I was a “honeymoon baby.” That is, I was a souvenir of my parent’s honeymoon. I was born exactly nine months to the day from when it started. My arrival was a mixed blessing at best. My father, a full time student working on his Master’s degree and a Ph.D. in Physics, and my mother, also a college student, needed an addition to the family like they needed a hole in the head.

To say that I grew up in a family of modest means is an understatement. But we never went hungry. One of my earliest memories is that of a large metal can on the kitchen counter stenciled with the words, “peanut butter,” in bold, government-style letters. Sitting next to it was a plain box marked “cheese” in the same stark lettering. I would learn later that it was something called “government surplus,” a precursor to food stamps. It was free, but you had to be poor to qualify for it.

Things got a little better as I grew older, but not much. There was little money in the house. What there was went to pay for necessities like nourishment and shelter. Those were needs. As I remember it, there was never a problem in our home making a distinction between needs and wants. Needs, I came to conclude, are absolute and gnawingly apparent. Wants are arbitrary and usually frivolous.

It troubles me that today’s society, especially in wealthy countries like the United States, is defined by its craving for instancy. Baby Boomers started the push button era sometime in the 1950s and soon, consumers were hooked on instant coffee, instant tea, frozen TV dinners and so many labor-saving devices that kitchens couldn’t contain them all. Now, we are addicts, and we have passed the habit on to our kids. The line of distinction between wants and needs always seems to blur when there is plenty, but usually comes back into sharp focus during hard times.

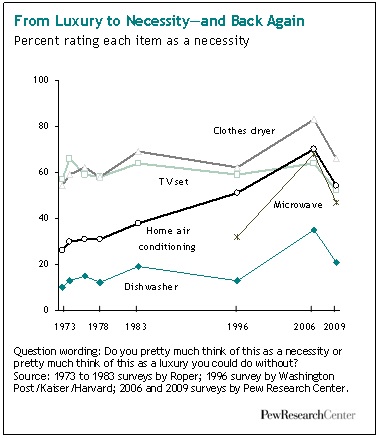

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Social and Demographic Trends project, Americans are rethinking what they can and cannot live without. It used to be that most folks saw such things as microwave ovens, home air conditioning and TVs as luxuries; now, more people see them as necessities. Do you have a cell phone? Could you part with it? Half of those polled said they viewed cell phones and personal computers as necessities. Food is a necessity. You can’t eat a computer. Would you go hungry to keep your cell phone? That is the true test, I suppose.

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Social and Demographic Trends project, Americans are rethinking what they can and cannot live without. It used to be that most folks saw such things as microwave ovens, home air conditioning and TVs as luxuries; now, more people see them as necessities. Do you have a cell phone? Could you part with it? Half of those polled said they viewed cell phones and personal computers as necessities. Food is a necessity. You can’t eat a computer. Would you go hungry to keep your cell phone? That is the true test, I suppose.

Economic recession has a way of teaching us priorities. Since the era of abundance in the 1990s, the television, the most sacrosanct of all luxury items, is now considered a necessity for only 52 percent of those surveyed — down from 64 percent.

The media bombards us daily with things that are attractive and appealing. Advertising moguls are paid millions to find new ways of making us want the things they dangle before us. Credit cards make them easy to purchase. It’s no wonder that some think there is a giant conspiracy out there, the purpose of which is to prevent anyone from saving anything! I know my mother would see it that way. “It’s a game,” she used to say. “And it goes like this: You have money in your pocket, and everyone around you is trying to get it out.”

Those words still come back to me every time I leave a Best Buy store with some new gadget that I felt sure I could not live another day without. I get that little tingle of conscience they call “buyer’s remorse.”

Our goal as retirement planners is to help people achieve a retirement where both their wants and needs are easily attained. But it’s still refreshing when people are able to recognize the difference between the two.

Coach Pete and his team offer complimentary retirement strategy sessions to Chapelboro readers. Contact them at 919-657-4201.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines