It was like the pleasure of a long letter from home.

At least it was for this exile from Charlotte and Mecklenburg County.

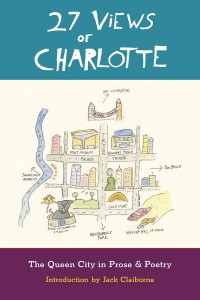

I picked up the new book, 27 Views of Charlotte: The Queen City in Prose & Poetry, to see if any of my friends were among the almost 30 contributors.

I picked up the new book, 27 Views of Charlotte: The Queen City in Prose & Poetry, to see if any of my friends were among the almost 30 contributors.

But when I started reading, I could not stop until I had read every selection, beginning with Jack Clairborne’s cheerful summary of Charlotte’s efforts to become a “world class city,” concluding that the key to its success has been its openness. “You don’t have to come from a particular family or industry or religion or race to make a place for yourself. If you have ideas and the energy to put them across, you too can be a leader. That’s part of what makes Charlotte a pushy and successful place.”

But if you are not from Charlotte, why should you be interested in how its writers describe the city and attempt to explain it to the reader? The answer is pretty simple. All of North Carolina is connected to that city. Think government: McCrory and Tillis. Or power: Duke Energy. Money: Bank of America.

So even you might want to know more about why Charlotte is what it is, especially if you can learn from a group of talented writers. For instance, UNC-Charlotte professor David Goldfield starts with Charlotte’s distinction as the last capital of the Confederacy because of its hosting President Jefferson Davis’s last cabinet meeting. Comparing Charlotte’s history with that of Richmond, another Confederate capital, Goldfield says that Charlotte’s “journey from Confederate capital to banking capital” is not like Richmond’s, “but it is a tale of industry (textiles), migration (black, white, and brown), entrepreneurial innovation, expansion of education, infrastructure improvement, Uptown revitalization, and lots of eager, bright young people attracted not only by the work, but also by the ethic.”

Goldfield concludes, “For Charlotte, the Civil War was just the beginning. The Confederacy ended here, and the New South began.”

Two deans of Charlotte’s writing community, Dannye Romine Powell and Mary Kratt, charmingly connect city monuments like the high-end Fourth Ward uptown residential area and the Duke Mansion to the people who lived there at the beginning and what they contributed. For instance, James B. Duke’s hydro-electricity powered most of the 300 mills within 100 miles of Charlotte, representing one-half of all the mills in the South.

Other powerful writers show the connections between the city’s treasured Latta Arcade and the farm families who once brought cotton to market there; the link between food and the struggle for racial justice; the relationship with returning soldiers; the rise and fall of a once-elegant shopping center; the experiences of residents in the all-black Second Ward, now all gone, and others like College Downs near UNC-Charlotte.

As I kept reading, I found a poignant story of the people living on one of the last nearby farms and the farmers’ remarkable relationship with the traveling circus that stabled its horses on the farm; a portrait of Charlotte’s favorite cowboy, Fred Kirby, who helped make a Charlotte station the television capital of Western North Carolina; a description of the funeral of the author’s sister; complicated and scary crime stories; descriptions of streets that change names without warning; how the city took the shock of the loss of Wachovia, the wild-west-like story of the construction of the Charlotte Motor Speedway; and a loving description of Charlotte’s love affair with trees that asserts “trees are the life of Charlotte’s party.”

Great writing and wonderful stories took me all the way to the final one by former TV anchor Bob Inman, who concluded with a celebration of “the tradition of good people seeing that a good place can always be made better, and acting on it.”