(This story first appeared in the 1997 issue of Carolina Court magazine. It has been updated and edited for this weekend’s 50-year reunion of UNC’s title teams of 1967, ’68 and ’69.)

On January 4, 1967, in Winston-Salem, Carolina opened its milestone ACC season against Wake Forest. The score was tied at 74 and the Deacons had the ball with less than a minute remaining.

On January 4, 1967, in Winston-Salem, Carolina opened its milestone ACC season against Wake Forest. The score was tied at 74 and the Deacons had the ball with less than a minute remaining.

Bobby Lewis was dogging Wake guard Paul Long, trying to disrupt Long’s dribble with his spindly arms and legs. Finally, with the clock winding down and the Deacon fans on their feet and howling, Lewis flicked the ball away into the open court.

Retrieving it, Lewis pitched ahead to a breaking Larry Miller, who caught up to the ball just as he was going under the Carolina basket. With a move he had honed on the playgrounds of Pennsylvania, Miller spun the ball up off the left side of the backboard in one motion and kept running.

Still at full speed and looking back over his shoulder, he watched the ball glance off the glass and into the basket — then the muscular Miller collided with UNC Sports Information Director Jack Williams in the runway to the locker room. Williams went down like a load and Miller never broke stride.

He crashed through the locked dressing room door, taking it off at the hinges. Miller yelped once, then took off his uniform and hit the showers. By the time a wounded Williams walked in with Coach Dean Smith, Miller was slicking back his wet pompadour in the mirror.

For sure, it was going to be some kind of season for the Tar Heels.

“You have to say we were lucky that Rusty Clark and Bill Bunting were born in this state,” Smith said many times over the years, “because they and the others we recruited that year represented the turning point of our program.”

Clark, Bunting, Dick Grubar, Joe Brown and Gerald Tuttle – the famed Class of 1969 – gave Carolina the height and quality depth it lacked in Smith’s first five seasons. But their biggest gift to Carolina basketball was the freedom that allowed the reigning stars of the team to play where – and how – they would be most effective.

In 1967, when the Tar Heels won their first ACC championship and Final Four trip under Smith, it was the “L&M Boys” – senior Lewis and junior Miller – who really took the pressure off the highly touted sophomores. Not the other way around, as is popularly thought.

“The sophomores were put in the best possible position, because they were joining two fabulous players and didn’t have to be the stars right away,” says Larry Brown, retired Hall of Fame coach and Smith’s assistant in ’67.

Lewis and Miller, Smith’s first two marquee recruits, had played out of position up to that point in their college careers because they were needed on the front line.

A wiry leaper who regularly won dunking contests from kids almost a foot taller on the Washington playgrounds, the 6-3 Lewis had played the pivot for the UNC freshmen in 1964, power forward next to senior center Billy Cunningham in ’65 and small forward in ’66 when the bullish Miller moved up to the varsity. That’s the year Lewis set the single-game Carolina scoring record of 49 points against Florida State that still stands.

As a senior, he went outside to the big guard spot, unselfishly passing the ball more than shooting it. While setting up his taller teammates, he averaged six fewer shots as his scoring dropped from 27 points a game to 18.5.

“Bobby made the biggest sacrifice of all, no question about it,” Miller said 30 years later. “His game changed the most to accommodate the team, to make us better.”

The presence of the 7-foot Clark and 6-9 Bunting allowed Miller to move to the wing, where he was a triple threat. He could shoot his left-handed jumper, feed the post or take it to the hole. As a junior, he averaged 23 points a game and won the first of two straight ACC Player of the Year awards.

“When Coach signed Bobby and Larry, people took notice and said, ‘Whoa!”‘ Brown relates. “The pieces were falling into place, and I knew we were going to be really good in 1967 because I had coached the freshmen coming up. But I was kind of surprised we played so well together early.”

CHANGING OF THE GUARD

The previous year, when Brown was coaching his highly recruited freshmen, the varsity had fought its way to a 16-11 record while leading the nation in field-goal shooting, a precursor to all the years that the Tar Heels were at or near the top in that category.

Duke, which was on its way to a third Final Four in four years, had beaten Carolina twice during the regular season by a combined 25 points before the two teams met again in the semifinals of the 1966 ACC Tournament in Raleigh. Smith had the Tar Heels hold the ball, trying to force Duke’s big and slow front line to come out from under the basket. The Blue Devils stayed put and the Heels played Four Corners the entire first half, trailing 7-5 at the break.

“We’re sitting there, and he’s coaching like usual and the people are yelling, ‘C’mon, Smith, play ball!’ and throwing things at the bench,” Brown recalls. “Duke wouldn’t come out to play, and at one point I wanted to turn around and say, ‘He’s the head coach; if you’re going to throw anything, hit him.”‘

The Tar Heels inched out to a 17-12 lead before Duke rallied to tie the game and eventually win it on Mike Lewis’ free throw with four seconds left. “I didn’t want to play them a close game,” Smith said, “I wanted to win it.”

Miller, who had averaged more than 30 points and 30 rebounds a game his senior year of high school in Catasauqua, Pa., was not used to playing slow or losing. In fact, he and Lewis had lost to the ballyhooed freshman class in an open scrimmage before the season started, after which Brown had been scolded by his boss for creating so much spirit on the frosh team that it caused disharmony in the overall program.

But Miller welcomed the sophomores when they moved up to the varsity. “I recruited those guys when they visited, because I wanted to win,” he said. “We just had the chemistry and things jelled. It seemed like we could beat anybody we played.”

Carolina won 16 of its first 17 games, losing only to Princeton when Clark sat out with the flu. Among the victories was a 59- 56 upset of Duke in Durham, which signaled the changing of the guard in the ACC.

After five years of some narrow losses on the court, Smith’s luck seemed to be changing as well. With the score tied 56-56 and the clock ticking, he was trying to get a timeout when Clark hit Miller for the winning lay-up. “I can’t tell you how happy I am that nobody had seen my timeout signal,” Smith said after the game.

Duke coach Vic Bubas jabbed Smith, who had been hanged in effigy only two years before by critical UNC students. “If you hang me, do it close to the library,” Bubas said. “It’s more academic that way.”

Of course, Bubas wasn’t letting the mantle go without a fight, even after Carolina won the rematch in Chapel Hill by 13 points to clinch first place in the ACC standings for the first time under Smith.

Duke had been the media darling for years and when the teams met for a third time a week later in the ACC Tournament championship game in Greensboro, most members of the press still picked the Blue Devils to win.

Trying to keep the Heels loose and away from speculation that Carolina couldn’t beat Duke three times in the same season, Smith opened practice the week of the tournament by playing volleyball with them in Carmichael Auditorium. “I made sure Rusty Clark was on my team,” Smith quipped. “He’s some volleyball player.”

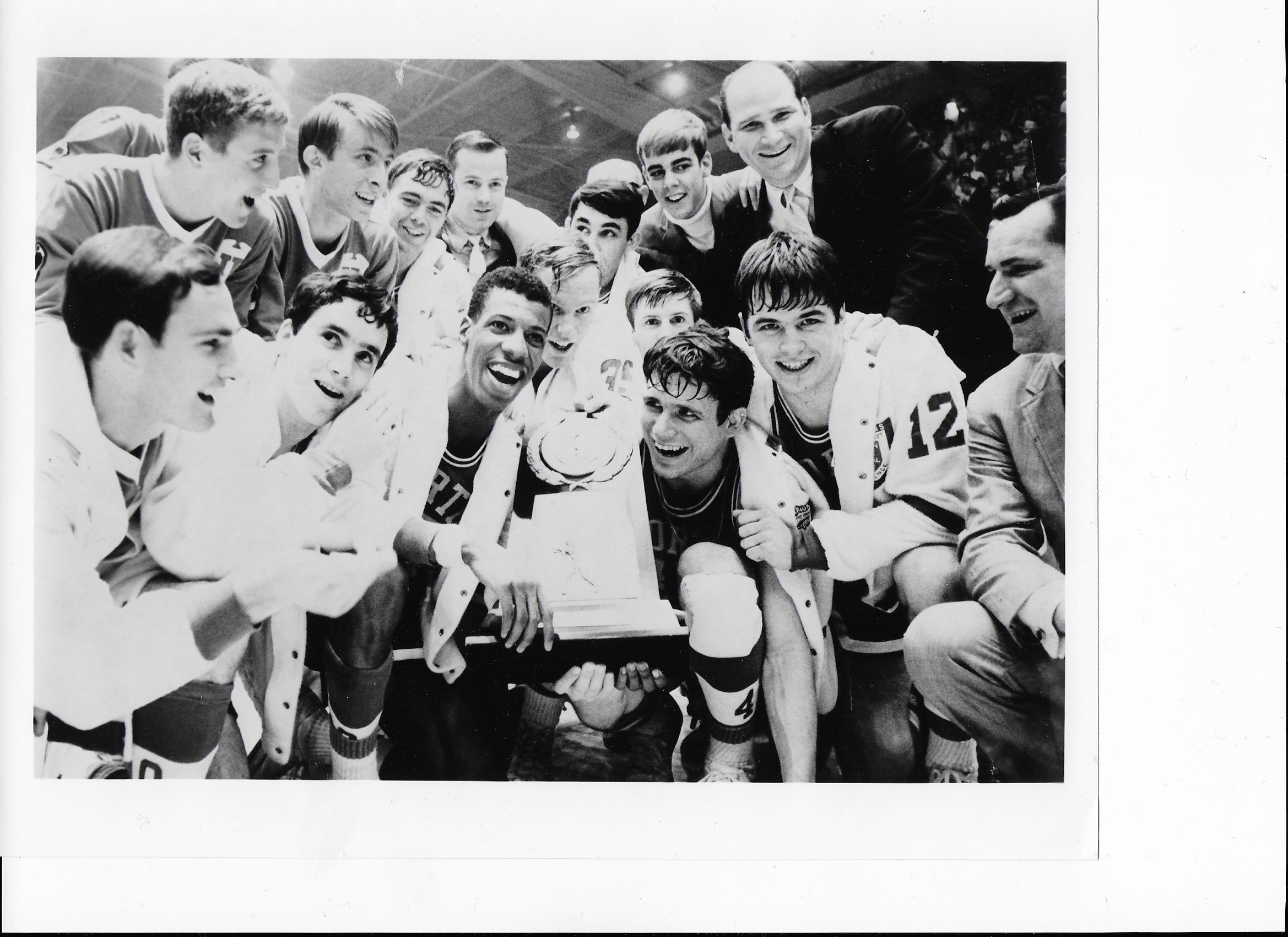

The Tar Heels beat Duke a third time, 82-73, earning the ACC’s only entry into the NCAA Tournament and ending the Blue Devils’ dominance in the league. It would be 11 years and three head coaches before Duke won another ACC championship.

“People today don’t understand what kind of pressure that was,” Miller recalls. “You had to win three games in three days or you weren’t going anywhere, no matter what you did in the regular season. I had to tell my parents, ‘You can’t come down here for the tournament.’ I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat. My stomach was in knots.”

Miller, who had been in a late-season shooting slump, hit 13 of 14 shots in the final for 32 points. “I remember the one I missed, too,” said Miller, who also had 11 rebounds against Duke. “It was from the corner, and when I let it go I thought it was in. It was just one of those games when I was in a frame of mind. I knew it was in the bag.”

Lewis scored 26 points, continuing his late-season surge after Smith and Miller had both told him to shoot more. “I haven’t been stupid enough to try to completely turn Lewis into a playmaker,” Smith had told Frank Deford of Sports Illustrated in February.

BREAKTHROUGHS

While he was becoming a high school All-American at St. John’s academy in Washington, Lewis gave little thought to attending Carolina. But midway through his senior year, he watched the Tar Heels’ nationally televised upset of Notre Dame in South Bend and pulled a letter from Dean Smith out of the hundreds he had received from college coaches.

After Smith went to watch him play later that season, Lewis agreed to visit Chapel Hill with his mother, Virginia, a former semipro basketball player who had once made 35 consecutive free throws in games.

“He and his mother went out to dinner with me,” Smith told Ronald Green of the Charlotte News in 1967. “His mother told me later that he pretty much made up his mind that night that he was coming. I wish he had told me. He kept us in suspense for a long time.”

Lewis spent much of his weekend with Cunningham, the All-American who Smith had inherited from Frank McGuire’s program. In 1965, sophomore Lewis and senior Cunningham led a late-season surge after Smith had been hanged in effigy, the Tar Heels won eight of their last 10 to begin a 39-season streak of top three finishes in the ACC.

Then Lewis blossomed into a full-fledged star as a junior, the year Carmichael Auditorium opened and the year he set the school scoring record against Florida State. He scored more than 27 points a game to lead the ACC while shooting 53 percent from the floor. With Miller, who averaged 21 points, having moved up to the varsity, the first references to the “L&M Boys” were made in local newspapers.

Of the obvious connection to the Liggett & Myers Company on Tobacco Road, Deford was to write in Sports Illustrated the next year: ” … if Lewis is the soft pack, Miller is the hard, flip-top box.”

Compared to the skinny, 175-pound Lewis, Miller was a brute at 200 pounds of arms, chest and legs. He was a true man-child, having given up schoolboy gangs and stealing hubcaps to take up basketball in his teenage years. He lifted weights before it was fashionable for basketball players, and he had played for Allentown in the old Eastern League against semi pros twice his age.

Pressured long and hard by Bubas to join the Duke dynasty, Miller had been swayed by his weekend in Chapel Hill where he cruised the town with Tar Heel stars Cunningham and Lewis. “They asked me if I wanted to go to the movies or go to a party,” Miller remembers. “I said to them, ‘Are you kidding?'”

The words of former UNC assistant coach Kenny Rosemond, who had doggedly recruited Miller and his father, Julius, rang true during and after the visit.

“You know, Larry,” said Rosemond, who died in 1993, “the saddest thing is if you went to Duke, you’d be going all that way and you’d still be five minutes from heaven.”

Miller had always had Carolina on his mind, or at least in his memory, since listening as an 11-year-old to the radio broadcast of the Tar Heels’ triple overtime win over Kansas for the 1957 national championship.

Grown up to become the best high school player in the country in 1964, Miller had been swamped by scholarship offers – and more from some schools. “There was a lot of money and things,” he says, “but I wasn’t interested in that. I had a family that worked hard and had high ethics.”

Miller admits being left in tears at the Holiday Inn at Allentown when Bubas took out the grant-in-aid and handed him the paper and a pen. “I was crying because Vic Bubas was a wonderful person and I really liked him and Bucky Waters, his assistant. It was a real emotional thing,” sighed Miller, who called Bubas on his 91st birthday this week.

He told the Duke and UNC coaches he would invite the “winner” to his high school graduation. “I called Coach Smith, and he came up there,” Miller said. “I was excited to be going to the ACC. Another ACC coach had told me that wherever I went, the pendulum would swing toward that school. It was basically a coin flip between Duke and Carolina.”

Indeed, but it would take a couple of years. By that time, Miller had become almost a folk hero in North Carolina. “It was like ‘Richard Petty for President and Larry Miller for Vice President,”‘ he said. “All the attention was a little embarrassing.”

Miller was more flamboyant than Lewis and, nonetheless, relished the super star role. He drove a hot convertible and made the rounds at fraternity parties, often with a Southern beauty on his arm.

“As captain my senior year, I told the guys we were going to work hard on the court, but after the games we were going to enjoy ourselves,” he said, adding with a laugh, “they all went along with it.”

One legendary story about Miller is the time he smuggled a case of beer onto the team bus after the Tar Heels had won big at Virginia. “I’m not sure I should tell this story, but when we stopped to eat on the way back from Charlottesville,” he said, “I paid a guy in the kitchen of the restaurant to put the beer on the bus while we were inside eating. The coaches never knew a thing.”

Lewis had deferred to Miller’s immense presence in 1967, sacrificing the ball to feed his teammates and play the best defense of his career.

“Before this year,” Lewis said back then, “I never went into a game when I didn’t assume I would score 20 points. I expected that of myself. If I only got 14, I’d go crazy and start worrying what went wrong.

“I always wanted to win and score points. But I wanted to prove something … to show I could do everything else. I am really enjoying this season.”

THE PLAYERS

Lewis, ironically, has not returned to Chapel Hill often, but he still follows Carolina basketball from his home in Edgewater, Md. “Having been a Tar Heel basketball players means the same to me today as it did 50 years ago,” says Lewis, who worked for the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. ” … when I have been part of a conversation about UNC and Dean Smith, I have felt a sense of envy from others when I mentioned I was a graduate and part of this coach’s great program.”

Lewis’ personal best as a senior was during the NCAA Eastern Regional in College Park, near his home town, when he won the MVP after leading the Tar Heels over Princeton, avenging the earlier loss, and Boston College. Afterward, Lewis’ sister threw a giant “Final Four” party for the team and some Carolina fans.

Miller, a two-time All-American and member of the college basketball Silver Anniversary all-star team, remained close to Smith and Tar Heel basketball for almost 40 years. “I read where Michael Jordan calls Coach his surrogate father,” Miller says. “I kind of feel the same way, now that my father has passed away. I would call the basketball office at least once a month and talk to Coach Smith, or whatever coach was there.”

After living in Raleigh and Virginia Beach, Miller returned to Catasauqua to care for his ailing mother until she passed away. He stayed there and still has many friends from his high school days. Like Lewis, who played a few years with Golden State in the NBA, Miller had a short-lived career with three teams in the old ABA. He owns the ABA single-game scoring record of 67 points when he played for the Carolina Cougars.

“Two nights after scoring the 67, my house in Greensboro burned to the ground,” Miller says. “My two dogs died while they were sleeping under the bed, and I had to break a window to barely get out myself. At that point in my life, material things became immaterial.”

After making the All-ACC team twice, and being named ACC Player of the Year and ACC Tournament MVP twice, Miller soured on the selfish play of pro basketball. His game was one of transition and team work, bang the boards and muscle inside, set picks and hit the open jump shot. He made his points the old fashioned way.

“If we had made all of the money they make today, I guess I would have kept playing,” he says, “but I was disillusioned with the way the teams played. I could always play defense, but no one seemed to care. The coaches only wanted guys who could jump, get their own shot and shoot from outside.”

Clark, who still has the single-game UNC record of 30 rebounds against Maryland, turned down pro basketball to attend medical school and is a wealthy thoracic surgeon in his home town of Fayetteville. He is a frequent visitor to Chapel Hill, his thinning red hair clearly visible over the crowds on the concourses of Kenan Stadium and the Smith Center.

Bunting, from New Bern, played a while in the ABA and went on to work for a government housing agency in Raleigh. His college career improved steadily each season, underscored by the relatively amazing improvement of his field goal shooting from 43 percent as a junior to 60 percent as a senior – when he took 164 more shots than the previous season and made first-team All-ACC.

The popular Grubar also had a short stint in pro basketball, but the knee injury he suffered in the 1969 ACC Tournament finals never healed enough for him to keep playing at the same level. The quarterback and matinee idol of the Tar Heels, Grubar returned to North Carolina after five years as an assistant college coach to enter private business. He has homes in in Greensboro, where he served on the City Council, and Florida.

Joe Brown entered private business in Raleigh, as did Gerald Tuttle in Hickory. A sixth sophomore that season was Jim Bostick, who transferred to Auburn as a junior and worked as a computer analyst in Richmond.

