I remember my first (and only) interview with Dr. Linnea Smith the year after she married the famous basketball coach at UNC. A psychiatrist, she was confidential by nature and knew her husband preferred privacy over the very public figure he had become teaching and coaching a game that was growing faster than he ever imagined.

Dr. Smith understood the trappings of Coach Smith’s career, but she was bemused by a perceived influence that far exceeded his profession. She used the word “omnipotent” to describe how many people regarded her husband. It was one of the last interviews Dr. Smith ever granted, acceding to that fierce discretion Coach Smith demanded within his family, program and personal life.

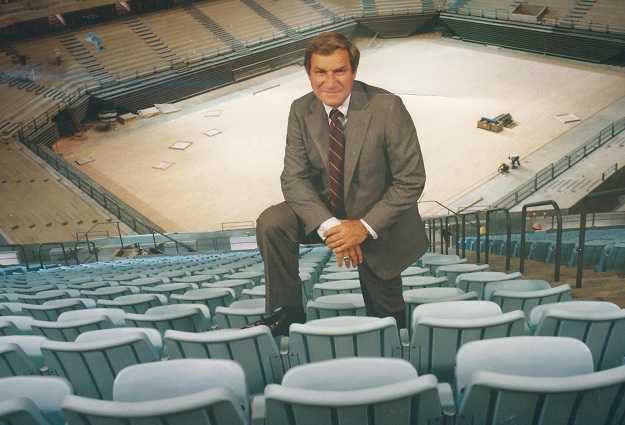

Photo courtesy of The Herald Sun

You will read dozens of tributes to Dean Smith over the next few days, some lionizing the late Carolina coach for teaching them how to conduct their lives. He wouldn’t want you to believe everything you read. We all know how he disdained taking credit.

Yes, he knew how he wanted to conduct his own life and he tried as he might to live by those standards he learned from his parents, mentors, coaches, pastors, philosophers and authors he admired. But above all, Dean Smith knew he was human and with that came the foibles, the temptations, the emotions that we all have.

And in the ultra-competitive arena in which he lived his life, he did mess up every now and then, sometimes say the wrong thing or let the loyalty he felt for his players and associates get the best of him.

When that happened, he hoped he would not make the same mistake twice, whether it was a snap judgment about someone or calling the wrong offense against a certain defense. But more often than not, when Coach Smith did raise an eyebrow, he knew exactly what he was doing and never apologized for what he believed was the right course of action.

He did not see his life as a blueprint for how others should live theirs. Except within his basketball program, which he described as a benevolent dictatorship, he merely did what he thought was right while always recognizing that not everyone agreed it WAS right.

A teacher at heart, he struggled with the concept of playing poorly and still winning games. He wanted his teams to play well and let the results fall where they may. He was better at that than most coaches, often comforting assistants, friends and fans about an extremely tough loss. But he took them hard, too, and regretted what he thought he could have done better.

He was harder on his players after poor performances because he saw those as teaching moments for impressionable youngsters. He held them accountable, hoping they would form good habits in the process. Only after they were finished playing for him did they become his friends. And they were friends for life; he always knew where they were and expected them to stay in touch.

He had bad habits, like chain smoking and eating too much. On those faults, he advised others against doing what he did. He apologized to recruits on whom he was trying to make a good impression when they saw him smoking. “It’s a bad habit,” he would say, “I am trying to quit.”

He did eventually, and from then on it was non-stop Nicorette, subtly moving around in the side of his mouth.

He was raised to be a good sport, and he was most of the time, congratulating and praising the opponents to the point where you wondered if he were covering for his own team’s failings.

He bit his tongue almost always, thinking how something might sound before he said it. He had a favorite expression: “Don’t get mad, get even.”

If his team lost a game it should have won, he knew there would be another chance. If an official made an irresponsible call, he would stay on that ref until the zebra got one right. A make-up call, some people called it.

Dean Smith was loyal to a fault. “His greatest strength and his greatest weakness,” his closest associates said about him. He would not push or recommend someone outside the Carolina Basketball Family for a job until he was sure no one inside, even a less qualified candidate, wanted it.

He believed in promoting from within and, admittedly, sometimes that was self-serving because he grew stubborn as he grew older and did not want to change just for the sake of change. And when he believed strongly that his way was the right way, he occasionally wielded the great power he had gained to make it happen.

He wanted his players to get a college education and graduate, and some of the athletes he recruited were more capable on the basketball court than in the classroom. So he made sure those players found courses they could handle as well as learn something. He had three rules: go to class, do the work assigned and get help from tutors but not too much help.

That’s why his graduation rate was so high, because most of his players abided by those three rules. Coach Smith knew what courses they took, his assistant Bill Guthridge walked around campus to check on class attendance, and the teachers and tutors told him if any of those players weren’t doing the work the right way.

He said it was okay to tattle so he could cut off trouble at the pass.

Only on occasion did it get so bad that he had to suspend a player. But, as long as it was still up to him, he did not banish anyone from the Carolina program, trying to reform even the worst apples because, after all, he had invited them in. He reasoned that families should discipline their children to the extent of the bad behavior, but never throw them out in the street.

He believed in racial equality, fought for the nuclear freeze and against the death penalty. But most of the time he respected dissenting opinions. When a former player, Richard Vinroot, ran for Governor as a Republican, Coach Smith the liberal Democrat supported Vinroot as a smart, honest and patriotic person if not necessarily his candidate of choice.

He protected his players and insulated his program to the point of being a control freak. The autonomy he built became the model for many other things at UNC, athletic and not. His was a closed fiefdom with an open-door policy and remained that way after, sadly, he no longer knew who it was crossing his threshold.

And, at the end of his career, when it was time to walk away, he did so with the same measure of privacy as he lived his life. He rarely came back into the arena that bore his name, choosing to stay home and watch the games that his success had turned into regular TV shows.

Imagine how loud the cheer will be now at the end of the promotional video at home games when Dean Smith says, “THIS is Carolina Basketball.”

He was proud of the program he built for all of its human qualities, most good and only a few not-so-good. He WOULD tell you that.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines