Pirates in North Carolina again?

Yes, we remember Black Beard. Most authorities now agree that the shipwreck we thought was Black Beard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge is just that. The big news about the recovery of the ship’s anchor has us talking about pirates again.

The new “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie, although not as big a hit as its predecessors, brought the world’s attention to pirate mythology again.

At East Carolina University, the Pirates nickname for its athletic teams makes all ECU fans justifiably proud of their pirate heritage. It is the same thing for many North Carolina high schools that have adopted this popular nickname.

But, when we are pushed to explain why we are so enthusiastically romantic about pirates and their mythology, we begin to stutter. It is difficult to explain why we would want to tie ourselves so closely to a group of ruthless, brutal, selfish thieves. These are not the kinds of people we ordinarily would claim for our own.

We simply do not have a good explanation for our love of pirates.

Three new books might help us as we struggle to understand our identification with pirates.

First, there is “Sir Walter Raleigh: In Life & Legend,” a biography by Mark Nicholls and Penry Williams. As noted in an earlier column, this book teaches us that Sir Walter’s colonizing efforts on our coast were originally intended to be used as a big base to support the business of capturing Spanish ships carrying South American gold to Spain. Queen Elizabeth authorized and encouraged such privateering. But there was a thin line between privateering and piracy. So you could say, and not be far from the mark, that North Carolina’s close association with pirates began with the earliest European contact with our land.

Second, “The Jefferson Key,” a thriller by Steve Berry and already a New York Times bestseller, is based on the premise that privateers helped win the Revolutionary War for George Washington by disrupting British commercial shipping. That is at least partially true.

In the book, which is fiction, Washington was so grateful for the service of the privateers that he gave several North Carolina families the right to attack and seize the commerce of America’s enemies in perpetuity. These fictional families, led by a complicated man named Quentin Hale, live on posh estates near Bath.

Even more disturbing, when Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, and Kennedy tried to limit their perpetual authority to engage in privateering, these North Carolina families arranged for their assassinations.

Thirdly, Michael Parker’s novel, “The Watery Part of the World,” set on the Outer Banks, opens in 1812 when a group of land-based North Carolina pirates seize a grounded schooner carrying Theodosia Burr Alston, daughter of former Vice President Aaron Burr and wife of the governor of South Carolina.

In this story, the pirates butcher most of the crew and passengers. Theodosia survives only to find herself in a community of pirates run by a terroristic dictator. Without apology, these thieves draw to the shore where they will run aground. They attach a lantern to the neck of an old horse and walk it up and down the beach. At night the bobbing light looks like another ship sailing in a safe area. Nags Head gets its name from this activity.

Michael Parker’s fictional land-based pirates on the Outer Banks are as evil and brutal a bunch as you could ever imagine. His book is a wonderful read and a great adventure story. But I hope that the cruelty of our pirate forebears on the Outer Banks is exaggerated.

Put on your eye patches, wear those funny hats, and hold on to your plastic swords – we North Carolinians are going to be pirates to the end.

Related Stories

‹

![]()

Bookwatch returns with authors who were worth waiting forThose who missed North Carolina Bookwatch on UNC-TV while it has been off the air to make room for “Festival’s” special programming can look forward to this Sunday afternoon at five o’clock. Bookwatch returns with an encore lineup of books, authors, and characters. It all begins next Sunday with Rachel, the blue-eyed child of a […]

![]()

New books and a new BookwatchUNC-TV’s North Carolina Bookwatch begins a new season on Friday, August 5, at 9:30 p.m., and Sunday, August 7, at 5 p.m. My editors let me share with you my reading suggestions. They know that the suggestions parallel exactly upcoming Bookwatch shows. Because earlier columns have already discussed several books on the list, […]

Duke Energy Seeks to Merge Carolina Utilities, Projecting More Than $1B in Customer SavingsDuke Energy Corp. said it formally asked federal and state regulators on Thursday for permission to join together its two subsidiaries.

How Helene Became the Near-Perfect Storm To Bring Widespread Destruction Across the SouthHurricane Helene killed and destroyed far and wide — from Tampa to Atlanta to Asheville, North Carolina, its high winds, heavy rains and sheer size created a perfect mix for devastation.

Duke Energy Prefers Meeting North Carolina Carbon Target by 2035. But Regulators Have Final SayWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON Duke Energy Corp. offered Tuesday updated proposals on how it would meet mandated greenhouse gas emissions reductions in North Carolina through increasing solar and wind power generation and replacing outgoing coal-fired plants in part with new nuclear and hydrogen technologies. A landmark 2021 law directed the North Carolina Utilities Commission to create an ongoing […]

North Carolina GOP Overrides Veto of 12-Week Abortion Limit, Allowing It to Become LawWritten by HANNAH SCHOENBAUM, GARY D. ROBERTSON and DENISE LAVOIE Legislation banning most abortions after 12 weeks of pregnancy will become law in North Carolina after the state’s Republican-controlled General Assembly successfully overrode the Democratic governor’s veto late Tuesday. The House completed the second and final part of the override vote Tuesday night after a […]

Republicans Take to Mask Wars as Virus Surges in Red StatesWritten by WILL WEISSERT Top Republicans are battling school districts in their own states’ urban, heavily Democratic areas over whether students should be required to mask up as they head back to school — reigniting ideological divides over mandates even as the latest coronavirus surge ravages the reddest, most unvaccinated parts of the nation. Republican Gov. […]

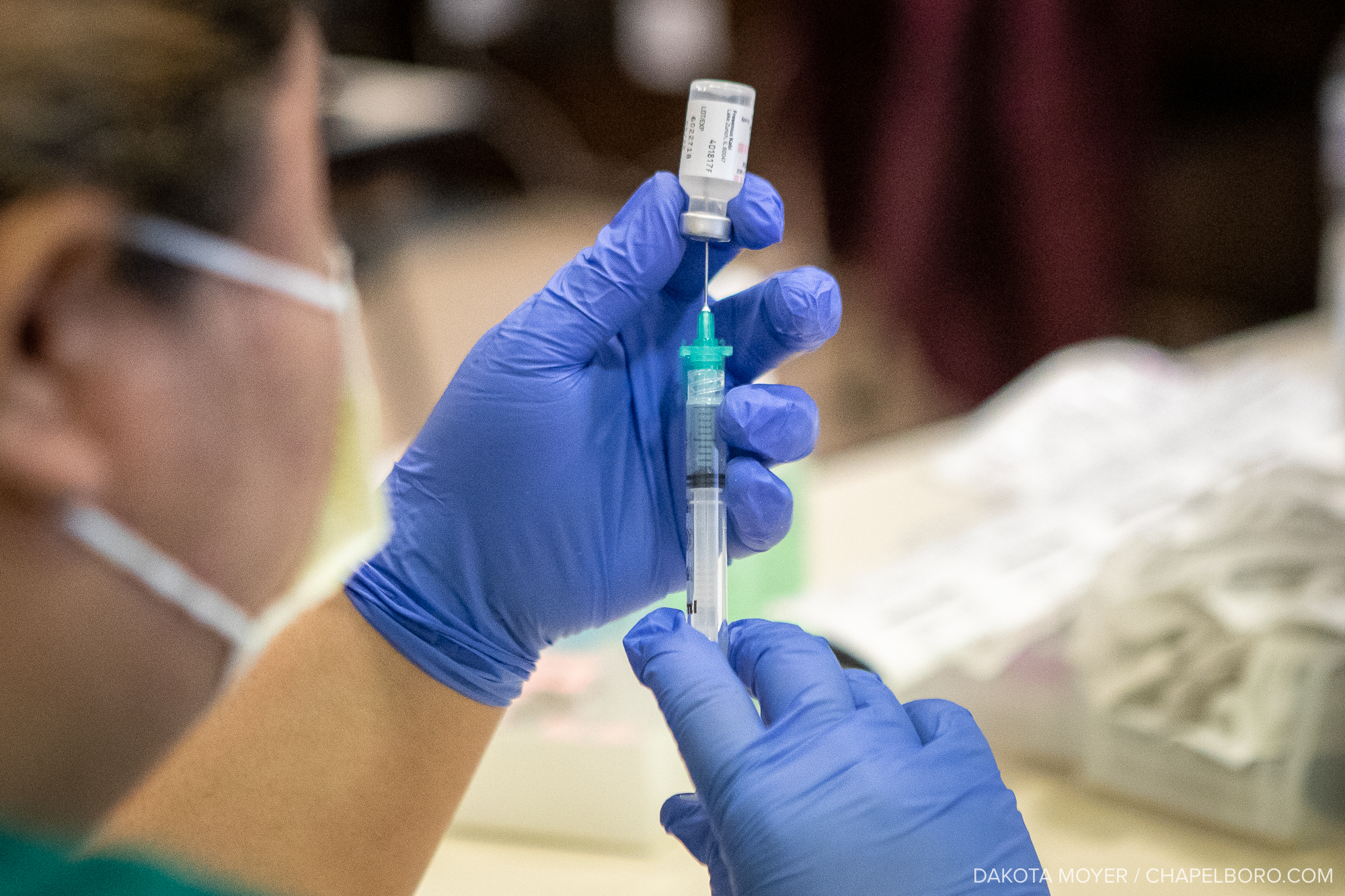

North Carolina Moves To Limit Out-of-State Access To VaccineNorth Carolina is shifting its vaccine distribution guidance to dissuade people from traveling long distances to receive a COVID-19 shot in the state. Under updated guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clarifying travel policies, North Carolina has enacted stricter vaccination policies to improve North Carolinians’ access to the vaccine. “To promote the […]

![]()

4th Time in 4 years: It's Hurricane Evacuation Time in USIt’s become a hurricane-season ritual in the Southeast: When a storm threatens, coastal residents board up homes, load up SUVs and fill highways where the traffic lanes are reversed to offer a speedy escape inland. For some people, Hurricane Dorian is the fourth storm they have had to flee in four years. Forecasters are not […]

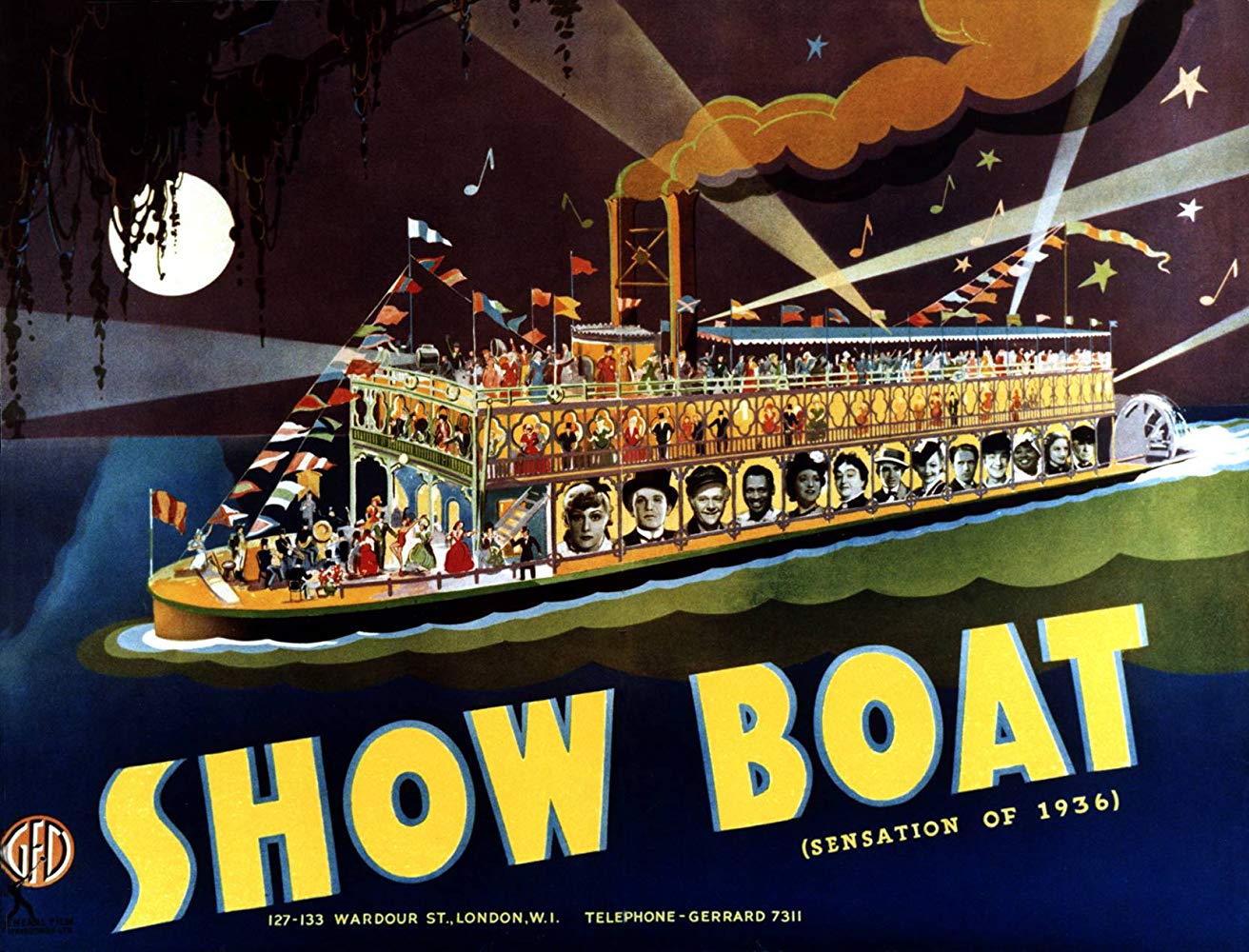

Local Lore: Blackbeard and Show BoatsIn eastern North Carolina, Beaufort County in particular, you’ll find the small town of Bath. Measuring just under a square mile and home to just 249 people as of the 2010 census, Bath is an unassuming little hamlet that proudly holds the title of “North Carolina’s Oldest Town.” Incorporated in 1705, Bath is home to […]

›