While you are watching U.S. Senate campaign television ads, occasionally interrupted by brief segments of programming, do you ever wonder what goes on inside the candidates’ campaign organizations?

For instance, what if you could take on the role as the top aide to an incumbent North Carolina U.S. senator running for reelection against a top state official who has a full war chest of campaign funds? Interesting? Challenging?

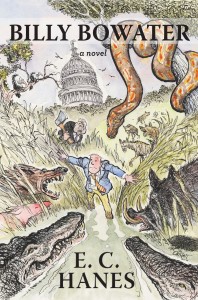

A new novel, Billy Bowater, by Winston-Salem civic leader E. C. “Redge” Hanes is a fictional version of such a campaign. William Walpole Bowater III, the book’s central character, is chief legislative assistant to incumbent Sen. Wiley Grace Hoots. Like the author, Billy Bowater comes from a prominent North Carolina family, one in which expectations for performance and service are demanding.

A new novel, Billy Bowater, by Winston-Salem civic leader E. C. “Redge” Hanes is a fictional version of such a campaign. William Walpole Bowater III, the book’s central character, is chief legislative assistant to incumbent Sen. Wiley Grace Hoots. Like the author, Billy Bowater comes from a prominent North Carolina family, one in which expectations for performance and service are demanding.

Family connections got Billy a job on Sen. Hoots’ staff, but his hard work and willingness to do what it takes earned him the top staff job and a leading place in Hoots’ reelection campaign effort.

Meanwhile, back at the real current senate campaign, polls indicate a tight race between incumbent U.S. Sen. Kay Hagan and the challenger, state House Speaker Thom Tillis. But even with an overflow of television ads, this contest has not yet gathered the same level of public interest, commitment, and passion as some of the North Carolina classic Senate races, like the Frank Graham-Willis Smith race in 1950 or the Jesse Helms-Jim Hunt race in 1984.

The Hunt-Helms race is obviously the model for the election campaign chronicled in “Billy Bowater.” Billy’s boss, a conservative incumbent senator who is much loved and much hated for his conservative viewpoints, is Wiley Grace Hoots rather than Jesse Helms.

The popular governor with campaign coffers full of cash is Randolph James rather than Jim Hunt.

The publisher of the Raleigh News and Observer is Daniel Frank, rather than Frank Daniels, Jr.

Billy loves his job and the power that comes with it, but he has to wrestle with his conscience when he finds himself on opposite sides of important issues from his boss. He justifies continuing to work for Sen. Hoots because, as he says, Hoots, not Billy, was elected senator. Billy was not elected anything. So it is Billy’s job to help Hoots accomplish his agenda.

Billy admires Hoots for his strong conservative principles. Unlike many other politicians, Hoots operates on the basis of those principles even when political winds are blowing in a different direction.

Nevertheless, Hoots can play hardball when that is what it takes to win.

Redge Hanes

“Billy Bowater” takes readers inside the campaign’s top leadership meetings, where the main challenge is to raise enough money to fund the campaign. They focus on finding an issue that will make potential donors angry, angry enough to send lots of money to the campaign.

Billy watches as that issue presents itself in the form of an exhibit at the Ackland Art Museum at UNC-Chapel Hill. One of the exhibits features a man urinating, seemingly on a figure meant to represent Jesus, just the kind of art that would make people angry and generous to a candidate who stood against such sacrilege.

The challenge to the Hoots campaign is how to use the exhibit to inflame supporters and donors but to do it without direct criticism of the university and its alumni, many of whom are judged to be likely Hoots supporters

To get the issue before the public, the crafty senator enlists his friend, the Rev. Earl Caldwell Anthony, head of the Christian Crusade, to raise the issue with the millions of his followers.

Hanes makes a good story as his characters wrestle with these challenges. What I enjoyed the most was the opportunity to hear discussions among aides, campaign managers, media consultants, and fundraising committees and see how hard it is for each candidate to keep the people on the campaign team from eating each other alive.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines