When Hampton Dellinger saw the turf burns U.S. women’s soccer players were posting to social media, he decided that as an attorney he was in a position to do something about it.

The 2015 World Cup was the first World Cup to be played on turf, a plastic approximation of grass, instead of the real thing. Dellinger believed it was no accident that the first World Cup FIFA held on turf was a women’s event.

“You don’t have to be a soccer expert to know that natural grass is the preferred surface, and artificial turf is really a second-class surface,” Dellinger said. “At the end of the day, the only reason they [FIFA and the Canadian Soccer Association] tried something that the men never would have stood for was because it was the women’s World Cup.”

Players dislike turf because it changes the play of the game and because it puts players at more risk for injury. But despite a general consensus that turf is inferior, FIFA and the Canadian Soccer Association (CSA) decided to host the 2015 women’s World Cup on an artificial surface.

“There have been increasing financial ties between the artificial turf industry and FIFA,” Dellinger said.

However, Dellinger says FIFA had already planned all future men’s World Cup games up to 2022 on real grass.

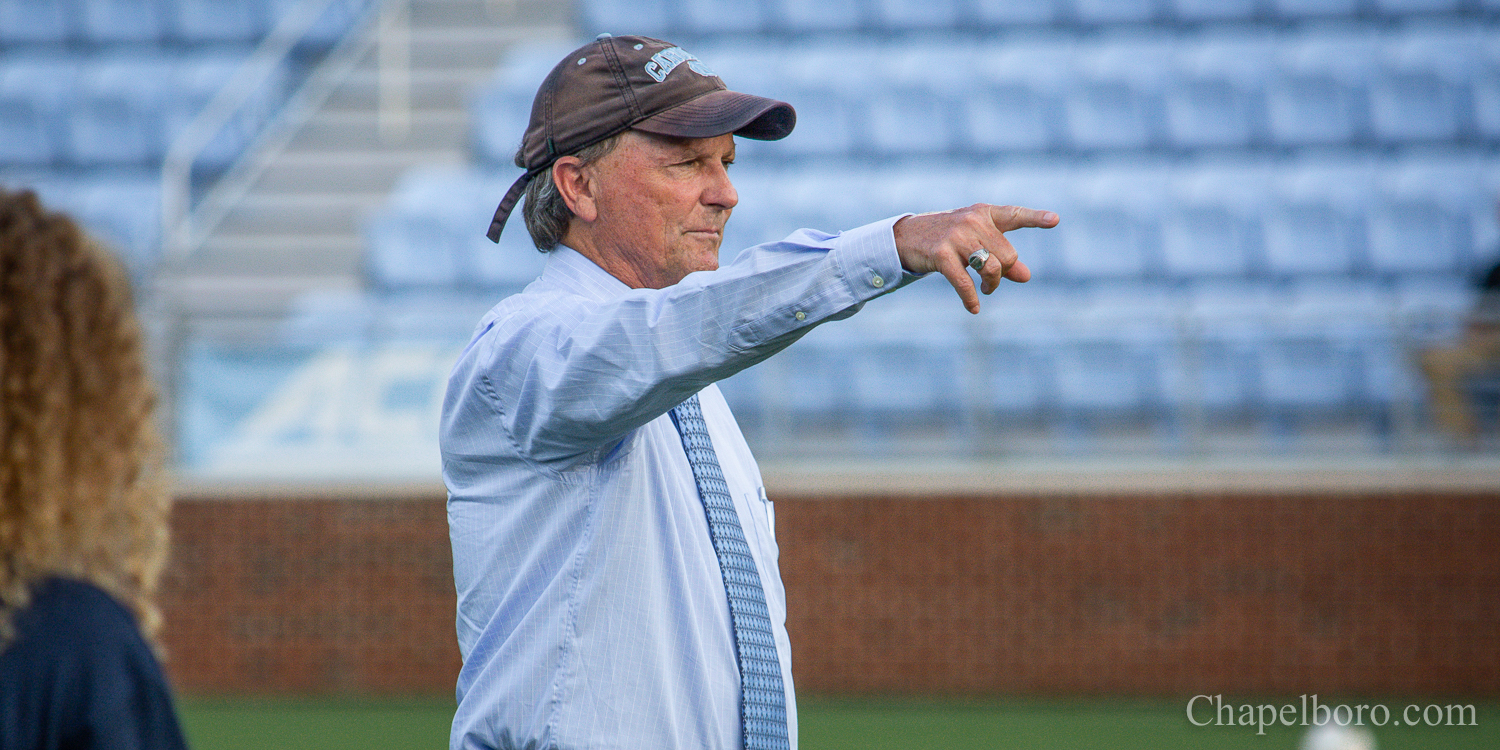

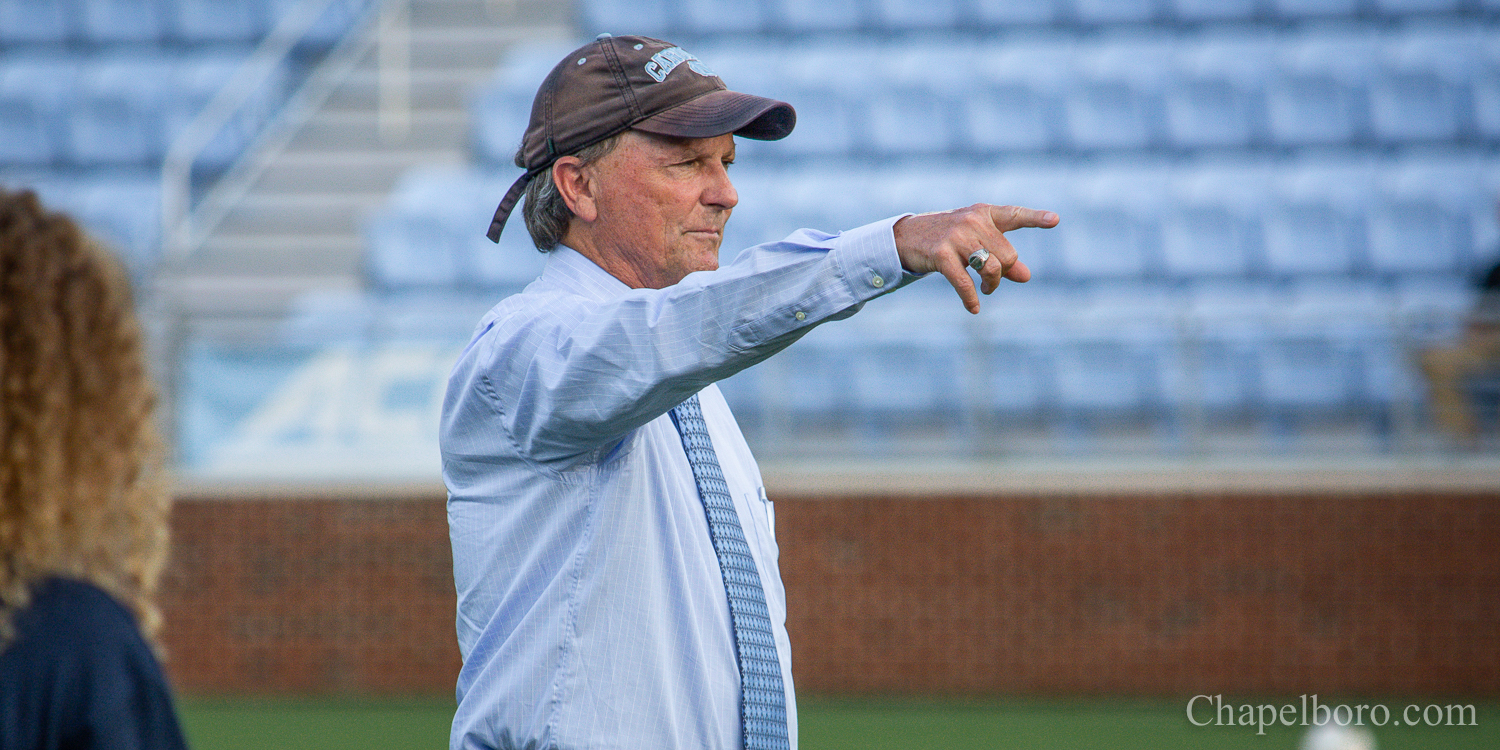

Dellinger, who used to cover UNC women’s soccer games as a commentator on WCHL, reached out to several UNC alumnae on the U.S. Women’s Team.

“I told them that if they wanted to challenge the discriminatory treatment based on their gender in court that I’d be willing to represent them for free, ” he said.

Several players on the U.S. team and other national teams worked with Dellinger to bring a gender discrimination case against FIFA and the CSA in the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal. However, the players withdrew their case in January because they needed to know what surface they would be playing on in the tournament.

“We got several favorable preliminary rulings,” Dellinger said. “But FIFA did everything they could to avoid a decision on the merits. And ultimately we could not get a trial date before the tournament started. And the players and coaches had to know what surface to train on because the differences are so dramatic.”

Dellinger says even though the lawsuit did not end in a ruling against FIFA or the CSA, he believes the suit pushed gender equality forward in the sports arena.

“FIFA committed to never put another women’s World Cup on artificial turf, they used goal-line technology for the first time in the women’s game after we raised it [as a point of contention], they increased the prize-money purse—although it’s still woefully insufficient,” Dellinger said. “So I think FIFA learned a lesson, and I think it raised consciousness about continuing gender discrimination in sports.”

Dellinger notes there are many more battles to be fought for gender equality in soccer, including the fight to bring in more women coaches.

“Many of the preeminent coaching positions are taken up by men in women’s soccer,” he said. “There need to be more opportunities for women in the coaching ranks and the administrative ranks.”

Related Stories

‹

Chapel Hill-Carrboro's Hope Renovations the Latest Local Nonprofit to Suffer Federal Funding CutsThe Hope Renovations CEO and founder vowed to "fight" against the termination of the nonprofit's federal grant funding over its equity goals.

![]()

On Air Today: International Women's Day Forum with Shimul Melwani, Susan Haws, Dee Gandhi and Rani DasiWith International Women's Month being recognized, 97.9 The Hill's Andrew Stuckey welcomes a quartet of local women leaders for a panel.

UNC Women's Soccer Earns 2-0 Win vs. Seton Hall Despite Weather DelayA lengthy weather delay did not throw off No. 5 UNC women's soccer on Sunday, as the Heels picked up their sixth win of 2024.

The First Woman To Run for President in Years in Senegal Is Inspiring HopeWritten by BABACAR DIONE and JESSICA DONATI Senegal’s only female presidential candidate may have little to no chance of winning in Sunday’s election, but activists say her presence is helping to advance a decades-long campaign to achieve gender equality in the West African nation. Anta Babacar Ngom, a 40-year-old business executive, is a voice for both […]

![]()

Stroman on Sports: The Global Sports Mentoring Program and WNBA PayDr. Deborah Stroman speaks with 97.9 The Hill's Brighton McConnell on Friday, April 28, about a trip to Benin and a new WNBA report.

International Women’s Day Events Highlight Gaps in Gender EqualityWritten by CIARÁN GILES Millions of people around the world planned to demonstrate, attend conferences and enjoy artistic events Wednesday to mark International Women’s Day, an annual observance established to recognize women and to demand equality for half of the planet’s population. While activists in some nations noted advances, repression in countries such as Afghanistan […]

![]()

Men, Women Split on Equity Gains Since Title IX, Poll ShowsWritten by COLLIN BINKLEY Ask a man about gender equality, and you’re likely to hear the U.S. has made great strides in the 50 years since the landmark anti-discrimination law Title IX was passed. Ask a woman, and the answer probably will be quite different. According to a new poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs […]

![]()

US Soccer Equalizes Pay in Milestone With Women, MenWritten by ANNE M. PETERSON and RONALD BLUM The U.S. Soccer Federation reached milestone agreements to pay its men’s and women’s teams equally, making the American national governing body the first in the sport to promise both sexes matching money. The federation announced separate collective bargaining agreements through December 2028 with the unions for both […]

Chanksy's Notebook: Take A Break, Coach!Anson Dorrance has earned a week off and he’ll probably get it. Can you believe the best women’s soccer conference in the country doesn’t let more than six teams play in the ACC tournament? If you look at the standings of haves and have-nots, you can see why. The Tar Heels are sitting in seventh […]

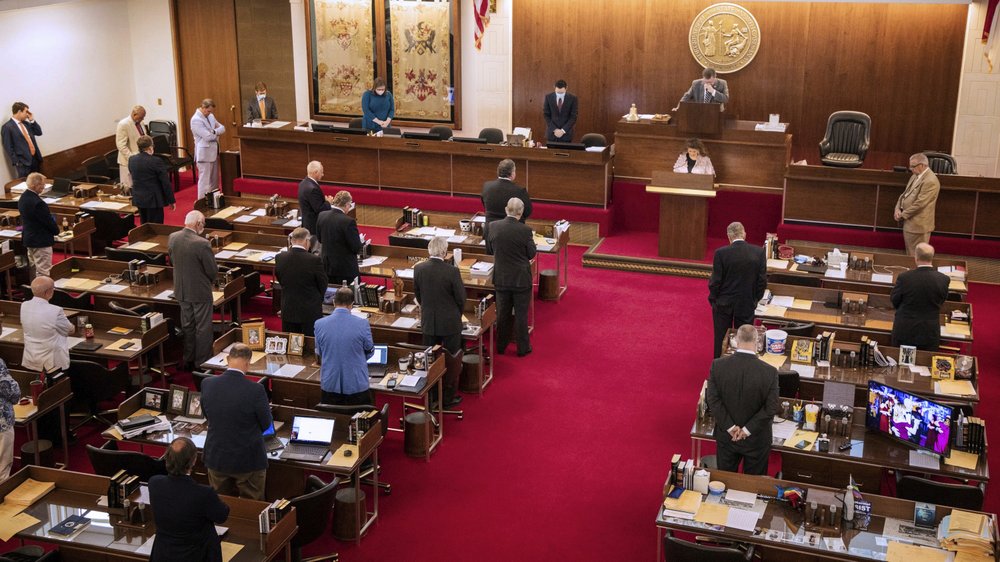

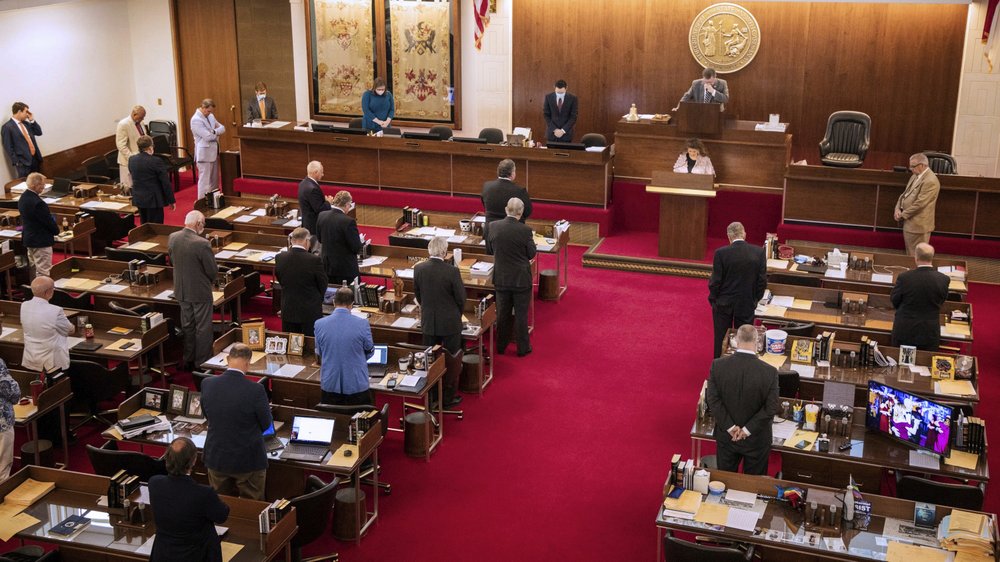

North Carolina Legislators Press Again For ERA RatificationEqual Rights Amendment supporters said Thursday it’s still important for the North Carolina legislature to ratify the proposal for the sake of fair treatment for all women, even as ERA’s future is being weighed by a court. General Assembly lawmakers and state and national ERA activists announced in an online news conference their redoubled efforts […]

›