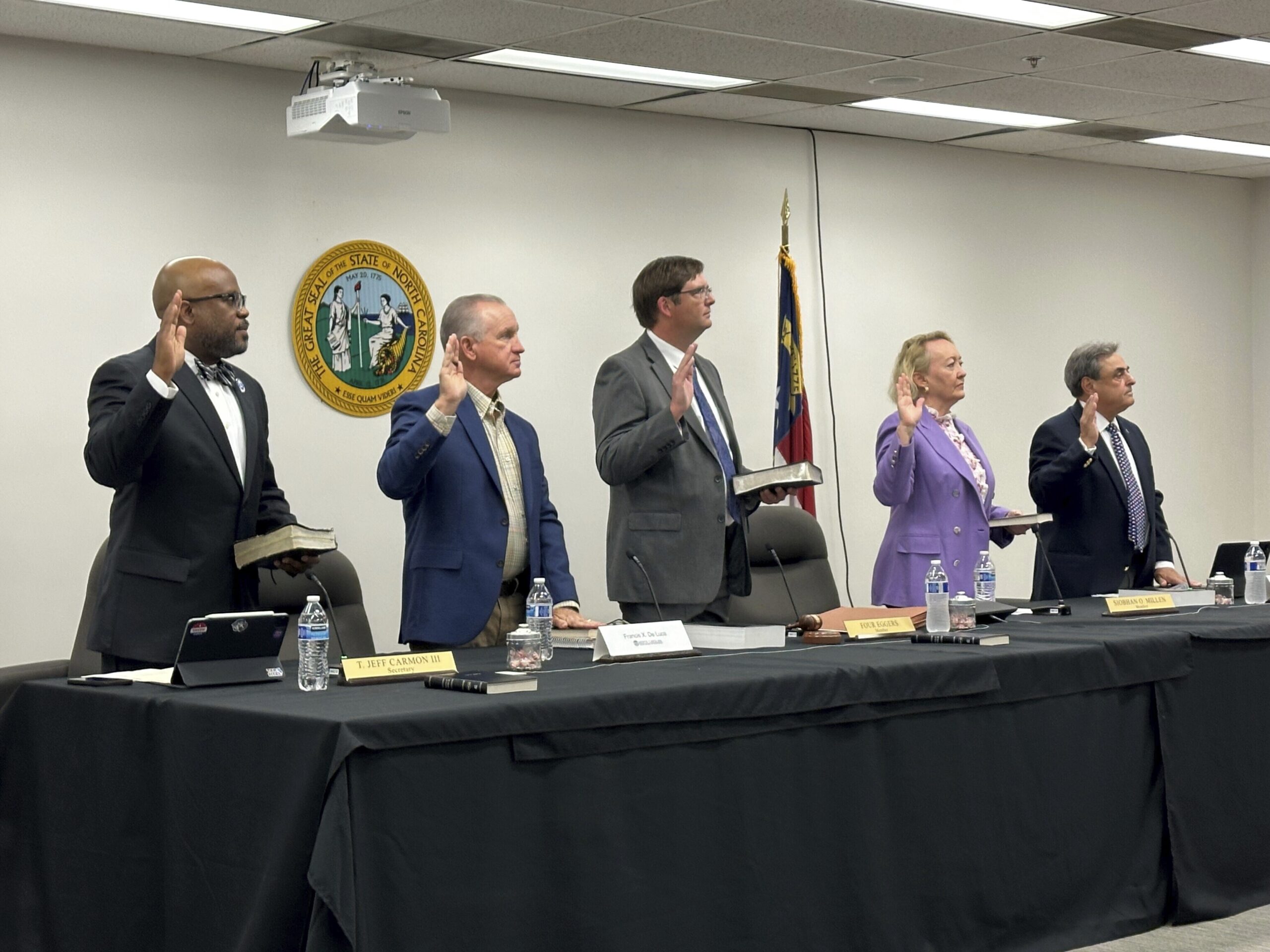

Paris Miller-Foushee (right) and Glenn Hinson of the Orange County Community Remembrance Coalition share backgrounds of five racial lynching victims from 1869.

Some of the ceremony’s speakers also made clear that while the lynchings were decades ago, efforts to oppress or intimidate minority communities are not a thing of the past. Co-chairs for the OCCRC James Williams Jr. and state Rep. Renée Price each shared comments about how recent rulings by North Carolina’s Supreme Court and bills filed in the government reflect efforts to exert control over Black residents’ existence in society.

“We look at felon disenfranchisement, suppressing the vote and making sure Black people in particular can’t vote,” Williams said of the Supreme Court’s rulings. “We have cases related to education, gerrymandering, voter ID – all of these cases are rooted in this past.”

“If you’ve paid any attention to the recent policies, laws, or decisions by the Supreme Court, we have in no way seen the final days of [racial] terror in this country,” added Price.

“The conditions of racial violence, the conditions of supremacists’ actions, those haven’t changed so much,” Hinson said afterward. “This [ceremony] becomes a moment to reflect on the ongoing [actions] and to charge us to step differently into the future.”

OCCRC member Danita Mason-Hogans said while those actions of others may recall tactics of the past, she believes that white supremacy is in its final stages of influence. She said she felt it was equally important to highlight the bravery of Lucinda Morrow – the wife of Thomas Jefferson Morrow and mother of Washington – who testified against suspects in her family’s deaths. Mason-Hogans said it was that aspect of the family’s story that struck her the most.

