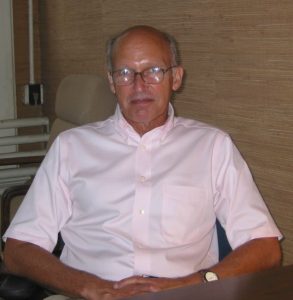

Cecil Wooten was not ashamed growing up gay in 1950s Eastern North Carolina and, now approaching his eighties as an Professor Emeritus of Classics at UNC, that hasn’t changed.

“I wasn’t embarrassed about being gay,” Wooten said. “And I certainly didn’t feel guilty about it.”

He grew up in Kinston, North Carolina, a small town just west of New Bern, with less than 20,000 residents today. His family had lived in Kinston for many generations and was well-respected and well-known, with his father’s medical degree from Harvard University paving the way for their esteemed reputation. He knew who he was from a young age, Wooten said, but he wasn’t the only one who knew.

“When I told my father, he said, ‘I’ve known that since you were about 12,’” Wooten said. “And he told me, you know, ‘I don’t have any problem with it.’”

His family reacted better than he expected, but he had a major obstacle still sitting in his path: figuring out the rest of his life.

“My only problem was I didn’t know what to do about it,” he said. “Because, you know, in 1955 in Kinston, North Carolina, being gay — openly gay — was really not an option.”

In Kinston, there were only two gay men Wooten knew about, and opportunities to learn and explore his sexuality were limited. But in Davidson, where Wooten attended Davidson College, a small institution described as being “composed of almost completely men out in the middle of nowhere.” There, the conversation around the queer community increased, ever so slightly, in volume.

“Homosexuality was [still] something you just didn’t talk about. People were very nervous about it, but it’s really interesting,” he said. “I had five good friends at Davidson. And although we never talked about being gay, and some of them actually pretended that they weren’t, every single one of them turned out to be gay.”

This was the original “gaydar,” he said, even though they didn’t know it at the time.

“Later when I discovered that they were, it made sense,” he continued. “We were self-selecting.”

This tale of college being a new experience for “self selection” upon quietly public and hesitantly private queer folks rings stunningly similar to that of Mark Kleinschmidt, the first openly gay mayor in Chapel Hill.

For Kleinschmidt’s second year at Carolina — where he chose to attend because of the influence of the first gay town council member in Chapel Hill, Joe Herzenberg — he lived in a living-learning community. The point of the program was to room and attend classes with students who were culturally different from you.

“You had classes with folks who had all committed to embracing diversity and it was in that environment that I came out because it was a very safe environment for someone to be different,” Kleinschmidt said. “I was surrounded by other students and in a community that was very welcoming and allowed me to be myself.”

This program was specifically appealing to the queer community at Carolina in that time because it was composed of people who were so committed to embracing diversity and differences. The proof of this concept came later in Kleinschmidt’s own dorm room.

“My roommate, who was supposed to be different from me, actually turned out to be gay,” he said with a laugh. “We came out together in the same year.”

Former Chapel Hill Mayor Mark Kleinschmidt. (Photo by SP Murray)

This picture of safety and inclusion is one many associate with Chapel Hill today — a place where you walk past a “Queeramid” in the downtown square and can hear Latin pride music floating down Franklin Street for the month of June. According to Hooper Schultz, the Chapel Hill community and UNC was unique from the start, and not much has changed.

“UNC is a really interesting space because out of all the college campuses that I study in the U.S. South it’s the only one that didn’t deny the student activists their rights to assemble as a student group on campus,” Shultz said, referring to other universities he studies like Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA.

Like so many others, Wooten’s world as a gay man cracked wide open when he arrived at UNC. The association Schultz referenced to was established in the spring of 1974 — The Carolina Gay Association — and they had Cecil Wooten to thank for that, as he became the faculty advisor of the program.

Aside from the student group, though, Wooten was instrumental in protecting the queer community at UNC in the 1970s. He began his work in activism at the academic level by petitioning for LGBTQ-oriented courses to be taught as part of Carolina’s curriculum. Then, a few years later, he was given the gift they’d been waiting for.

“It was in the mid eighties when the provost called me and said that a man in San Francisco, a doctor who had gone to UNC Med school, had died and had left the university about $350,000 to encourage gay and lesbian studies on campus,” Wooten said. “I remember he said to me, you know, as far as we’re concerned, this is really not very much money and we normally wouldn’t even be interested, but we think this is a worthy concern. Would you be willing to form a committee that would disperse this money?”

Wooten’s answer was simple and easy — he’d be delighted to champion the curriculum that was “at the heart and soul of the university.” The program he helped create is called “Sexuality Studies” at UNC today.

“I used to say at the university that, you know, we were trying to do something that would help faculty and students,” he said. “The people who were really in a difficult position were the staff because they’re the ones that if they were gay, they could be fired. I didn’t know what to do about that.”

He didn’t know what to do until Ian Palmquist, a student who helped lead the Carolina Gay Association came to him with a mission: add sexual orientation to the university’s non-discrimination policy.

Wooten offered his help with setting up an appointment with the chancellor Paul Harden to make their case.

“I really just sat there and [Ian] did all the talking,” he said. “The Chancellor really didn’t say very much, but he said thank you very much, and he listened and he took all the data.”

That was it, until a couple months later, in the middle of the summer, when Wooten got a call. It was Ian Palmquist.

“He said, ‘Do you read the news? Do you read the Durham paper?’ And I said, no,” Wooten said. “He said, ‘well, maybe you should. Tomorrow, especially tomorrow morning.’”

The next morning, he picked up the paper and there it was. The headline read “Chancellor to add sexual orientation to university’s non-discrimination policy.”

“It was amazing,” said Wooten.

A lifetime of breaking down barriers, championing gay advocacy, and making lasting changes to the Carolina community later, Cecil Wooten wants you to know one more thing:

“You know, like being the chair of this committee for example, that was not courageous at all. Because you have to show courage when you have something to lose, and I didn’t have anything to lose,” he said. “I didn’t put myself in a dangerous situation. It was very easy for me to do. I’m not a courageous, heroic kind of person, but I did want to make something. I did want to make life for gay people a little bit better than it was when I grew up, or make a contribution to that. That’s why I did what I did.”

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.