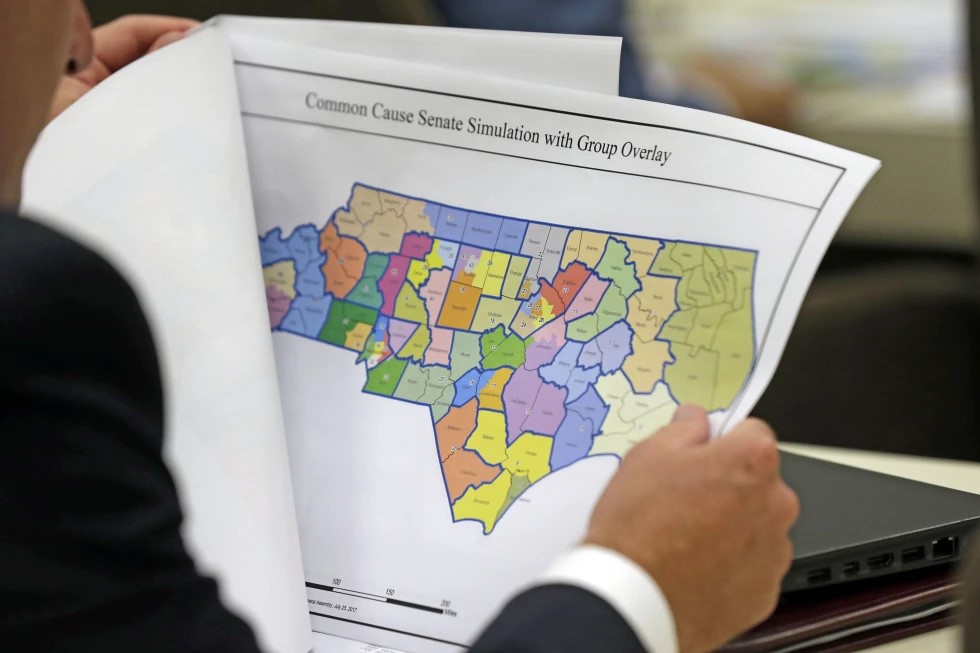

Drawing the congressional map in North Carolina has been a topic of debate, in conversation and in courtrooms, for decades.