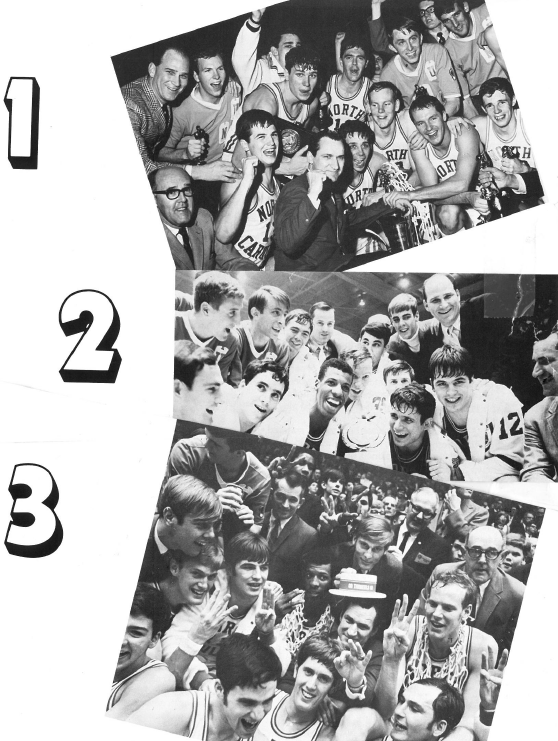

The Class of 1969 remains the only one in ACC history to win three straight regular season titles outright and three consecutive ACC Tournaments. With Charlie Scott replacing Lewis in 1968 and becoming the star of the 1969 team after Miller graduated, the Tar Heels compiled a three-year varsity record of 81-15, with five of the losses coming in three trips to the Final Four. Their ACC record was 45-6, never losing to N.C. State, Wake Forest, Virginia or Maryland.

Also on the 1967 Tar Heels were seniors Tom Gauntlett, Mark Mirken and Donnie Moe. Gauntlett entered private business in Dallas, Mirken became an attorney and Moe a stock broker.

The other juniors with Miller were Ralph Fletcher, a retired stock broker in New York, and Jim Frye, who was a high school administrator in Illinois.

THE LEGACY

The signs in Chapel Hill read, “Remember ’57 in ’67!”

When the Tar Heels advanced to the Final Four in Louisville, it was 10 long years since they had been there to complete the legendary undefeated season of 1957. “McGuire’s Miracle” had so fixated the state that Smith had an awful time digging his way out of Frank McGuire’s shadow.

Now, after taking his own team to the last weekend of the season for the first time, Smith was again being compared to his colorful predecessor. Fortunately, UNC fans were just happy to be back in the Final Four, and they weren’t devastated when their team played poorly and lost the national semifinal game to Dayton.

“Coach Smith zoned early against Dayton because he was worried about how to stop their athletes,” recalls Larry Brown. “We got the lead and then went back to man-to-man. After they beat us, Coach said, ‘Larry, we might have been better off if we had stayed in the zone, but I’m not a zone coach.”‘

Miller, for one, doesn’t think it would have made any difference. He was the Tar Heel trying to stop Dayton All-American Donnie May, who scored 34 points. “It was my fault because I was guarding him,” Miller says. “I ran into him years later and told him, ‘You just beat the crap out of us.’ He was hitting 25-footers and he was 6-7!”

In the third-place game against Houston the following night, Smith let his seniors play longer than normal as a reward for sticking it out after the younger stars moved into the lineup. Another lopsided loss ensued, but another Carolina party broke out after the game.

“After we lost the game, our fans took over Louisville, yelling ‘We’re Number 4,'” Brown remembers. “I knew then that things had changed. There was so much appreciation for what had been done. Something special happened.”

Smith brought the 1967 team, plus the ’68 and ’69 Final Four members, back to Chapel Hill for a grand reunion in 1998. Now Roy Williams has done the same to celebrate another anniversary of the famous Three-Peat.

After all, it’s a place the L&M Boys started building 50 years ago.