Bill Dooley had some big wins at UNC from his very first season.

When Dooley took over Carolina football in 1967, he ran off about half of the squad he had inherited. Spring practice was more like boot camp, and those who survived it could stay around and play for the Tar Heels in the fall. Those who couldn’t cut it turned in their pads and spent their autumn Saturdays watching from the stands.

And although Dooley’s thin squads won only five times his first two seasons, Carolina did whip Duke twice in the last game behind quarterback Gayle Bomar and upset nationally ranked Florida in a driving rainstorm in Kenan Stadium. The Tar Heels weren’t that great at football but they were tough as nails, and every opponent knew it.

In 1969, Dooley unleashed a tailback named Don McCauley on the ACC, and McCauley wound up the school’s all-time leading rusher. He is still Carolina’s top running back among three-year players with 3,172 yards, 279 of them in his final home game against Duke when McCauley scored five touchdowns.

That 1970 season was Dooley’s first winner and his first bowl team. The Tar Heels lost to Arizona State in the old Peach Bowl that began under clear skies but ended in a near blizzard. The next year, Dooley won his first of three ACC championships and lost to Georgia and big brother Vince in the bruising Gator Bowl, 7-3. They repeated as ACC champs in 1972, going 11-1, losing only to Ohio State, which discovered a freshman running back that day named Archie Griffin.

Carolina posted six winning seasons in Dooley’s last eight years before he went to Virginia Tech as football coach and athletic director. By then, every ACC school that did not have a tough guy for a football coach had either hired one or fallen to the bottom of the league. Dooley brought a Southeastern Conference mentality and winning tradition to UNC; his 11-year tenure was followed by 10 under Dick Crum and 10 more under Mack Brown, both of whom also had mostly winning teams and played in bowl games regularly.

It was after Dooley retired from coaching and split his time between Raleigh and Wilmington that his image softened and he became beloved by his former players. All the Tar Heels who had survived Dooley’s boot camps were now men in their coach’s eyes. Every one of them still living will be at Dooley’s memorial to say goodbye, and thanks, to the old trench fighter, their coach and friend.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe:

Related Stories

‹

Tributes Pour In After James Spurling, Director of Kenan Stadium, Dies at 68James Spurling, who served as the Director of Kenan Stadium and the Kenan Football Center in the heart of the UNC campus since 2006 and had been a Chapel Hill staple for many years prior, died Thursday. He was 68 years old. Tributes flooded in from across the Chapel Hill and UNC sports communities following […]

Financial Report Shows UNC Athletics Operated at $15 Million Deficit in 2024-25 YearThe newest financial report from the UNC athletic department to the NCAA shows the department operated at a deficit of more than $15 million during the 2024-25 fiscal year. The department reported revenues of $172,951,034 and reported expenses of $187,967,260. The UNC athletic department had operated at a profit in each of the past three […]

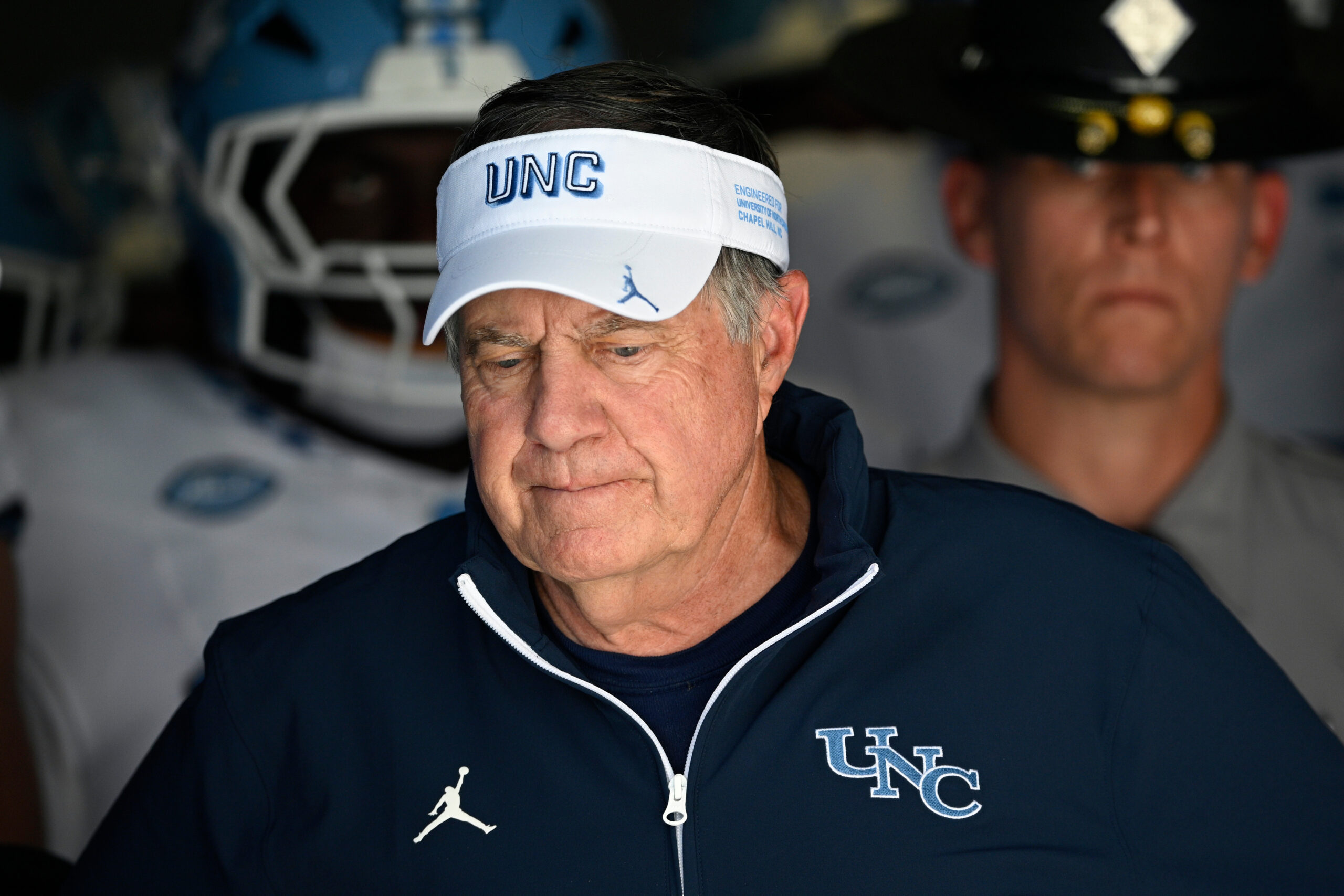

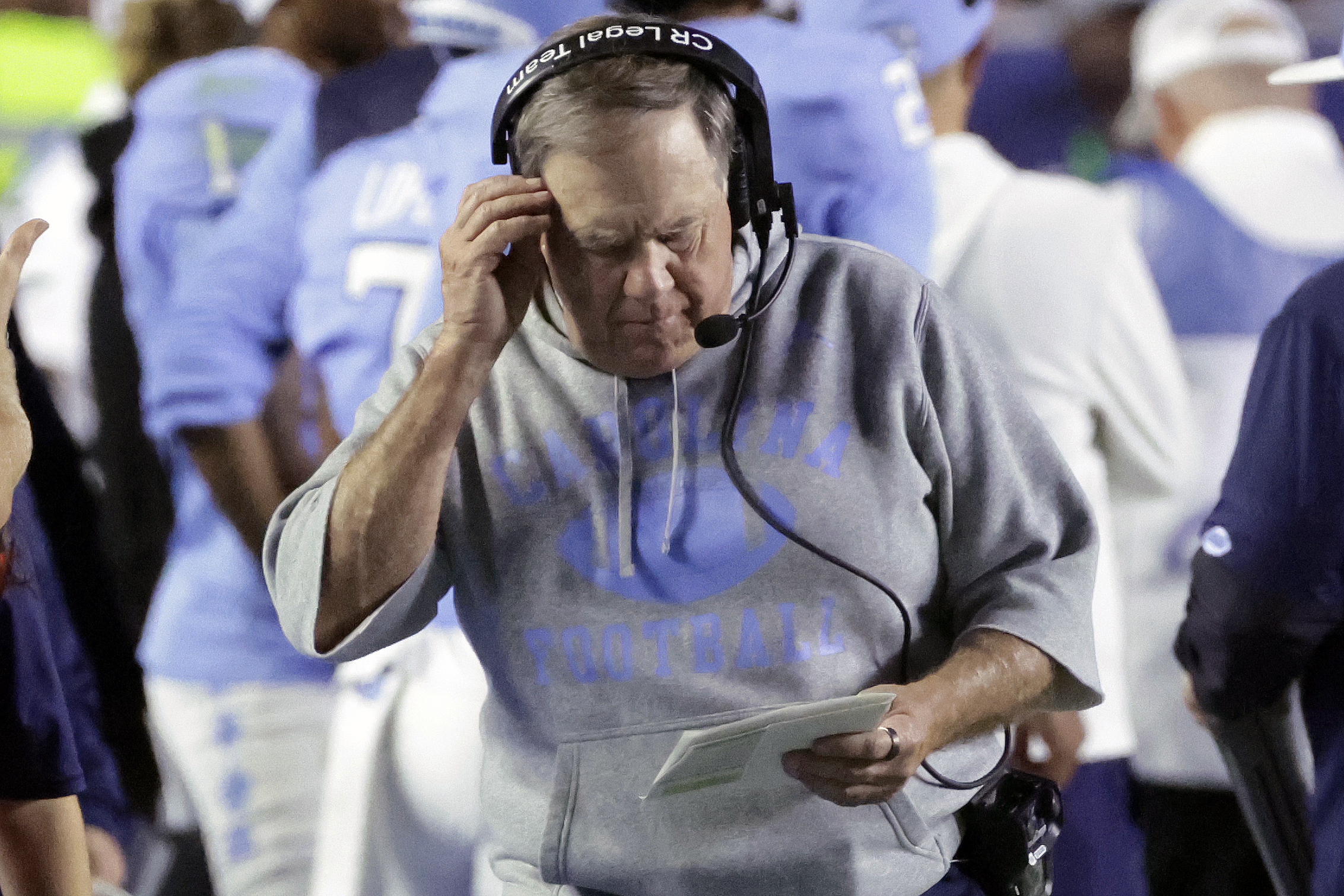

'Hard to Imagine': Newmark, Lombardi, Others Share Disbelief at Bill Belichick Hall of Fame VoteUNC football general manager Michael Lombardi and athletic-director-in-waiting Steve Newmark were among many sports figures to share their disappointment and surprise at reports that head coach Bill Belichick was not voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on his first ballot. An ESPN report published Tuesday night indicated Belichick, currently between his first and […]

Chansky's Notebook: Sophomore SlippageUNC's schedule for the 2026 football season is out, and Art Chansky says it is very, very bad news for Bill Belichick's second year.

Schedule Set for UNC Football's 2026 SeasonThe UNC football program now has its complete schedule for the 2026 season. The ACC revealed all of the league members’ schedules Monday night. Your 2026 North Carolina Football Schedule. 🐏 🔗: https://t.co/VQdkI47r8n🎟️: https://t.co/XERIbvZEH8 pic.twitter.com/6Zb5uSn1y3 — Carolina Football (@UNCFootball) January 26, 2026 UNC will open the season in Dublin, Ireland against TCU as part of […]

Here's a List of Which Transfers Have Committed to UNC Football in 2026The college football transfer portal opened Friday, Jan. 2 and closed Friday, Jan. 16. Here’s a list of players who have committed to head coach Bill Belichick and UNC out of the portal so far, with their classes for the 2026 season: QB Billy Edwards, Jr. (Most recent school: Wisconsin, redshirt senior) Ranked 3rd in […]

Several UNC Football Stars Will Return to Chapel Hill in 2026. Here's the Full List.In an era of unrestricted player movement in college football, teams are undergoing radical changes every offseason. Take UNC before the 2025 season, when the Tar Heels upended their roster and brought in 70 new players. This offseason, there is only one transfer portal window, between Jan. 2 and Jan. 16. More than two dozen […]

College Football's Transfer Portal Closed Jan. 16. Which Tar Heels Entered?The college football transfer portal opened Friday, Jan. 2 and closed Friday, Jan. 16. It was be the only transfer portal window of the year for college football, as the NCAA moved to eliminate the spring transfer window earlier this year. Players do not have to have committed to and signed with a new school […]

Chansky's Notebook: Building DepthThese days, college football recruiting is more about the money the athletes can now make in what has become a semi-pro system.

Chansky's Notebook: A Star is BornIn his second NFL season, Drake Maye has already established himself as the best quarterback that UNC football has ever produced.

›