A memorial was held on Friday afternoon for William B. Aycock. Aycock served as Chancellor at UNC from 1957 – 1964 and was a faculty member at the School of Law before and after his time as Chancellor. Overall, Aycock served the University of North Carolina for nearly 40 years, from his first faculty appointment at the school of law in 1948 until his retirement in 1985.

Gene Nichol, a Boyd Tinsley distinguished professor of law at UNC, delivered the following remarks at the memorial service:

These last months have been a wrenching and inspiring season of loss, of lost icons, at the University of NC. I think of Doris Betts and Julius Chambers. And the singular, unsurpassed quartet. Perhaps the greatest gift ever bestowed on an American university. Locked in friendship, character, and aspiration. Three Bills — Friday, Guthridge and, now, Aycock. And a Dean, of course, Coach Smith.

You can listen to Nichol’s remarks below:

We mourn the high soul that the other three members of the historic quartet would say was the best of them, Chancellor William B. Aycock. Though, since all four were bathed in a defining modesty, Bill would reject the honor – saying we’d be foolish to think such a thing.

Member of the famed study group of the Class of 1948. Bill Friday, Bill Aycock, Dickson Phillips, Bill Dees, John Jordan, with occasional visits from upperclassman, Terry Sanford. It’s been one of the honors of my life get to know most of that cadre. When I asked each who was the smartest, it was unanimous, Bill Aycock

Judge Phillips would say, Aycock didn’t so much “emerge’ as he “took off and left the pack.” Of course Dick Phillips drinks of the modesty potion as well. But Chancellor Aycock was first in the class, editor-in-chief of the law review, and, when Professor Baer became ill, he asked Bill, still a student, to teach his class for several weeks ‘til he recovered. I have, up here, an affidavit from my own law school dean attesting that none of my professors ever once considered asking me to teach anything. Then or since.

Jack and I have divided assignments. It’s hard to have just one speaker for the best teacher in the law school’s history and the greatest chancellor in this university’s long story. That particular combination has never before been found in one person. It never will again.

The constant servant of duty. To his family, when his father fell ill. To his nation, in war. In Patton’s Third Army – which I understand was no easy walk. To his beloved university, when Pres. Friday asked him to serve as Chancellor. Responding, “I’m happy to take a turn, if it’s understood I won’t stay more than seven years.” “I’m mainly interested in teaching school.” And what a turn it was.

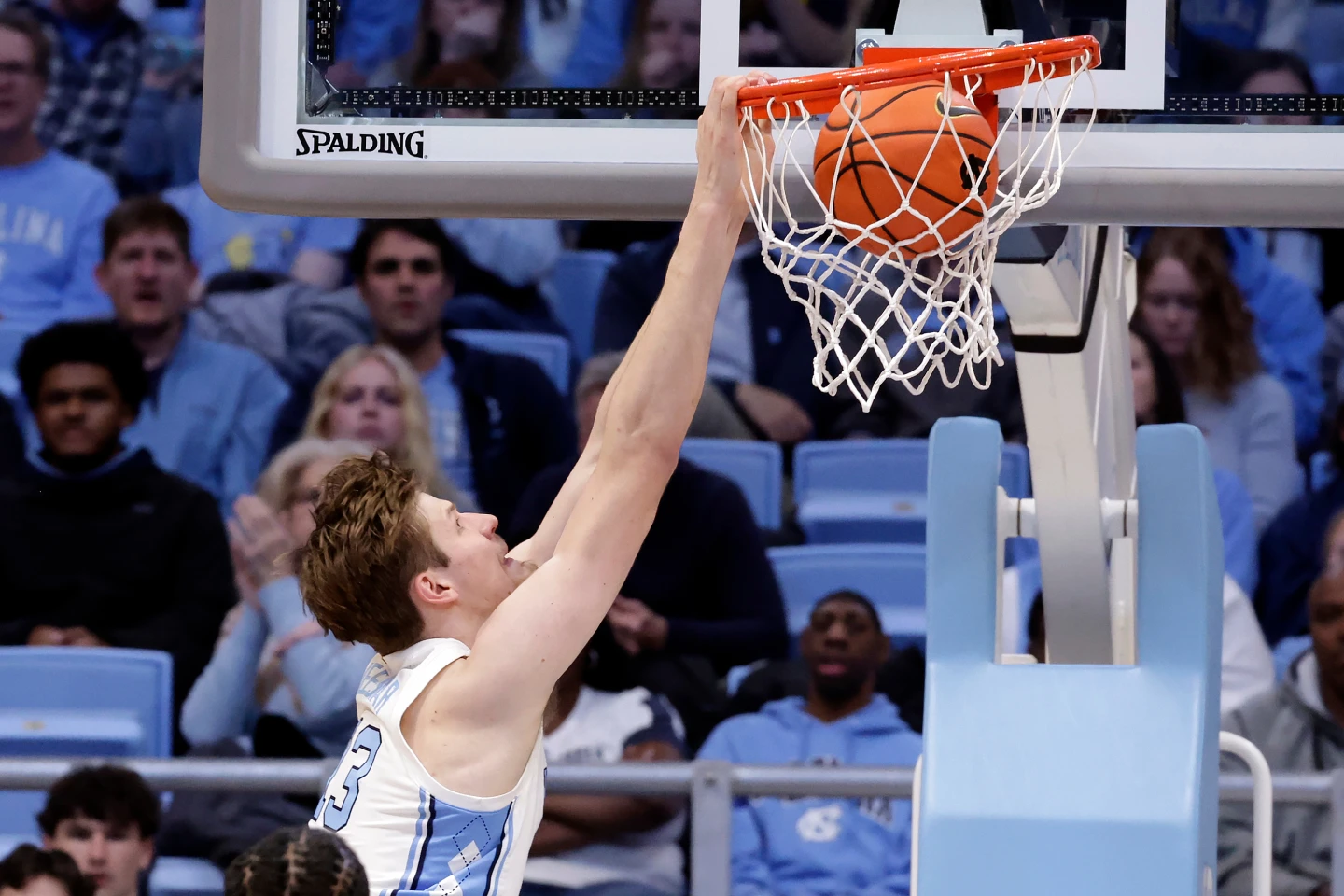

After a basketball scandal, hiring and supporting Coach Smith. When Frank Maguire came to his office, announcing he was going to the Philadelphia Warriors, the Chancellor asked Maguire if he knew where Dean Smith was. “Out in the car,’ he answered. “Well, send him in. “I never even gave him a chance to sit down. I knew Dean and I knew what I wanted. ‘I guess it worked out, didn’t it?’ Coach Smith told me it was true the Chancellor said “I’ll never fire you for losing games; but he added, ‘if you cheat you’ll be gone in a minute.’

In his first days on the job the Chancellor was introduced to boosters who said the Education Foundation was meeting, at that very moment, to fire the athletic director. Bill said, “you might let them know they have one more little hurdle – they’re going to have to get rid of the Chancellor first.” Though “that shouldn’t be much of a problem, I just got here, and I’m not looking to make a career of it.’

When another group came seeking Coach Smith’s head, after an early disappointing season, the Chancellor excused himself from the meeting for a few minutes, came back, and reported: “Gentlemen I’d like to inform you I just extended Dean Smith’s contract. So are we done here?”

And when campus police told him “a group of demonstrators, mostly black, with some children, was marching across the campus, and we told them they couldn’t. Aycock said, ‘you’ll have to go back, find ‘em and tell them they certainly can.” And they’re welcome here at South Bldg.”

And, most important, in the crush of the Speaker Ban. Doing battle on behalf of the institution he loved. Explaining “those entrusted, for the time being, with the University of the people, have a special duty to reject external political and economic pressures, “lest we forfeit our claim to be a university.” UNC was “fathered by rebellion and mothered by freedom. It is an instrument of democracy. ‘We’ve come far, short on cash, but long on freedom.”

When he carried the fight beyond campus walls, legislators, who controlled his budget, and his job, were irate. A Senate leader said he’d had “more than enough big talk from the Chancellor.” He was sick of it. From now on, only supporters of the ban would be named trustees. A Duke official, who shall mercifully go unnamed, said Aycock should ‘be fired immediately.” His own Johnston County Democratic Party passed a resolution condemning him.

So the Chancellor upped the ante, issuing a national call: “Generations of students throughout the breadth of this land have gone from this campus to lead the nation, we need you now to come home, and defend the freedom of Carolina.”

I asked him once how he found the courage. He said when he took the job he told Bill Friday, “I don’t know if it’ll last a week or for years. But I’m going to do what I think is right and then go back & teach my classes.” Old school. Better school. I asked if it helped that one member of his study group was the president of the university and another was the governor? He smiled and said, “maybe, but sometimes, they could be a deadly quiet.”

I’ve read that greatness is given only to the few. In my older age, I think that misses it a little. Greatness may be given to the few, but it is exercised, it is lived, with all its costly demands, only by the very rarest among us. The priceless gem. We are blessed to live in his shadow – here in New Hope Chapel Hill. His marker is one we cannot meet. But it helps greatly to know from which direction the sun does rise.

Chancellor Aycock closed his inaugural with this prayer:

Give us the desire to search for the truth

Reverence to know the truth

Courage to protect the truth

And wisdom to practice the truth

So that we may, together, advance on this earth

Mercy, love and understanding, for all mankind.

Godspeed Chancellor, Teacher, Mentor, Statesman, Hero, Lion, Lodestar. Beacon of character, integrity, service, bravery, selflessness, duty and, finally, love. You have lifted and marked this campus forever. You will be in our hearts longer still. Lux et libertas.

May God cherish this noble, beloved, and most pleasing son.

Jack Boger, who is stepping down from Dean of the School of Law, also spoke at the memorial:

I’ve been asked to share thoughts about Bill Aycock’s impact on the lives of faculty members, staff and students at the School of Law he so loved. I am far from the first to take up this theme, for Bill’s love was warmly and continually reciprocated by the School. When, in December of 1985, Bill Aycock retired after 37 years of service, deans and former deans stepped forward without reserve to celebrate his remarkable qualities.

You can listen to Dean Boger’s remarks below:

Dean Ken Broun wrote in the School’s Law Review that Bill had been “the mainstay of this faculty almost from the day he joined it until the day he retired.” To Dean Broun, Aycock had been always “the ideal faculty member . . . superior in teaching, in scholarship, and in public service,” someone who “consistently supplied his colleagues and his dean with good and wise counsel . . . with good grace and humor.”

An earlier dean, Dickson Phillips, Jr., initially Bill’s law classmate and later, his faculty colleague, remembered Bill not simply as the finest academic mind among the storied members of the Class of 1948. Instead Dean Phillips wrote:

his academic excellence [as a student] was “probably not a fact worth writing about forty years later if that were all there was to it. The important thing . . . is that . . . his quickly established academic preeminence . . . was matched by the affection that his personal qualities as quickly earned. Unassuming, unfailingly civil and sensitive, good-humored, ungrudgingly helpful, even-tempered – he was from the outset and by common consent our peerless leader. . . . Even then you could [also] sense that whatever power might come his way, he was – at odds with the maxim – congenitally incorruptible.

Dickson Phillips’ predecessor, Dean Henry Brandis, praised Bill Aycock’s character, integrity, hard work, common sense, uncommon intelligence, self-discipline, exacting standards for himself, devotion to School and University . . . “Others will teach his courses and sit in his faculty seat,” Dean Brandis observed, “but in the sense of equivalency, he will not be replaced.”

I wish I had time to lift up later, beautiful tributes authored by Dean Judith Wegner and by Dean -Designate Martin Brinkley. But I must turn to his impact on our staff and students. In some ways, the deep, very personal affection the Carolina Law staff has always felt for Professor Aycock is the surest mark of his greatness as a human being. For staff members have a way of finding out about their bosses’ character, and they found, first hand, repeatedly over days and weeks and years of interactions, that this brilliant professor and chancellor was always interested, truly interested, in them and their lives, remembering their children, asking about their personal concerns, and always with humorous self-deprecation and modesty, generous with his time, a genuinely good man.

And let me reflect on the student view, on why he had such an unparalleled impact, as a teacher, on three generations of students. First, the bare statistical evidence. Beginning in 1967, the School of Law first offered an annual teaching award, the Frederick B. McCall award, bestowed by a vote of the graduating third-year class on their single most outstanding law professor. During five years of the nineteen years between 1967 and his retirement, that third-year class choice fell to Bill Aycock – a singular honor in a faculty so full of great and devoted teachers: no one in that era even came close.

And I can reliably confirm that those awards were no passing whim of the moment, for I’ve since heard hundreds of alumni, graduates from the 1950s, 60s, 70s and 80s reflect back on their law school days in Chapel Hill and quickly single out Bill Aycock, as the greatest professor they ever had, and the greatest influence on their subsequent professional lives. [Stop]

Why? Bill possessed, first of all, the great teacher’s love in conveying, not his own views or personality, but the joy and mystery of his subject — the law in all its grandeur and complexity. Like a great teacher of anatomy, he would show his classes, not simply the thigh bone and the sternum and the bicep – the basic frame of the body, to carry on the metaphor — but the miraculously complex interrelationship between bone and muscle, tissue and sinew, organ and cell. He brought — ‘the law’ — to life in the classroom, conveying through his distinctive, Eastern North Carolina accent and his slightly mischievous smiles, and lively, droll classroom examples the sheer joy and excitement of discovery.

He even made you believe you might possibly continue on that journey yourself, might carry out personal explorations into law’s meaning and uses, long after you were sent forth to practice law on behalf of future clients. Dean Judith Wegner once tried to capture this quality of Bill’s teaching by quoting an observation from William Butler Yeats: “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.”

This alone was a great gift –enough to merit five teaching awards. Yet beyond that great gift – his capacity to convey the excitement and gratification in ‘finding’ and ‘discovering’ and ‘apprehending’ the law – Bill Aycock silently and simultaneously guided us through a more central course of study – an almost daily meditation upon a theme that . . . religious traditions, and our Greek and Roman philosophic heritage have deemed of central importance – the nature of virtue, and its value — subjects somewhat out of fashion in many contemporary circles.

It is here, I think, where Bill Aycock rose beyond even the finest ‘technical’ teachers of the law. For through his own behavior, through the links he constantly made between law as doctrine or rule, and law as aspiration and spirit, Bill Aycock taught generations of Carolina Law students that their chosen discipline could be noble and fine, that lawyers might use law to advance justice and goodness.

As one of Bill Aycock’s students from 40 years ago, I can attest, along with countless others before and after – that we needed no formal lectures on ethics, or professionalism, or the Model Rules, to apprehend Bill Aycock’s deep and abiding commitment to these ideals, and to sense our own obligation to live out such a creed, every day, in our professional lives.

Dean Phillips closed his 1986 tribute to Bill Aycock with what I might call a profession of faith:

I have deliberately emphasized, Dean Phillips wrote, the qualities that allow me to use the heavy words ‘hero’ and ‘noble’ freely . . . For I have no doubt that, in the Grand Reckoning . . . Bill Aycock deserves that grand appraisal.

None of us here has yet witnessed that Grand Reckoning day, though some have faith it will come, and may indeed already have come as Bill Aycock gave over his mortal frame last Saturday evening. But I join Dean Phillips and possibly many of you in this sanctuary, in the conviction that, insofar as it is given to humankind to judge one another, William Brantley Aycock will be found worthy . . . and sanctified in any such Reckoning. He was, and always will be – to our faculty, our staff, our students and our alumni, and I dare say, to this University and the State he loved and served — the perfect exemplar of what we hold dearest, what we value most, what we have most loved.

Daniel Leigh, Aycock’s son-in-law, also spoke at the memorial. He recalled his introduction to Mr. Aycock:

I first met him in 1962, at the Chancellor’s house; I was in the ninth grade and had asked Nancy for a date, my first ever. There we were, Bill and I, in the sunroom of the chancellor’s house, both sitting at attention. I remember wondering if all dating was like this and, if each time, I had to pass muster with the most important person on campus.

You can listen to Leigh’s full memorial below:

In the mid-1970s, when Nancy and I reconnected, I think he grit his teeth a little bit when I told him I’d be around a while longer. When I asked what I should call him, he said, “Wild Bill.” I breathed easier.

I never attended one of his lectures until the year he retired. When I did, I listened intently, happy not to be responsible for learning any content. His body language and gestures intrigued me; to emphasize important points, he flexed his eyebrows. His audience seemed entranced. Such a convincing storyteller, he made the law the most engaging, accessible subject imaginable.

Beyond the lecture hall, I learned a lot from him.

Kind of his recipe for a full life. Our relationship was mutually beneficial; I was his eyes and ears on events and news; he was my window into his ever-expanding world. He called me his secretary, but I liked executive assistant better. I was his driver, his straight man; he was definitely the funny one. I have based a character in a book I’ve written on Bill as a young boy. Did I say our relationship was one of mutual benefit?

Bill regaled me with tales of his childhood in eastern NC. Going to court with his father, a judge; seeing how justice was done; noting which lawyers were prepared, and which weren’t. His father’s common sense approach to applying the law. For Bill, it was an early fascination with the law.

Bored by retirement? Not Bill. At CM, he reinvented himself. He kept up with an expanding list of new friends, his family and certainly all things UNC. His curiosity had no limits; in recent years, I did countless Google searches at Bill’s behest; the subjects were wide-ranging, but his curiosity tended to stay in this hemisphere.

His pet projects. After the Univ’s bicentennial celebration, he arranged to get a sapling descendant of Davie Poplar planted in the front landscape of CM. He monitored the tree’s condition and during a drought even hauled water to it via his golf cart.

Growing old by learning something new was how Bill aged. The Roman Cicero, who wrote a fair amount on the subject, would have appreciated Bill’s approach. Said Cicero, “For as I like a young man in whom there is something of the old, so I like an old man in whom there is something of the young; and he who follows that maxim in body will possibly be an old man but will never be an old man in mind.” That was Bill.

He welcomed everyone, young and old. Once the Cox family came from High Point for the first visit for the three young children, Bill’s great-great-niece Karli and her two brothers. Excited, Karli ran ahead to Bill, looked him over and hollered back to the others, “Well, he doesn’t look 92.” He loved telling that story.

When his great-grandson Preston was born, Bill proclaimed, “He has thrust me into greatness.” But his name and the word “great” have been joined for a long time: decorated soldier, exemplary teacher, courageous chancellor, mentor to practicing lawyers, caring father and grandfather. Bill experienced immeasurable pride at the 2012 start-up of Aycock and Aycock, a Greensboro law firm of his son, William Preston Aycock and his grandson, William Brantley Aycock II.

Pride in accomplishment. This incredible man of great accomplishments, always said he was proudest of his decision to marry Grace. They married on Oct. 25, 1941, the day before his birthday. “I did that so I would never forget our anniversary,” Bill said. They were a team in every sense. When he went to Europe in WWII, she soldiered on with their young son. When Bill became chancellor, Team Aycock met the enormous challenges of public life with resolve, purpose and good humor. So it was entirely appropriate they both received UNC’s Distinguished Alumni awards. Bill joked theirs was a 50-year marriage contract, and it was up to Grace to renew. She did.

An unparalleled work ethic. His sense of hard work was forged during the Depression and tempered by military service in WWII. Thus as Chancellor, walking to South Building following a snow was nothing for Bill. When WCHL radio called asking if classes would be held, Bill said, “I’m here and I’m waiting for ‘em.” (gesture with fingers) The announcer told the radio audience, “Chancellor Aycock wouldn’t call off a day of school come hell or high water.”

Even in his 80s and 90s, Bill, who never practiced law in the conventional sense, gave back to his profession, offering counsel to practicing attorneys seeking it. I too learned about his approach to solving problems: he got all of the best information about a subject; he used an uncommon focus, weighed the issues calmly and made decisions. Some required more attention, but they all got the Bill Aycock treatment.

For example, as Chancellor he confronted a landscape dilemma; reconfiguring a parking lot required moving a number of boxwoods. “Chapel Hillians love their trees and vegetation; heck, I do to,” Bill said. What to do? He conspired with the building and grounds superintendent to have the bushes moved about 6 feet, in the middle of the night. (S-H-H-H) To Bill’s delight, the clandestine act went undetected and maybe unknown by most people until today.

Interpersonally, Bill acted in much the same way, quietly, behind the scenes. I have experienced — firsthand — and have witnessed countless acts of his generosity. Once I asked him about it. “I just help people when they need it, rather than wait until later in my life when it might be easier for me.”

Bill has a great many friends. Ray Dawson, John and Brenda Jordan visited often. Always when John entered Bill’s room in the Health Center, he’d say, “Where’s my chancellor?” Bill loved the grand entrance and his friend of 66 years. By chronology, Bill was not John’s chancellor nor mine, but we claimed him.

I would be remiss and certainly Bill would want me to thank all those capable people who lovingly cared for him both at the Fairways Assisted Living and the Health Center at CM. Many went the extra mile with him; some became his friend. Said one: “He always asked about my family. He made me feel like the most important person in the room.” When anyone, including CM staff, left his room or apartment, he always said, “Thank you for coming.” Many CM staffers have told Nancy and me, they’ll miss him. We will too.