“Viewpoints” is a place on Chapelboro where local people are encouraged to share their unique perspectives on issues affecting our community. If you’d like to contribute a column on an issue you’re concerned about, interesting happenings around town, reflections on local life — or anything else — send a submission to viewpoints@wchl.com.

Why Is Housing an Environmental Issue?

A perspective from Melissa McCullough

As Chapel Hill contemplates strategies to alleviate its housing crisis, many conversations are taking place about how our neighborhoods may change — and what those changes might mean.

I’ve spent a long career working in environmental sustainability, and climate change is my primary focus in retirement. Last month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its 2023 report on climate change, and scientists gave us a “final warning” on the climate crisis, warning that only swift and drastic action can avert us from irreversible catastrophic warming.

It was a warning we must take seriously, and one where local governments and housing play a vital role.

In their report, the IPCC scientists recommended that we adopt sustainable land use and urban planning (e.g. more infill and less suburban sprawl.) This strategy is also championed by the Sierra Club which recently released a wonderfully informative compendium of whys and hows of building housing while minimizing sprawl and reducing vehicle miles traveled.

In this essay, I will explore the ways in which sprawl — that is, low-density development in suburbs spread out over larger distances — is devastating to the environment, and why housing is a critical environmental issue.

The 70s were a boon to environmentalism, and not-so-great for housing

If you grew up in the 1960s and 70s, this linkage may seem counterintuitive. We remember the early days of the environmental movement, when problems were visibly obvious — smog, water pollution, the Cuyahoga River catching fire — and solutions were equally so. We worked hard to pass the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts to make our communities healthier. (You can see the immediate effectiveness of these strategies by looking at emission trends.)

But the 70s and the era of battling highly visible problems with straightforward solutions like regulating auto emissions and banning DDT are long gone. As the IPCC report noted, “There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all….The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”

We are now in the era of preventing the absolute worst: protecting the planet from runaway warming due to greenhouse gases. We must act quickly and decisively, and “across all sectors and systems … to achieve deep and sustained emissions reductions and secure a livable and sustainable future for all.”

Our chance at an ounce of prevention for climate change was decades ago. Sadly, instead of doing what we needed to, we continued to dig ourselves deeper into that hole.

Those years of curbing obvious pollution were also years of urban sprawl. People moved out of cities and into suburbs, which made them car dependent for commutes and for everyday life. One of the places where local communities can have the most impact on this is the way we build future housing.

How we get around is a large source of greenhouse gases

The result of car dependency is that the largest source of climate-changing greenhouse gases across the country and in North Carolina is transportation. Passenger vehicles alone account for 15 percent of all greenhouse gases emissions globally. Significant gains in efficiency, cleaner fuels, cleaner cars and the like can’t make up for our proclivity for driving and for bigger cars, trucks and SUVs.

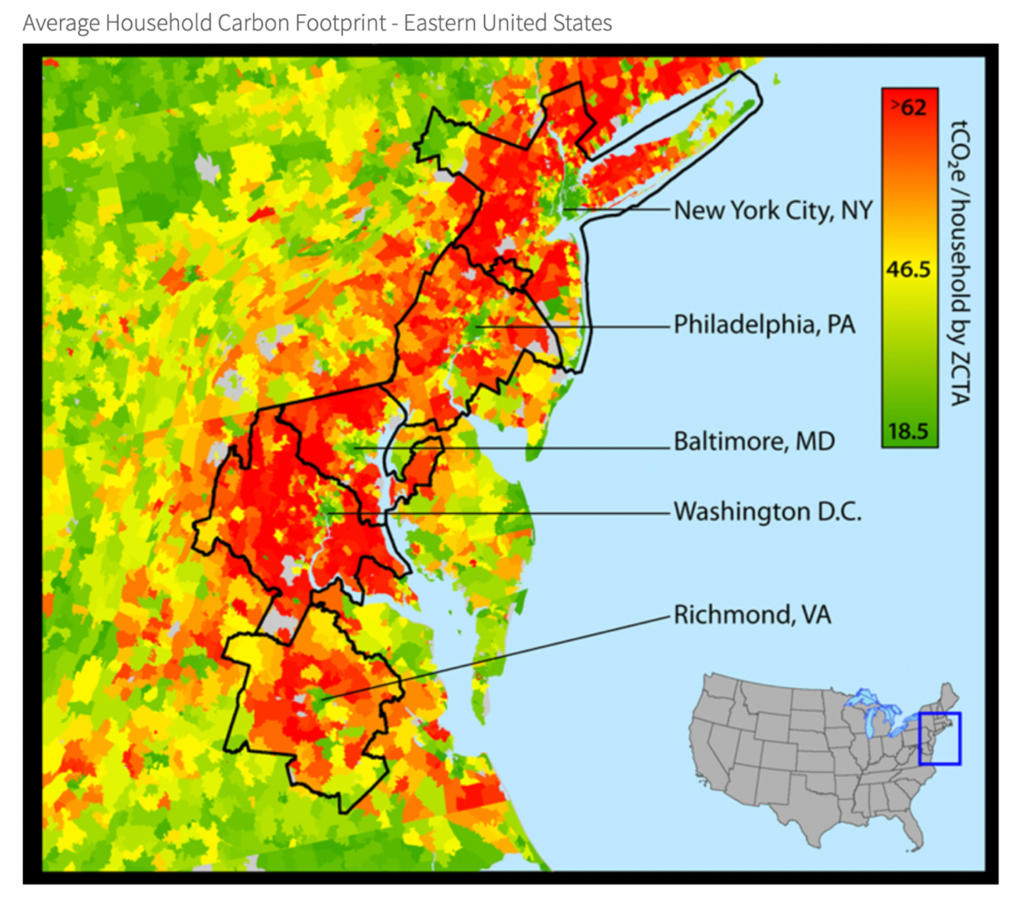

The IPCC reported that transportation is the largest fraction of climate pollution because of the way we have built our lives around cars and sprawled our lives out, measured with ever-increasing Vehicle Miles Traveled. Places where people have to drive everywhere because they live further from jobs and daily needs have larger carbon footprints. This is very clear on the mid-Atlantic map of Average Household Carbon Footprint, below, where the walkable city cores, shown as low carbon-footprint green, are surrounded by deep red, high carbon-footprint sprawl. In our area, emissions per person even increased 7% between 1990 and 2017.

When the suburbs were designed, we separated single-family houses with large lawns from other land uses (commercial, industrial), ostensibly for health and safety reasons. But our single-family zones were also designed to be exclusionary for Black families, as the White House recently noted.

Building our suburbs in this manner eliminated the very kind of mixed use, walkable, transitable downtowns that now engender nostalgia, and that we love to visit in Europe.

Sprawl creeps out

The incremental creep of single-family developments spread each American town and city out like spilled milk. In Chapel Hill, around two-thirds of our land is reserved for single-detached houses with private yards (like most U.S. communities).

The area around Chapel Hill has changed too. As inner-ring suburbs near good jobs filled up and got more expensive, outer ring suburbs developed. (We may not be Atlanta, but you can trace Chapel Hill development outward from UNC over time.) Highways were extended, and people’s commutes got longer.

In Chapel Hill, 40,000 people commute in every day to work, most alone in their car, because they can’t afford to live here and there’s not good regional transit.

Separated land uses also meant separated daily needs – schools, doctors, restaurants, parks – to which one had to drive, often many trips a day. The spreading out of shopping started with strip malls, then to regional malls and big box stores. The trees mowed down for highways and parking lots met with little protest because, hey, we can get further faster and there’s more shopping there.

In their report, the IPCC pointed out that we can NOT address transportation-related climate pollution without addressing the integrated causes of our Vehicle Miles Traveled. Luckily, cities’ authorities and opportunities for doing so are significant.

According to IPCC’s latest report, “Integrated spatial planning to achieve compact and resource-efficient urban growth through co-location of residences and jobs, mixed land use, and transit-oriented development could reduce GHG emissions between 23-26% by 2050 compared to the business-as-usual scenario.”

In other words, we must locate housing near jobs, we must develop land to support multiple uses (to reduce car trips) and we must design our future communities to be less car-dependent.

Chapel Hill is working on all of these, and these actions will have multiple economic, health and green space benefits as we get closer to having more of our daily needs accessible without a car.

Destruction of green space

Sprawl wastefully ate up green space – farms, habitat, and carbon-sequestering trees, while densifying housing can protect more forest outside our boundaries.

Wait, you say, what about our lovely single-family neighborhoods, with trees and gardens? Well, unless the houses are surrounded by 150-year-old oak and beech trees, they were built by tearing out all or most of the trees, building the homes and planting little trees and bushes.

My neighborhood in downtown Chapel Hill, which had been forest, 1915

Especially as families have gotten smaller and houses bigger, single-family homes have caused more destruction per person than multifamily homes. Habitat in these yards is usually fragmented, non-native, and chemically-treated, with lawns which provide little wildlife or pollinator benefit. In short, they do not replace the kind of habitat they supplanted, while they require paving over more miles of streets per person, as well.

