A new study from Duke University suggests the interaction of two structures in the brain may help predict one’s risk of problem drinking.

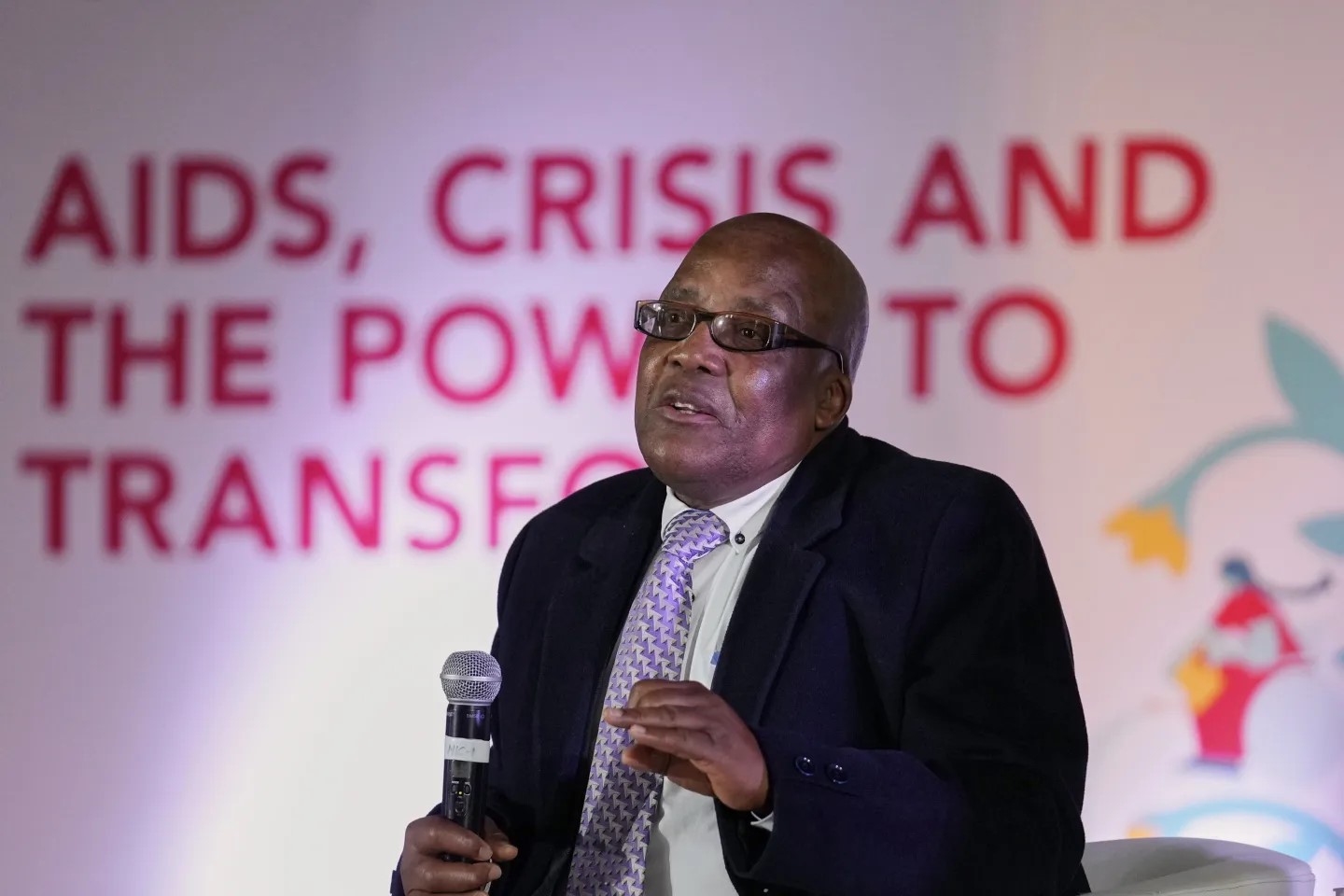

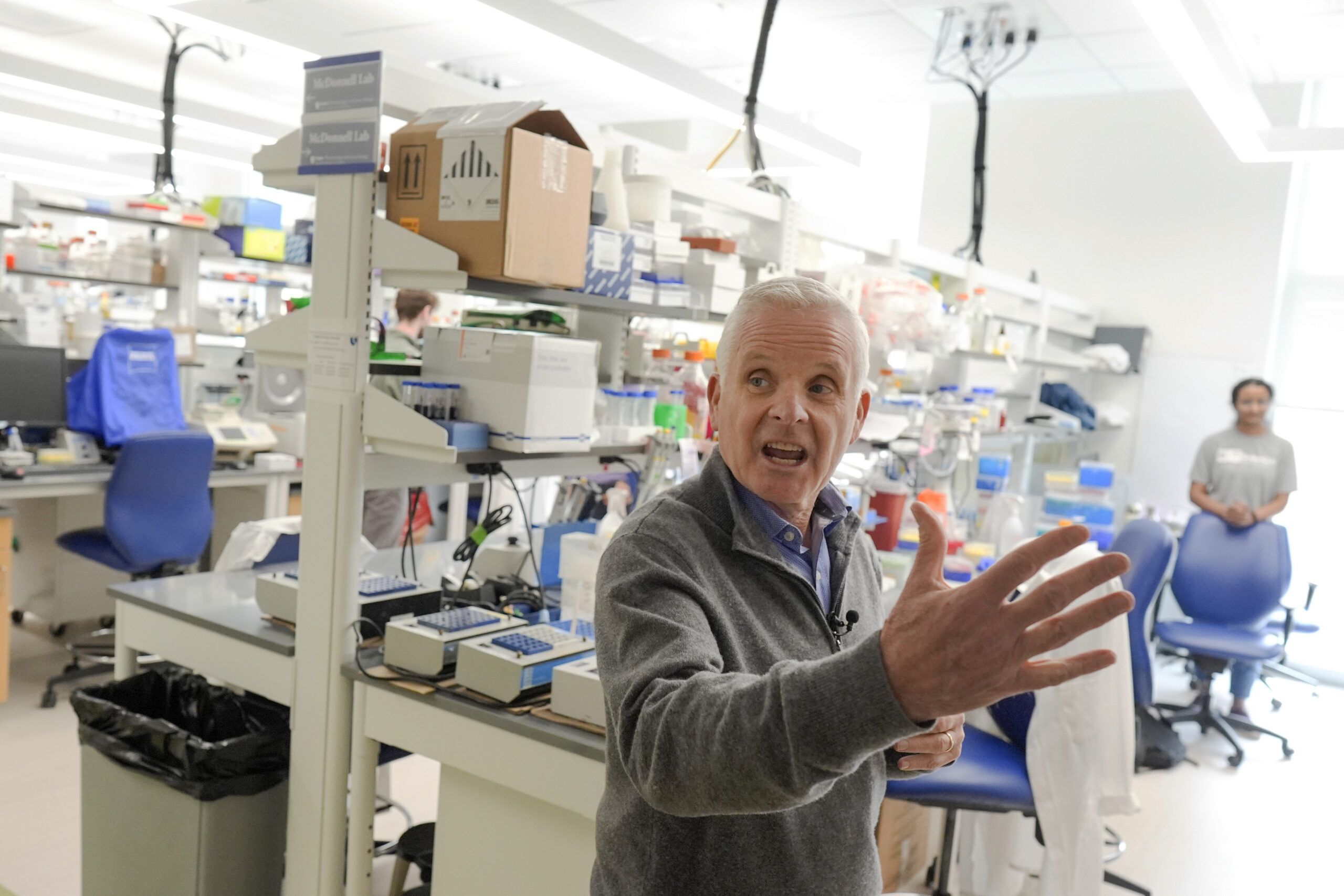

College can be a stressful time. For many young people, it’s the first extended period away from home, academic expectations are high, and students are constantly thrown into new social situations. Students have been known to binge drink in order to cope. But Ahmad Hariri, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, says some students’ brains may put them more at risk than others for these behaviors.

“A combination of an individual’s brain response to threat and brain response to reward interact to tell us something about how likely the individual may be to develop problem drinking when they’re stressed out,” Hariri said.

Hariri’s study measured function in two parts of the brain: the ventral striatum, or VS, and the amygdala.

“These are kind of core deep-brain structures,” Hariri said. “Really every animal with a backbone has essentially an amygdala and a ventral striatum, and they do very similar things.

“The VS is there to help individuals recognize reward—‘This is a good thing, how did I get good thing, and how can I get it again?’ The amygdala on the other hand is ‘This is a bad thing. I don’t want this to happen again. How can I avoid this bad thing in the future?'” Hariri explained.

In Hariri’s study, it turned out that when one of these parts was working harder than the other, the undergraduate study participants were more likely to engage in excessive drinking.

“As a whole what we find is that imbalance is generally associated with negative outcomes—with high risk-related behaviors,” Hariri said. “That’s just the starting point. It’s going to be more helpful to understand how the different types of imbalance lead to the same problem.”

Hariri believes that when the amygdala is working harder than the VS, it produces higher levels of stress. At the same time low VS activity may make it harder for people to enjoy pleasurable activities.

“This is the affect of depression where people don’t want to go out with friends,” Hariri said. “People don’t want to go to movies, they don’t want to read books—they just want to lie.”

Feelings of depression from an under-active VS, coupled with stress from an overactive amydgala could lead people to drink. But Hariri says the opposite imbalance—an overactive VS and an under-active amygdala—were also associated with alcohol abuse.

“When you don’t have a strong amygdala signal, which helps you recognize danger, and you have a relatively stronger signal from the ventral striatum, which is motivating you to seek out enjoyable things, you also see problem drinking,” Hariri explained. “And here, we were able to link this opposite pattern of imbalance towards higher levels of impulsiveness.”

Hariri notes the interaction of these structures is only one small part of understanding how the brain affects one’s risk of dangerous behaviors. But he hopes further research will allow healthcare providers to identify those at risk before they turn to alcohol as a coping mechanism.

“Now that we have these two patterns of risk-related brain function, if continued work proves that these are in fact really important for understanding risk, can we develop a panel of genetic markers that reliably tell us if someone is going to show imbalance A or imbalance B?” Hariri asked.

Hariri’s study is part of a larger on-going project called the Duke Neurogenetics Study. Researchers began the project in 2010 to understand how the brain, genetics and the environment are involved in mental illnesses.