“Even in the face of terror, the Morrow family made people realize there were humans who were killed and they stood up to authorities,” she said. “I see them, of course, as victims but I see them in a huge way as an [inspiration] of a spirit of resistance that has always also existed here. I think we need to do more telling those stories too, because it’s not just about oppression, it’s about people’s response to that oppression.”

One of the Morrows’ relatives spoke during the ceremony: Durham resident Krishna Mayfield, who’s a descendant of the Whitted-Browder family. She told the crowd that while no one in the family had forgotten the three members killed in 1869, they’re appreciative that the trio is being more widely recognized.

But, similar to Mason-Hogans, Mayfield urged the crowd to not let the end of Washington, Daniel and Jefferson’s lives define how they’re remembered. She said she believes it’s important to consider that whether someone had a tragic ending or is remembered as a hero, there are dozens of other community members through the years who had critical impacts on Orange County.

“At the end of the day, we are human beings just like everyone else,” said Mayfield. “We have pride in our history and our accomplishments, we have helped to build this country since the very beginning. If you drive anywhere in this area, you will see our [local] contributions.

“Thank you for coming,” she added, “but I just ask that you do not forget us and that you recognize our family.”

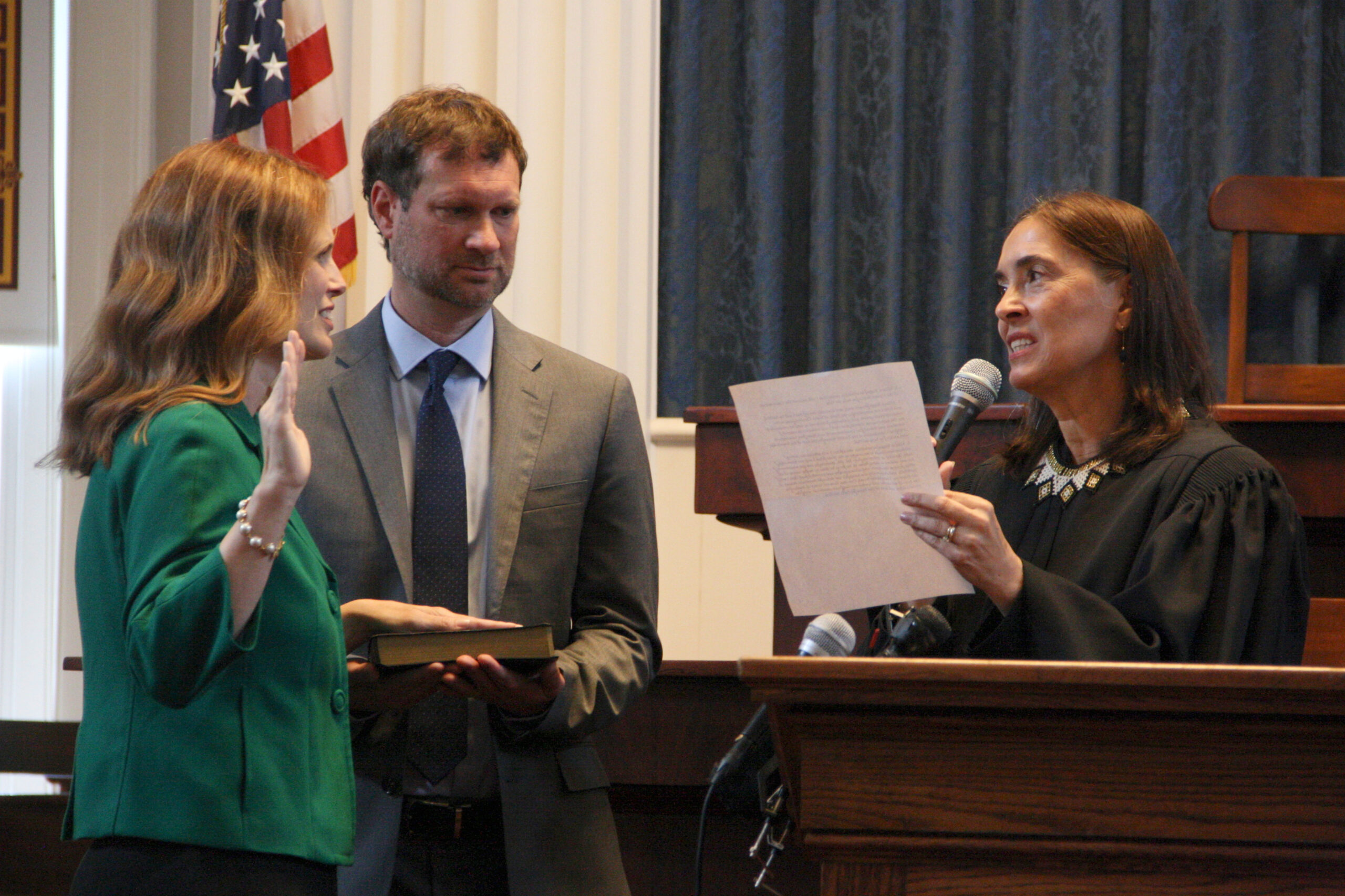

Krishna Mayfield, a distant relative of the murdered Morrows, speaks to the crowd before soil from where the victims were lynched is put into jars.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.