The strip malls, malls and big box stores that were separated from housing and built outside of town were created to draw commerce away from the locally-owned downtown stores (where local spending bounces around locally). In addition, the acre upon acre of parking lots are always oversized so they can hold the peak Black Friday shopping crowds. Those forests or farmlands, which provided food or habitat and other ecological benefits, were replaced by large urban heat islands, with their attendant environmental damages.

Obviously, humans have to live somewhere, and many people don’t want to live in apartments, but the sprawl version of how that happened was much more destructive than it needed to be. If a third of residential building had been duplex, triplex or quadplex, Chapel Hill’s low-density zones could hold around twice the number of homes presently in Single-Family-Only zones, more like Southern Village. In fact, this would be a reflection of historic housing patterns, as seen, for example, in popular Trinity Park, Durham. This would likely mean that land prices would be less, and many of our teachers and university staffers could be living here, instead of commuting here.

It must be said that to be sustainable and livable, denser communities must also have good active transportation systems (bike/ped) as well as ample interspersed trees and other green space for human health and ecological benefits.

Flooding/stormwater

Past policies caused our present flooding and stream impairment problems, while denser housing has less impact per person.

How much stormwater runs off a piece of property depends on the amount of impervious surface and if/how the stormwater is controlled. For decades, stormwater control was “get it off the streets fast.” This worked when places were small and rainfall was manageable. Many communities actually caught and treated runoff with sewage. But with increased impervious surface and climate-induced heavy rainfall, these now get overwhelmed and overflow, dumping raw sewage into rivers. That’s luckily not us, but what Chapel Hill has seen is the similar overwhelming of old conveyance infrastructure with resultant flooding of low-lying areas (e.g., Eastgate or Franklin in front of Chipotle). Thinking less selfishly, our stormwater also combines with that of other cities to flood downstream places like Princeville, on NC’s coastal plain.

We have begun to address these problems by requiring new multi-family and commercial development to manage stormwater runoff – to delay it and infiltrate as much as possible. But old and new single family home developments, with their higher impervious surface area per person, are not required to do any stormwater control at all.

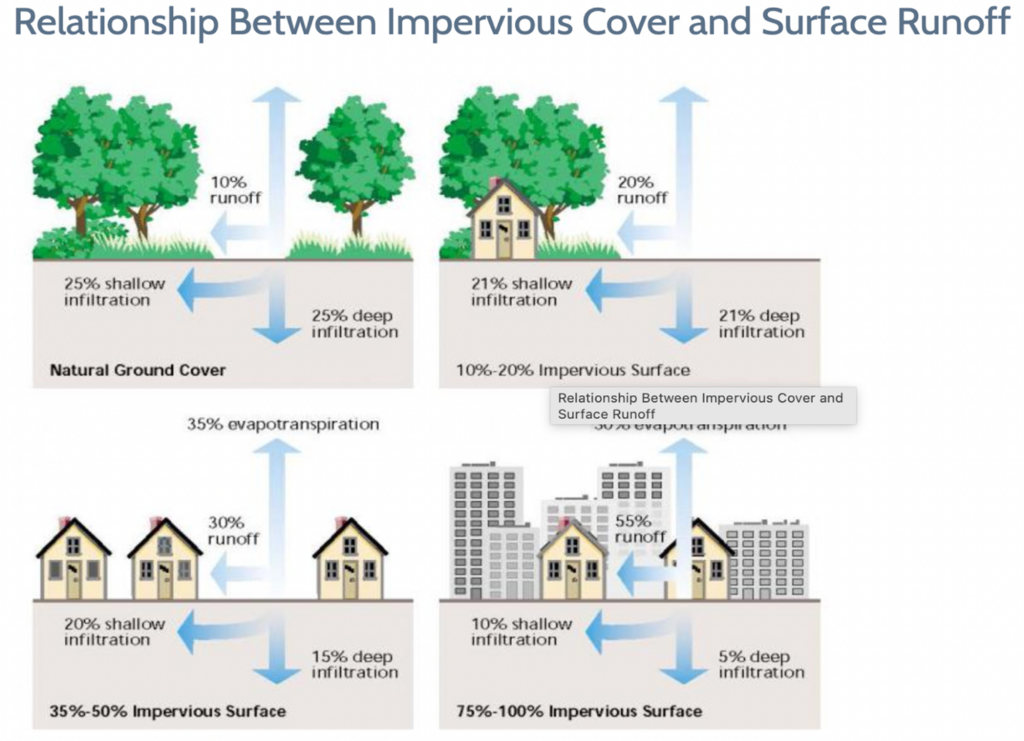

The graphic below shows how, as impervious surface increases, runoff increases and infiltration to aquifers decreases. What you should notice when you examine this graphic, is how much difference there is in runoff per housing unit between the third scenario and the fourth. This is not to say Chapel Hill should look like the fourth, but that we need to acknowledge the relationship between impervious surface and population housed (just as we should look at trees destroyed per person.)