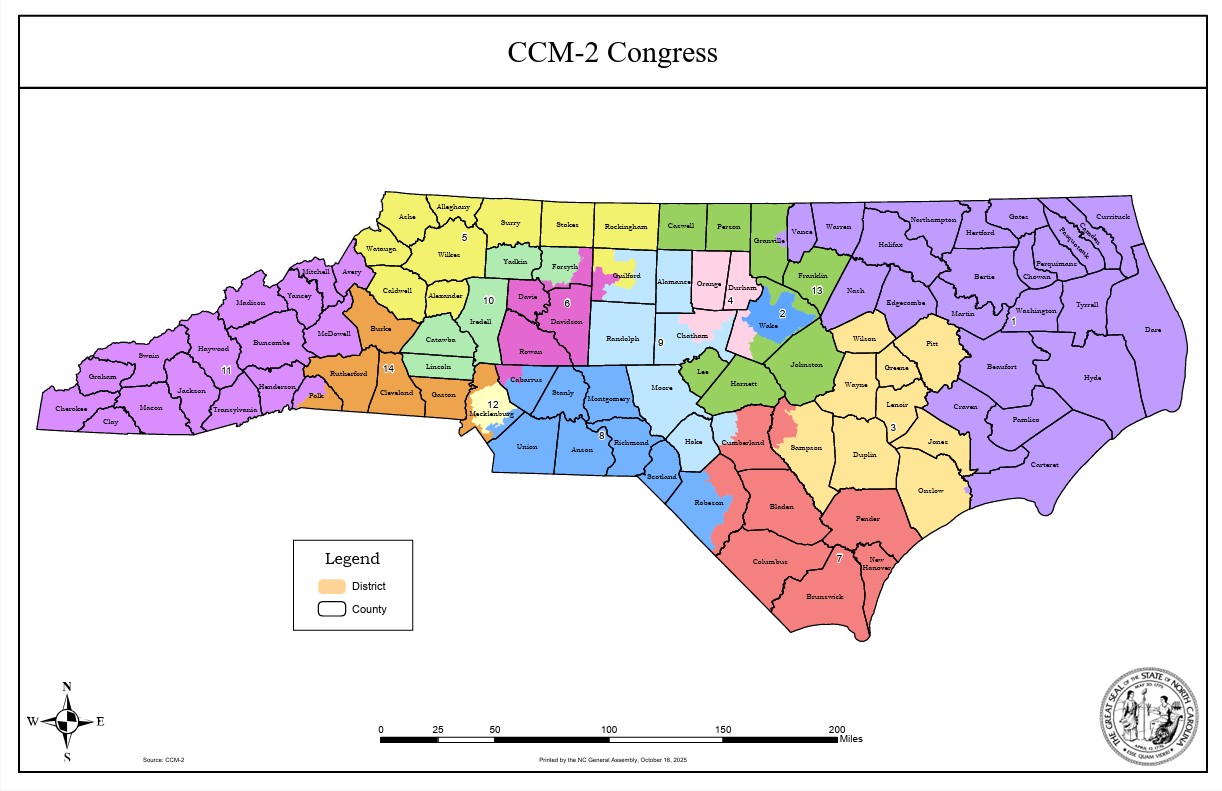

The latest rendition of the North Carolina congressional district map is constitutional, according to a State Supreme Court ruling. State Republican lawmakers are responsible for the latest depiction of the districts; the GOP drew the map in 2011, after the last census in 2010. The legal challenge to the map’s constitutionality may not be done, as an appeal to the US Supreme Court is likely. There have been 27 judicial interventions in North Carolina’s drawing of congressional districts in the last 30 years, according to the NC Coalition for Lobbying and Government Reform.

Listen to the full segment here:

Jane Pinsky is the director of that organization; she says the challenge to the previous district drawing was followed by a particularly long legal battle, “The 2001 redistricting finished with a lawsuit that was decided in 2009.”

Pinsky says partisan drawings have been the standard in the Tar Heel state. And drawing the map for political gain is technically legal, according to court rulings.

Kareem Crayton is an Associate Professor of Law at UNC; he says that the close ties between race and politics in North Carolina lead to a challenge that most states do not face.

“Is there a way to tease apart this purported concern with race and perhaps hyper-partisanship,” he asks, “in a way that makes a lot of sense to people and, frankly, keeps both the Democrats and Republicans at bay?”

One suggestion has been to look to other states as a model, one in particular being Iowa. Pinsky says their formula is developed by a professional staff and then voted on by legislators.

Professor Crayton adds that many states are looking at Iowa’s model, but there are some inherent issues.

“Iowa, by comparison, is not as ethnically and racially diverse as most other states in the union,” he says. “Certainly among states in the South, where there is a significant African-American population in the state electorate.”

Some states have taken pieces of the Iowa formula and molded it to fit their state’s needs. Ohio has created a new system for drawing their districts, which involves an independent commission drawing the map.

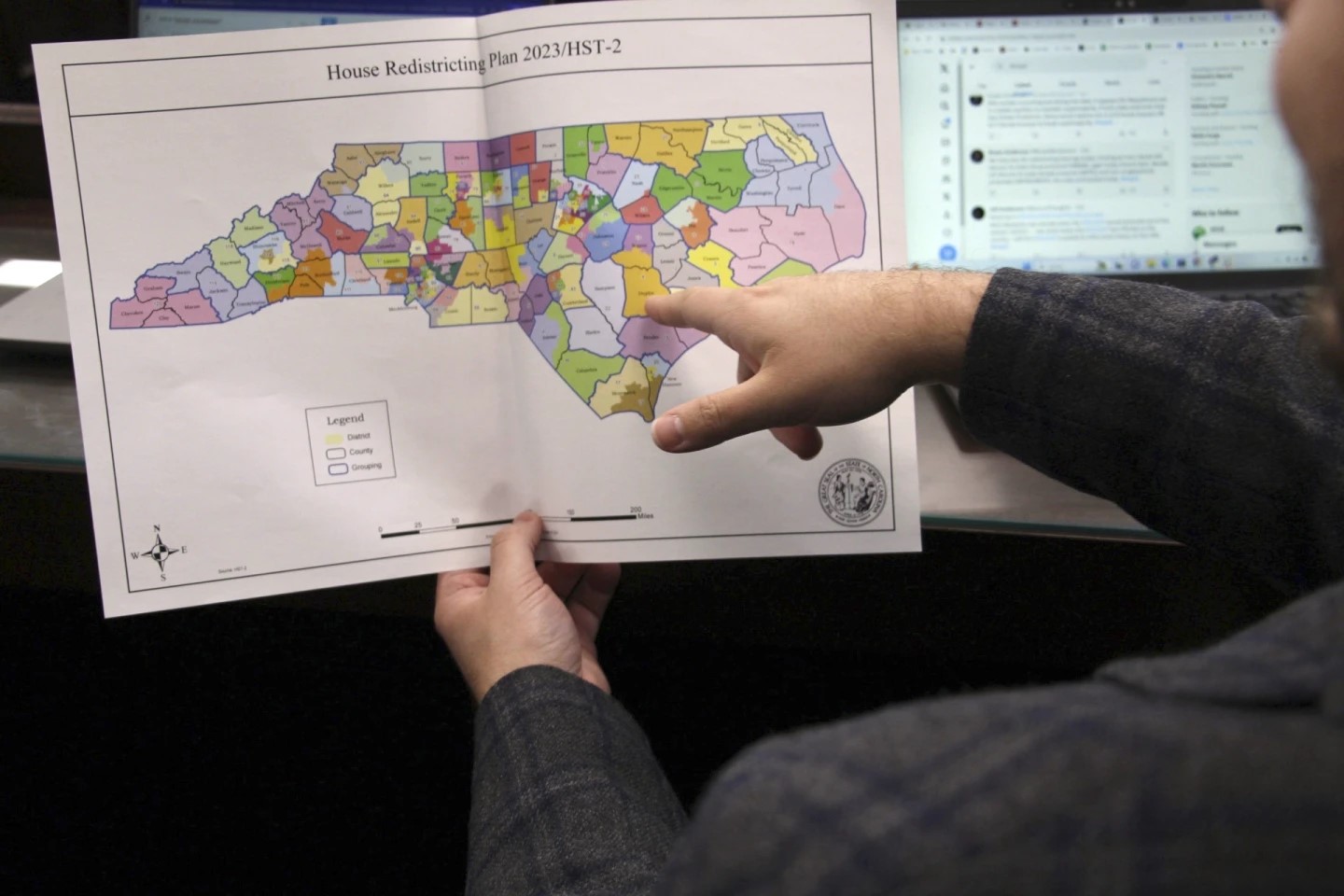

Pinsky says to get to a point where North Carolina deviates from the current formula of the dominant party having ultimate power over the drawings – and the seemingly endless legal battles associated with that –legislators will have to give up their power for drawing the congressional map.

She adds that state house lawmakers have agreed to a plan to move toward a new system on multiple occasions, but senate legislators have refused to move on the plan while litigation is ongoing.

Professor Crayton says that some other states have been successful in taking the power of drawing the map out of the legislator’s hand and allowing the citizens to decide on the congressional districts through a voter referendum.

“When the public gets mad enough and organized enough,” he says, “there usually is an effort to think creatively about a system that can stand any alternative.”

The possibility exists that the lawsuit over North Carolina’s congressional map could be combined with a similar suit out of Alabama and be brought before the US Supreme Court.

Regardless of any legal decision, the next time the lines will be put on a map of the Tar Heel state will be in 2021.

Whether that drawing will remain under our current system or if it will be subject to new – possibly less partisan – guidelines, remains to be seen.