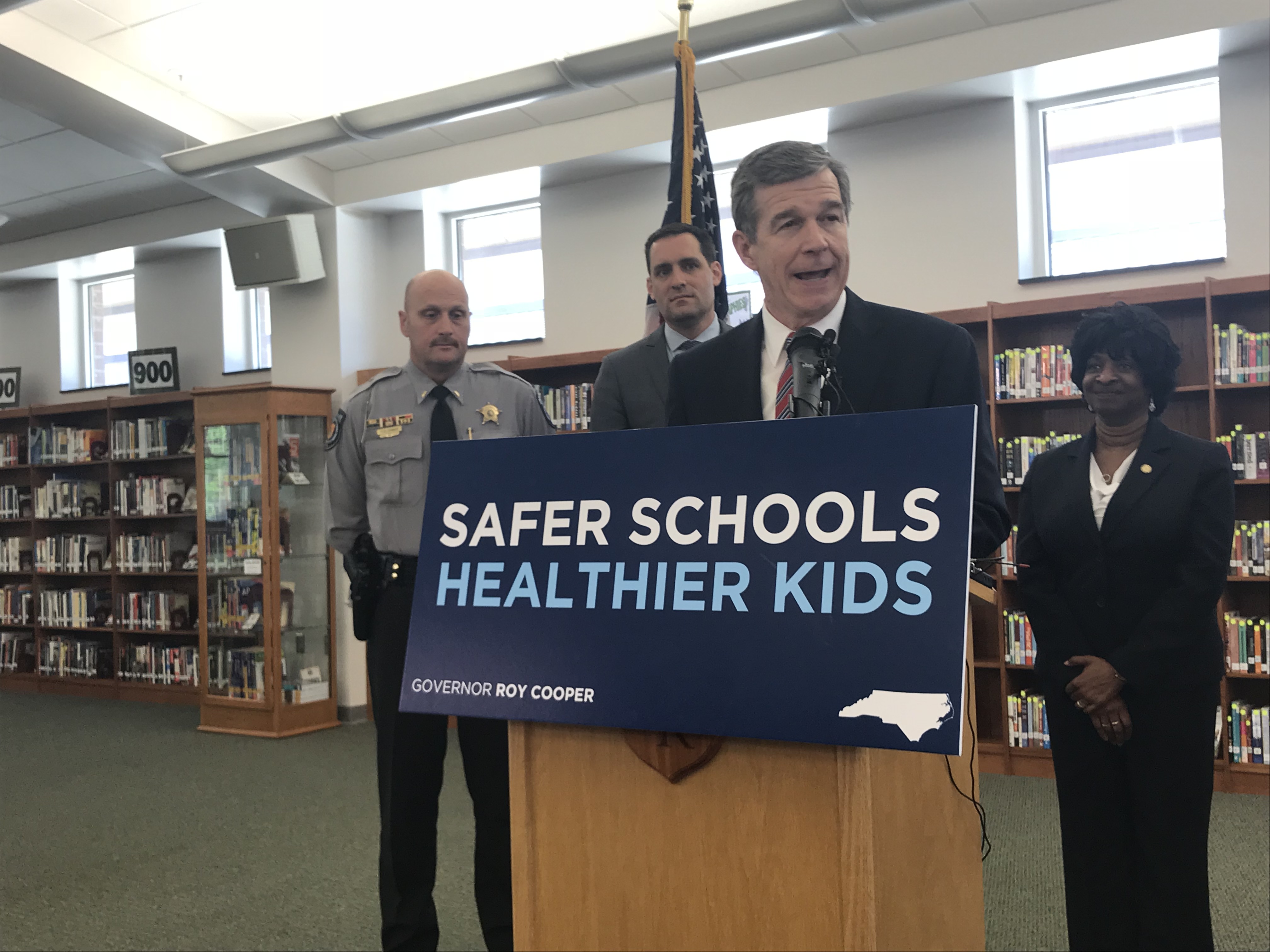

North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper appears to have “improperly used the authority and influence of his office” to pressure natural gas pipeline builders to agree to a $57.8 million mitigation fund under his control, private investigators reported Wednesday.

The report’s authors, however, found no evidence that the Democratic governor personally benefited from the fund. Cooper’s office slammed the report as “full of inaccuracies and contradictions.”

A Republican-controlled legislative committee hired the former federal agents a year ago to review the January 2018 side deal between the governor’s office and utilities working on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

Cooper’s environmental department announced a key water permit had been issued the same day the mitigation fund “memorandum of understanding” with the governor’s office was unveiled.

The money the pipeline operators — Duke Energy, Dominion Energy and others — had agreed to pay was intended for environmental mitigation, renewable energy and economic development projects along the proposed pipeline’s route in eastern North Carolina.

Cooper and his aides have said repeatedly that the mitigation package wasn’t a prerequisite for the permit. But Republicans, unconvinced, turned to Eagle Intel Services to investigate, at a cost of $83,000.

The report’s authors said their investigation didn’t focus specifically on whether crimes happened, and an investigative agency with more powers could potentially determine that. But the report said “the information suggests that criminal violations may have occurred.”

Members of the oversight committee peppered the firm’s three investigators with questions about the report for 90 minutes Wednesday. But the panel lacks power to take direct action in response to the findings.

“I’m deeply concerned that the governor’s office interfered with the objective permitting process in an improper manner,” said Rep. Dean Arp, a Union County Republican.

But Cooper’s office said the 82-page report is wrong and clearly ignores “inconvenient facts.”

“The report even concedes that the permit was done properly, that Duke believed the permits weren’t dependent on the fund or the solar settlement, and that the governor did not benefit,” spokesman Ford Porter said in a statement.

Cooper and his aides have said the memorandum was drawn up the way it was because they didn’t trust the GOP-dominated General Assembly to spend the money for its intended purposes, and pointed to a March 2018 law as proof.

Lawmakers agreed to essentially intercept the mitigation money and give it to school districts along the route. The state has never seen the money, however, because legal challenges have delayed construction on the 600-mile pipeline through West Virginia, Virginia and North Carolina.

Somewhat similar mitigation funds had been agreed to in West Virginia and Virginia. Duke Energy executives had said greater fuel access in eastern North Carolina meant a similar fund wasn’t required in North Carolina, the report said. But in late 2017, local businesses, Cooper’s office and his Department of Commerce became concerned the pipeline wouldn’t create the jobs and economic development that pipeline developers predicted.

Duke Energy CEO Lynn Good said Cooper told her during a November 2017 private meeting that there was “balking” at the Department of Environmental Quality over issuing pipeline permits and environmental justice issues, the report said. Good, who was interviewed by the investigators, said Cooper asked her “to consider the creation of a fund” for economic development by the end of December. Duke had wanted to get the permit by the end of 2017 so they could begin tree removal.

The mitigation fund initially had been set at $55 million, the report said, but Cooper asked Good in a mid-January 2018 phone call to raise it to $57.8 million — the same amount Virginia was to receive — and Good agreed. The permit’s issuance and the mitigation fund were announced separately on Jan. 26, 2018.

Cooper “continued to use his authority and influence to delay the ACP permitting process until the ACP partners agreed to increase the fund amount to $57.8 million,” the report said. Good also said Duke Energy also agreed to work with the solar industry to resolve a rate disagreement. That deal was announced the week after the permit and fund were announced.

“Certainly, the facts that were presented to us, yes, it does show a connection,” investigator Kevin Greene told lawmakers during the hearing.

But Good told investigators that the ACP builders and Duke Energy didn’t believe the mitigation fund and the solar settlement had any bearing on the water permit being issued. The pipeline was entitled to the permits, according to Good, and “Duke did not and would not pay for permits,” Good was quoted as saying.

Speaking at a pre-Thanksgiving turkey “pardoning,” at the Executive Mansion, Cooper told reporters “the facts on our side.”

“We were fighting for economic development in eastern North Carolina,” Cooper said, adding the he “absolutely” did not make the final decision on any permit but his environmental department did. That would run counter to what a Duke lobbyist said a Cooper adviser told her in December 2017, according to the report. Cooper’s office said Wednesday that the lobbyist was mistaken.