There are many kinds of heroes. There are the ones who make the news, who emerge in a crisis and do something extraordinary; there are the ones who stand up and cry out against injustice, even at the risk of their livelihoods and lives…and then there are the quiet heroes, the ones who go about their business, the ones you never really see. They face their adversities, sometimes with courage, sometimes with resignation, sometimes with anguish and bitterness and rage – but they face them, always, and the world turns on, just a little easier, just a little better.

I’m thinking about heroes this week. On Sunday WCHL hosted our big annual luncheon for all the folks we’ve recognized as Hometown Heroes throughout the year; outgoing fire chief Dan Jones delivered a terrific speech about the heroism he sees every day and the value of “paying it forward.” We recognize all kinds of heroes – sometimes the special ones who come through in a crisis, but more often than not the everyday heroes, the quiet heroes, the firefighters and police officers and community builders and teachers and volunteers.

Down in Alabama, it’s not so quiet. It’s the 50th anniversary of the Selma marches, and there are thousands of people there now – including many from our own community – remembering the stand those marchers took in 1965, the risks they assumed, the sacrifices they made, the lives they gave, calling for justice even as the blows rained down around them. Heroism.

So it’s fitting that both of our local theater companies, PlayMakers at UNC and Deep Dish at University Mall, are running plays about heroism this month: the World War I classic “Journey’s End” at Deep Dish and the Henrik Ibsen/Arthur Miller collab “An Enemy of the People” at PlayMakers. Both shows are essential: challenging, troubling, disturbing, and difficult, but essential nonetheless. Check them out.

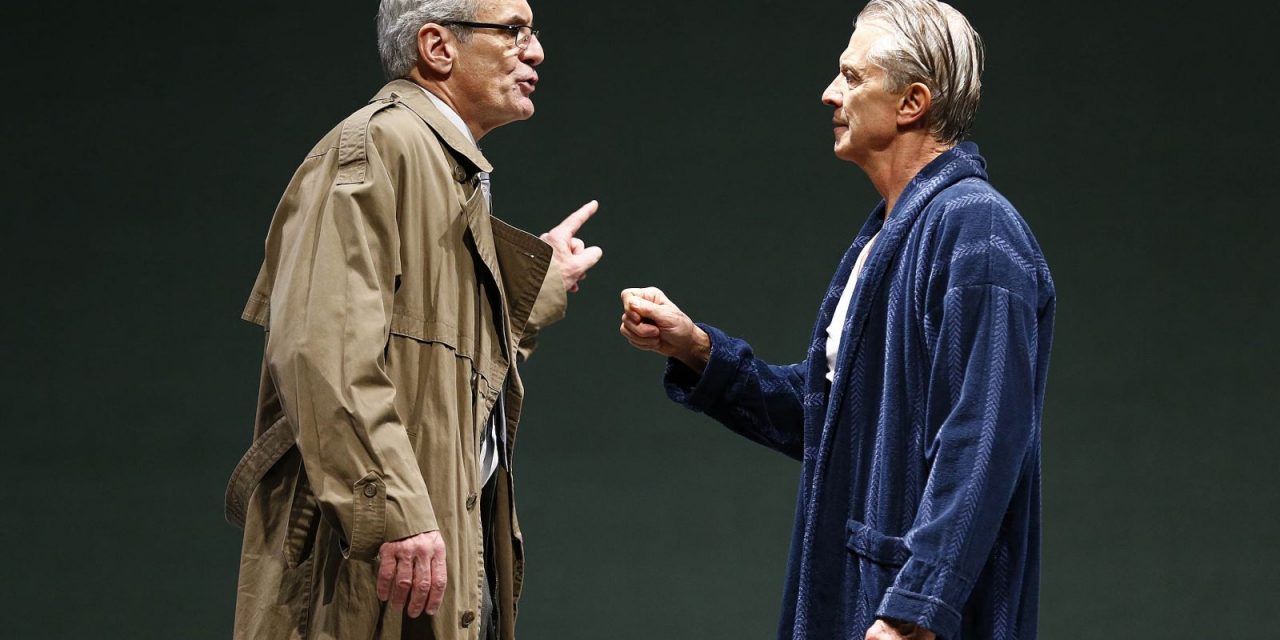

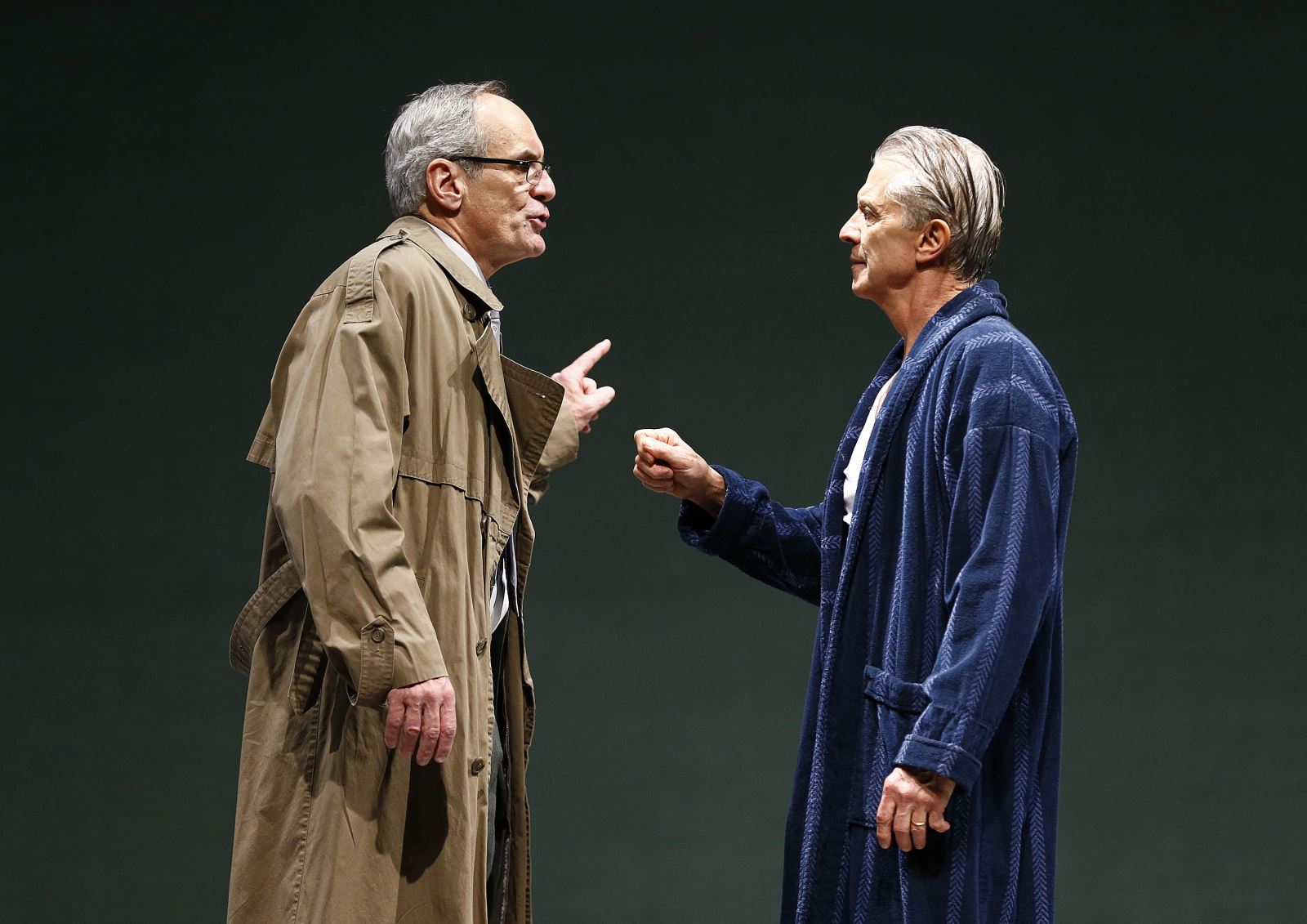

“Enemy of the People” is about a loud hero, albeit one who maybe didn’t intend to be. Thomas Stockmann (Broadway vet Michael Bryan French) is the official physician of a small town whose economy hinges on a single tourist attraction – a public health spa with water from a local spring. But the water is contaminated, Stockmann discovers, with germs from a tannery upstream. The town must know! But the mayor (fellow Broadway vet Anthony Newfield) cares more about the economy – the local muckraking newspaperman (Benjamin Curns) is a sellout – the business leader (Jeffrey Blair Cornell) refuses to upset the established order – and the nameless rabble of townsfolk are easily convinced that Stockmann’s just a malicious agitator. He’ll stand alone – the sole voice for justice and truth in a vicious and misguided world. Henrik Ibsen wrote the play as a critique of mob rule in a democracy; Arthur Miller adapted it into English as an allegory of those heroes who stood up to Joe McCarthy in the 1940s and 50s. (And its cultural reach extends even further: the struggle between the corrupt mayor and the sole-voice-of-reason scientist reminded me of “Jaws,” and indeed “Jaws” was reportedly inspired by this play.)

Anthony Newfield as Peter Stockmann and Michael Bryan French as Thomas Stockmann in “Enemy of the People.” (Photo by Jon Gardiner via PlayMakersRep.org.)

Meanwhile across town, “Journey’s End” takes us to the trenches of World War I, where six British officers are barracked just before a major German assault. Osborne (Eric Carl) is the “uncle” of the group, who keeps the rest sane – especially Stanhope (Gus Allen), a brilliant officer who’s having trouble keeping it together. Osborne and Stanhope are quiet heroes, caring for others before themselves, doing their best to soldier through, put on brave faces, and not let on that they too are afraid, anxious, bitter. In contrast to Stockmann of “Enemy,” who stands alone, Osborne and Stanhope and their fellow officers stand together – knowing that if one falters, the rest will fall. (Like “Enemy,” “Journey’s End” is historically significant: along with “All Quiet on the Western Front,” it’s one of the first pieces of literature to depict war realistically, without all the glorious/patriotic overtones you so often see. Playwright R.C. Sherriff was himself a WWI vet; he said he simply wanted to show the war as it was.)

You’ll want to see both before their runs are up. At Deep Dish, scenic designer Michael Allen has created a stunning recreation of a WWI barracks; you can smell the wood as you enter the theater. Carl’s stellar performance as the kindly Osborne holds the show together, bolstered by terrific supporting turns from Carl Martin as the unflappable Trotter and David Hudson (also great in DD’s “Life Is A Dream”) as Mason the cook. At PlayMakers, director Tom Quaintance makes full use of the versatile stage (the dark ending is particularly spectacular) and French and Newfield anchor the show as the main antagonists. (Did I mention their characters are also brothers?)

But it’s the celebration of heroism that stands out. It’s easier to cheer for Stockmann, the loud hero of “Enemy” who stands up to injustice – on opening night, the woman sitting next to me kept nodding her head and saying “Yes!” when the character was delivering his choicest lines. He’s a whistleblower, a crusader for truth, and we all like unfairly maligned whistleblowers and crusaders for truth. Then again, Stockmann is also a deeply flawed character in a way that “Journey’s” heroes are not: he’s prideful, stubborn, a blowhard, a hard-head, willing to throw his family into the line of fire even when offered an easy way to withdraw quietly and let the truth come out on its own. We sympathize with him, we might pity him, but we probably don’t like him. The heroes of “Journey” are more pristine: Osborne is fiercely other-regarding and quietly self-sacrificing; Stanhope is less sympathetic – given to drinking and angry outbursts – but we know it’s only the strain of war that’s made him that way. They’re not the sort of rah-rah heroes you stand up and shout for, like Stockmann is – but their quiet bravery is every bit as heroic as Stockmann’s brash stand. Maybe more so.

In the end, though, it’s not the fictional heroes on stage that matter so much as the real ones in the audience. “Journey” and “Enemy” both hold up a mirror to us as spectators and force us to examine ourselves: how heroic are we? In “Journey’s End” we see all kinds of soldiers, from the gung-ho and brave to the cowardly. (“Coward” here is a relative term: all the soldiers are terrified of war; it’s merely a question of how they handle it.) Where on the spectrum would we fall? In “Enemy” the mirror rises in an even more dramatic way: partway through the second act, the actors very purposefully look the audience in the eyes and give them the chance to speak out against the injustices they’re seeing on stage. (You’ll know what I’m talking about. It’s a palpable moment.) In that moment, the fate of the characters is in our hands: we could stand up, we could raise our fists, we could shout. It would alter the rest of the show, of course, but we could do it! But of course we don’t. We’re angered by the injustice, but we don’t speak. We’re just the audience. We’re there to observe. It’s not our place. It would upset the order of things. And we’d never upset the order of things. It’s a nice, respectable theater, after all. This isn’t Rocky Horror…

And so the moment passes, and the injustice proceeds.

And when the lights go up we stand and give a rousing, rah-rah ovation to the cast.

“Journey’s End” runs at Deep Dish from now through March 21; visit DeepDishTheater.org for showtimes and ticket info. “Enemy of the People” runs at PlayMakers through March 15; visit PlayMakersRep.org for showtimes and ticket info.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines