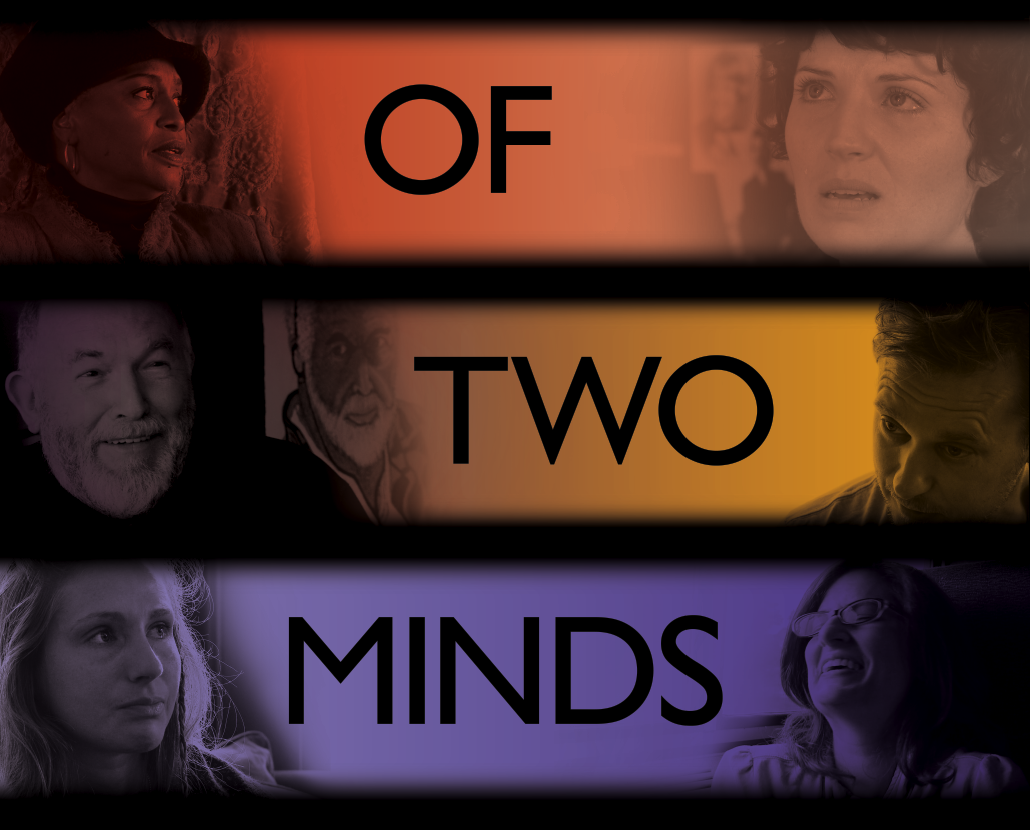

The film shifts in and out of stories of pain, hope, connectivity, isolation, and struggle—following various adults who are afflicted with, but not defined by, bipolar disorder.

The film shifts in and out of stories of pain, hope, connectivity, isolation, and struggle—following various adults who are afflicted with, but not defined by, bipolar disorder.“Of Two Minds” was directed by Lisa Klein and her husband Doug Blush. After premiering at the Cleveland International Film Festival last April, the documentary has been shown throughout the country—at various festivals. The film arrived in Chapel Hill last Wednesday for a one-time showing at the Varsity theater.

A full house gathered for the free event, which was followed by a panel discussion and question-and-answer session. The film was created in memory of Klein’s older sister, Tina, who ended her own life eighteen years before the film’s creation, after a struggle with bipolar disorder.

Klein and Blush’s documentary captures the day-to-day existences of different individuals as they manage and pursue rich and multi-faceted lives while coping with bipolar disorder. The majority of the film is narrated by four adults of different ages who have the disorder, with occasional explanations and ideas offered up by psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental illness advocacy leaders.

The family members, lovers, and support networks of those who are profiled also add their voices to the fabric of the narratives—lending insight and perspective. Their accounts help speak to the variety of experiences and challenges that greet those whose loved ones are afflicted by a mental illness. The inclusion of these loved ones also emphasizes the idea that people with bipolar disorder are still, first and foremost, people. They are individuals with whom others fall in love. They are people with families and friends—with jobs, responsibility, and complex networks of relationships.

The film’s focus is upon allowing others to hear about mental illness from the mouths of those who are affected by it. The directors sought first-hand accounts in order to depict bipolar disorder as one facet of a life instead of an identity in and of itself.

The voices of professionals are used minimally and in a way that allows the authority of narration to remain firmly in the hands of those with the disorder. The individuals featured in this film were followed for a significant span of time—through the advent and dissolution of romantic relationships, the discovery and processing of a diagnosis, and changes of treatment regimens.

The documentary was brought to the Varsity by Donna Kay Smith and hosted by Accessible Minds, LLC. This group, founded by Donna Kay Smith and B.B. Smith, works to provide multi-media resources to people with mental illnesses and their family members or loved ones. With these resources, individuals will have the opportunity to create something—to give voice to their lived-experiences, perspectives, and struggles.

“Of Two Minds” immediately resonated with Donna Kay Smith, who quickly got in touch with the filmmakers and asked about gaining a copy of the DVD. They informed her that they weren’t giving out copies yet but were screening the movie around the country—usually with discussion panels afterwards. She thus began her efforts to bring last Wednesday’s event to life.

Smith herself is enrolled in Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies. A longtime mental health advocate and certified rehabilitation counselor, who, ten years ago, was faced with the discovery of her son’s severe mental illness, Smith is deeply passionate about de-stigmatizing mental illness and giving voice to those affected by bipolar and other disorders.

“One of our goals at Accessible Minds is to help people make connections with others who live with mental illness so that they can learn that their experience is not wholly unique—that they’re not so completely different form everyone else,” said Smith. She wants people to feel less isolated and aberrant—less thoroughly marked by difference.

Among other aims, Smith is interested in bringing the word “normal” into conversations about mental illness. “We’ve got to start using this word—because there are things that are “normal” when you’re dealing with different disorders,” said Smith.

When considering her options for advocacy and action, Smith recalls, “I really decided I wanted to go the multi-media route, and that’s when I enrolled in the Center for Documentary Studies. I saw the trailer for “Of Two Minds,” and I was like, ‘oh my god, that’s the documentary I want to make,'” she said.

The film emphasizes the idea that living with bipolar disorder is a constant process—a process whose methods must sometimes be re-worked and reconsidered. The individuals followed have different personalities, lives, and experiences of mental illness. The documentary highlights the fact that there are common experiences—recurring struggles to deal with the manic highs and the devastating lows. Yet, at the same time, the adults who are chronicled vary in terms of their responses to medication, their preferred manners of coping, and the ways in which they have incorporated their bipolar disorder into their identities.

Carleton, a 65 year old artist who was diagnosed quite late in life, after many harrowing travails, embraces medication and has had a very positive response to it. He doesn’t find that it stifles his creativity. With his diagnosis and on medication, Carleton’s wife, who has acted as an astoundingly loyal support system, says he is the happiest she’s seen him in many, many years.

Cheri, on the other hand, has begun easing off of medication by the end of the film—finding that it limits her creatively. Her alternative, holistic approach seems to be working for a while. (However, the information we are given at the very end of the movie tells us that she is back on medication, highlighting the idea of life with mental illness as a continual process. There is not merely diagnosis and then treatment and resolution.)

Cheri tells viewers about the manic highs of bipolar disorder, describing the colors as more vibrant, more beautiful. She says it’s like taking your best day and multiplying it by a million. She wouldn’t want to go without those unique experiences. For all the incredibly tough, dark times, there is also something about bipolar disorder that has enriched her life, she says.

An interesting contrast is drawn between Cheri and Liz, another of the movie’s subjects. Liz defines bipolar disorder much more wholly as an illness—as something purely adverse. She feels that her disorder interferes with her life and her identity more than it helps to shape or enrich it. These sorts of differing perspectives lend a richness to the film—helping it to more thoroughly investigate what it means to live with bipolar disorder.

Liz is a writer and editor for a Philadelphia publication. She gained fame and a bit of a following through a column she writes—addressing her bipolar disorder. She has also, more recently, started posting youtube videos featuring updates about her mental state and life. She receives masses of positive, encouraging, and intensely grateful responses. Though she may choose not to be afflicted by the disorder, unlike Cheri, if given the chance, she has also found something positive in it by reaching out—by forging and becoming a part of a community.

Smith feels that helping people with mental illness to find a voice, to tell their stories, and to discover a community will help them to refuse the stigma of their disorder. They can, she said, “start to derive strength and identity from their experience.”

“If people who have mental illness buy into the stigma, then you’re not going to change it from the outside in,” Smith added.

The film resonated with Smith because it portrays people with mental illness as members of society—as people with lives and relationships. They have real, often messy struggles due to their disorders, but they are also people like anyone else with normal human components to their lives.

Often we receive images of mental illness as highly sanitized and simplified with too neat—too glossy—a finish (think “Silver Linings Playbook,” “A Beautiful Mind” and other film depictions of mental illness). Or else we get horror stories of mentally-ill loners turned violent. “There need to be multi-dimensional portrayals that don’t capitalize on fear or rely on simplification,” said Smith.

“Of Two Minds” is a good start. It offers up a full, rich, and well orchestrated portrayal of life with a very serious mental illness. The panel after the showing included director Lisa Klein along with two adults with schizoaffective disorder and the mother of a son with schizoaffective disorder.

“I didn’t want a panel with a lot of professionals because that tends to happen a lot. Everyone else gets to talk about mental illness, but we don’t really hear about it from the people who have to live with it,” said Smith.

Smith and others hope that hearing direct, first-hand accounts of mental illness will help to thwart misconceptions and simplifications. Perhaps more importantly, such films and such platforms may help those who are actually affected to get a say in the depiction of mental illness.

Wednesday night’s event, and other similar efforts seek to effect change by removing the stigma and empowering voices. The movie, the panel discussion and the goals of B.B. Smith and Donna Kay Smith’s Accessible Minds endeavor are powerful examples of grassroots efforts to force the issue of mental health and mental illness out of the margins of our society—one first-hand account at a time.