https://toolkit.climate.gov/image/2907

The other thing to note is that “As little as 10 percent impervious cover can result in stream degradation.” (Green Infrastructure Guidance for Flood Reduction). When ⅔ of Chapel Hill is in the 35 – 50% impervious surface area category around our many urban streams, one must conclude that the impact of all that single family housing is significant, and even more significant per person than denser housing.

Population

Population increases are inevitable, so we must plan to accommodate them sustainably.

I know it’s frustrating to see a beloved place change with population growth; I grew up in a no-longer-small town. And it’s tempting to say, “Let’s close the door!” Sadly, that can’t actually be done, and climate migration to less vulnerable places, like ours, is expected to increase. Modeling and addressing expected changes is a much better foundation for sound policy than nostalgia.

A great quote I heard at a smart growth conference was, “People hate two things: sprawl and density.” But with a growing population, our choice is one of the two, and we already know the ecological destruction that comes with sprawl.

Budget issues

It is more costly to provide single family neighborhoods with infrastructure and services than denser housing and mixed-use areas.

Right now, you can see the footprint of Chapel Hill on a map, within which are existing streets, utilities, fire stations, transit and other services provided by the Town with our tax dollars. Any housing that we can fit within that existing footprint can be served by existing infrastructure for marginal cost. However, if we continue to sprawl out, we must build, and maintain, expensive new infrastructure. If you look at tax revenue vs infrastructure costs (net revenue) of property types, you can see that single family housing runs in the red; it won’t pay for its supporting infrastructure before that needs replacing. When the majority of your community is single family housing, it’s like the car salesman saying, “I lose money with each car deal, but I make up for it with volume!”

There are some who believe that tapping new housing onto existing utilities would overwhelm capacity, but, in fact, as families have gotten smaller, those single-family zones have actually expanded capacity. Also, densifying population means we could afford to serve more areas with transit, allowing more people to save on transportation costs and getting more cars off the streets.

How can we plan for a more resilient future?

Change is coming, in population growth and climate impacts. We can plan for them in a way to be resilient and create a fulfilling quality of life, or we can wait for them to happen and leave future generations to clean up the ever more expensive mess and live with the dire consequences. My 30-year-old daughter (who works in sustainable food systems, so she understands what’s coming) told her Republican aunt, “We live in an apocalyptic hellscape… the LAST thing I’m worried about is getting married!” My goal is for her to feel that she has a hopeful future, but we have a lot of work to do for that. Perpetuating the past policies that got us here will not get us to sustainability. Luckily, expert organizations, like the US EPA, the American Planning Association, and issue-related research institutes, have been examining effective solutions for decades.

These needed policies, including the one that the Chapel Hill Town Council is honing right now, need not be a scary thing. Mixing multi-family homes and single-family homes is a traditional American housing pattern. I have also written how denser neighborhoods, with green space, cafes, and facilities to walk, bike and roll are happier places. These policies are necessary and these are also what can give us sustainable, livable, healthy, and green leafy places in our challenging future.

Melissa McCullough has a Masters of Environmental Management from Duke in Applied Ecology, and had a 36-year career in governmental environmental agencies. She was the first in the NC government to address stormwater runoff and nonpoint source pollution while at the NC Division of Coastal Management. At the US EPA for 32 years, she worked on a wide range of environmental assessment and problem-solving areas, focusing especially on community sustainability. In 2014, she was the EPA reviewer for the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) chapter on Human Settlements, Infrastructure, and Spatial Planning. She retired in 2020, as the Senior Sustainability Advisor and Assistant National Program Director of the Sustainable and Healthy Communities Research Program. She now serves as the Chair of the Orange-Chatham Group of the Sierra Club.

(all images in this post were submitted by the author, and were not sourced by 97.9 The Hill and Chapelboro.com. Please contact us with any questions/concerns)

“Viewpoints” on Chapelboro is a recurring series of community-submitted opinion columns. All thoughts, ideas, opinions and expressions in this series are those of the author, and do not reflect the work or reporting of 97.9 The Hill and Chapelboro.com.