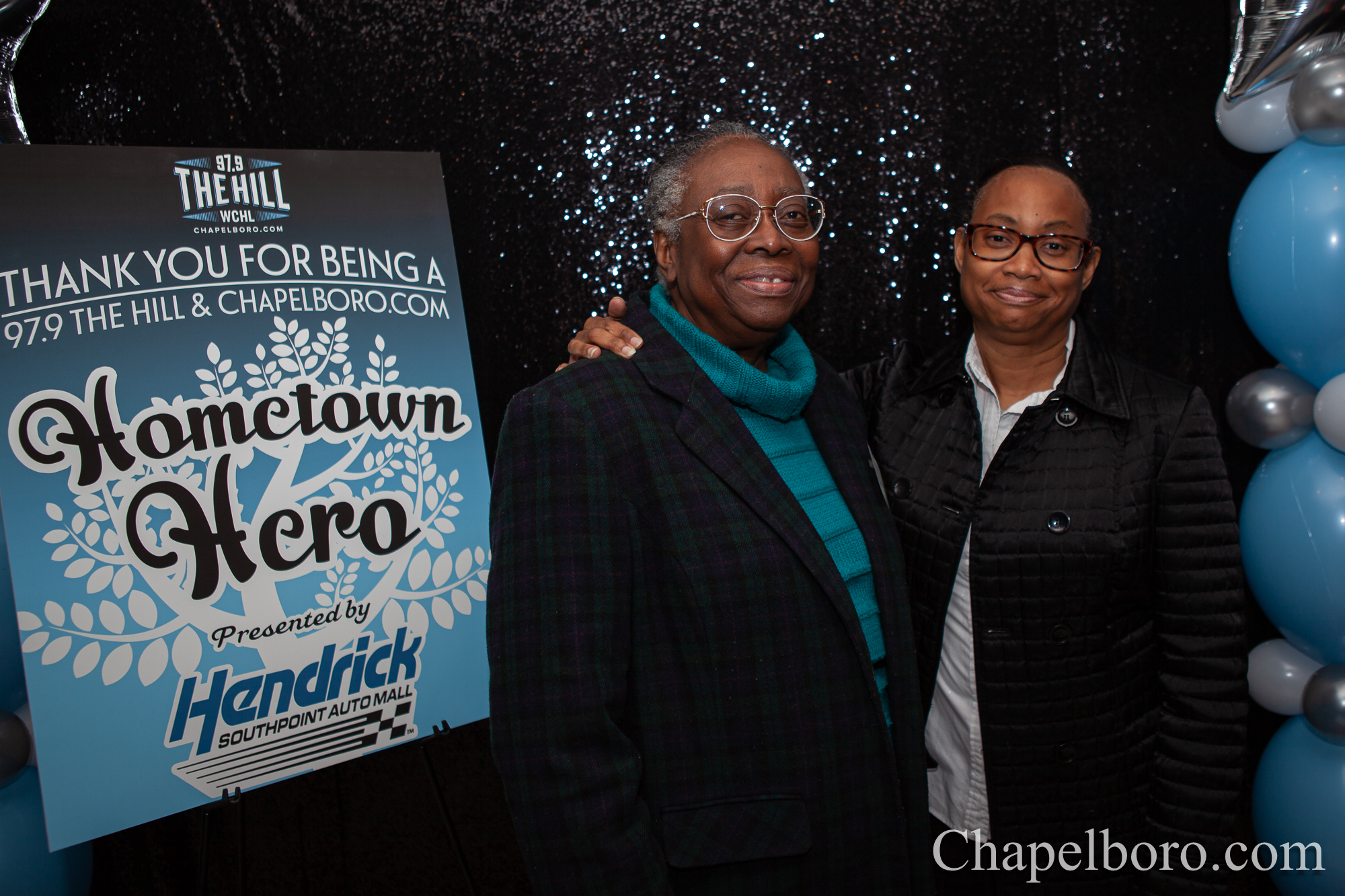

On February 23 at the Carolina Inn, WCHL hosted our annual luncheon to recognize this year’s “Hometown Heroes,” winners of our daily Village Pride Award. This year’s keynote address was delivered by Freddie Kiger – and his speech was so moving that we had numerous requests to reprint it.

What follows below is the text of Freddie Kiger’s speech, delivered February 23, 2014 in Chapel Hill, NC.

—————————-

As speaker protocol goes, one opens with an amusing anecdote. So here’s my stab at it:

This car went by the patrolman at 22 mph. He thought that could be as dangerous as speeding so he stopped them. When he reached the car, he found five elderly ladies—all, except the driver, looking pretty pale and in a state of shock.

“Oh officer, I don’t understand,” said the driver. “I was going exactly the speed limit.”

“Ma’am, you weren’t speeding, but you were traveling so slow that I felt you were a danger as well.”

The little lady replied, “Slow? I was going exactly what the speed limit sign said: 22.”

Immediately, the trooper figured it out and smiled. “Ma’am, that wasn’t the speed limit. That was the route number.”

The driver blushed, grinned and thanked the officer for pointing out her mistake. The trooper backed away, but then stopped and said, “Before I go, everyone else looks quite shaken. Is everyone in the car OK?”

“Oh, they’ll be fine in a few minutes. We just got off Route 119.”

——-

You know, I’m glad Ron’s here. For over 10 years, we’ve had a great time spreading trivia, and today, if my memory serves me correctly, this may be the first time we’ve taken minutiae on the road. Today we’re talking gyros, and I found something I can’t wait to share with you guys.

I don’t know about you but I love gyros. Maybe you remember the ones down at Hector’s. Well, you might ask, how did pita-bread sandwiches come about? According to Davanco Foods in Elk Grove Village, Illinois, “Papa George” Apostolou is the father of today’s gyros: as the story goes, he served up the first one at Chicago’s Parkview Restaurant in 1965…

What?

Oh, hero, not gyro.

Ah! I got it! From Greek mythology—great story. You see, Hero was this priest of Aphrodite who lived on the European side of the Dardanelles, and this dude named Leander who lived on other side of the strait fell in love with her. Every night, guided by a light she put out for him, Leander would dive into the water and swim across the Hellespont to be with her. One night, however, the sea was stormy and her guiding light went out. Leander, who was already in the water, strayed, drowned and, when Hero learned of it, she threw herself into the sea—kind of the Greek version of Romeo and Juliet…

What?

Oh, heroes! Got it. Please forgive my horsing around with you…

——-

Of course, I know why I’m here—and, more importantly, why all of you are here. You’re part of the material that makes our community dynamic, part of the fabric that makes our little corner of the world unique.

And, over the years, we’ve been lucky. We’ve had many who, patch by patch, have contributed to this multi-colored quilt that warms and comforts all of us that call this place home.

Like Otelia Cunningham Connor, who campaigned heroically for her crusade: good manners.

In 1957, she came over from Durham for her son’s graduation…and all the pushing, shoving, slouching and slurping pushed her right over the edge. Her mission now defined, she moved to Chapel Hill and made the rounds in Lenoir Hall, where students dined. If you had your feet on a table, borrowed a chair without asking, didn’t open a door for a lady, said “huh” or “uh-huh,” slurped—or, God-forbid, burped—mild-mannered Otelia went into her imaginary phone booth and emerged as Super Nanny, armed with an umbrella for thwacking heads, hands and shins in the most un-mild-mannered-like fashion.

Her back-up weapon was a cocked finger—ready to snap any skull that might encase a brain that even thought about rude behavior.

The Dean of Students called her an anthropological treasure, “a throwback to those lost days when manners counted for something.” Unappreciative, thwacked and whacked students called her “a hell-raiser,” “an apparition,” “a little toothpick of a woman with a cigarette dangling out of her mouth.” Those barbs didn’t stop her. Once, she made a good manners reconnaissance raid over to Duke—and, like a good Tar Heel, reported their manners even worse than ours.

Our heroic Maven of Good Manners—Otelia Cunningham Connor was certainly larger than life.

Another Village hero was just as big…only smaller.

Billy Arthur was Chapel Hill’s self-proclaimed “One Yard of Fun.” It’s hard to imagine all the stories and life that came out of this 40-inch-tall, 60-pound story-teller, entrepreneur, ham, clown, gourmet, former vaudeville star, UNC head cheerleader, journalist, state legislator and bon vivant.

In 1953, he became a columnist for the Chapel Hill Weekly. There, he continually wrote a daily or weekly column for decades. Well, they say “the pen is mightier than the sword”—and it sure was, in the hand of this little man who, heroically, saw the forest and the trees.

Here are some of his gems:

In July of 1972, he wrote this about the Democratic National Convention: “There was a lot of talk about committed delegates, and I got the feeling several times that some of them had been paroled.”

During the height of the UNC Speaker Ban which was passed by the NC Legislature back in the early 60s, he wrote, “I wonder what the Legislature will do when they find out Tarzan didn’t marry Jane, and Snow White lived with Seven Dwarfs.”

On Governor Terry Sanford’s food tax, he wrote, “Sanford said the food tax was the best way to have quality education. But that’s like putting garlic in the baby’s milk. Not only makes him healthy but easy to find in the dark.”

Sage-like, he wrote, “Some people want to die rich. I want to die old.” He did—in 2006 at the age of 95 after years of crusading, armed with only a pen and quick wit.

We should take pride in another Chapel Hillian who battled for social and civil justice.

Jesse Robert Stroud was, once, the bellman right here at the Carolina Inn. He was, also, a civil rights activist. As a frequent letter-writer-to-the-editor, he, like Arthur, made his pen a weapon for righting wrongs. He made some feel uncomfortable—and in the segregated days of the early 60s, they needed to.

Here’s one entry—a paragraph that still speaks volumes:

“I used to think I was ‘poor.’ Then they told me I wasn’t ‘poor,’ but that I was ‘needy.’ Then they said it was self-defeating to think of myself as ‘needy,’ that instead I was ‘culturally deprived.’ Then they told me that ‘deprived’ had a bad image, that I was ‘underprivileged.’ Then they said that ‘underprivileged’ was overused, that instead I was ‘disadvantaged.’ [Well,] I still don’t have a dime, but you must admit: I have an atomic vocabulary.”

Jesse Robert Stroud, indeed, had a nuclear vocabulary—one that preached fusion, that demanded equality and equal access for all races.

Now, if Stroud had a sharp eye for social injustice, here’s a campus hero who had an eagle eye for detail—and for cutting through red tape to get things done.

William Donald Carmichael was a 1921 graduate of UNC, a campus basketball star and brother to hoops All-American Cartwright Carmichael. He was also comptroller, VP and one-time acting president of the UNC system—in short, a mover and shaker.

Here’s an example.

Head Coach Frank McGuire wanted a basketball gymnasium to rival Reynolds Coliseum over at State. That was going to take some doing. The first time McGuire walked into Woollen Gymnasium, he asked for the lights to be turned on.

He was told, “Coach, they are.”

There were many other problems—one of them, leaks. McGuire complained to Carmichael about them…and learned it would cost $20,000 to get ’em fixed. He was told the state legislature didn’t have that kind of money.

Well, our Billy had a solution. He went to work—and lo and behold, the Monday following a Saturday home game against NC State, word came in from Raleigh that $20,000 had just been allocated from the Emergency Contingency Fund.

What happened in the course of 2 days?

Well, it seems Carmichael got some tickets for that Saturday’s State-Carolina game in Woollen, gave them to members of the Appropriations Committee of the General Assembly—and that Saturday, it rained like crazy.

Yep, their seats were directly under the leaks.

Mr. Carmichael was quite the man.

So was another…and he holds great interest for yours truly.

——-

He was born to parents who were farmers in Stokes County. Little did he know that his destiny would be dictated by events far beyond his control. When so many of us wondered what university we would attend, he had a reserved seat in a terrifying classroom known as World War II.

From his diary dated May 20, 1944: a flash flood in northern Wales, more than likely, saved his life. On that rainy Saturday, his infantry unit lost all their equipment. Unable to be re-supplied in time, they missed their assigned role in the storming of Omaha Beach on June 6. Instead, his unit came ashore Omaha D-Plus 12.

They may have missed the fighting on the beaches—but the fight found them a few miles inland. Plugged into the front lines around St. Lo, this GI didn’t know it then—but of the 200 who landed with him, only 13 would make it back home.

Before he landed in France, his letters described scenes that came through the eyes of a farmer. He wrote of the weather, cattle and crops.

But that idyllic innocence soon ended. Descriptive prose about the land gave way to short choppy entries which detailed events that had to be horrifying to experience and gut-wrenching to write.

He went on line June 26, 1944. His entry that day was one sentence:

“First shell came near, everyone scared to death.”

The next day, another brief note:

“Slept in my first fox hole last night.”

Then came a string of entries that changed him forever. This young man—all of 21 years old—witnessed war as it is, has been and will always be.

From his diary:

June 29, 1944: “First buddy got killed in my company, Bucchini got killed by a sniper.”

June 30: “…Sandledecker got killed, second [buddy].”

July 1: “Another buddy De Legge got killed, nicknamed ‘Bones’…a good pal.”

July 4: “Pushed off at 5 am. I was on guard when artillery barrage went off. Scared to death, tanks came by.”

July 5: “Most of my buddies were killed and wounded yesterday.”

July 6: “Suicide fighting…terrible…Crisman, Cain, Jacobs, Baker and Shubert [all] killed.”

Ask any common soldier what war is…and regardless of battlefield or century, he’ll tell you it is tedious, mind-numbing boredom interrupted by flashes of sheer terror.

Those diary entries that began June 26 burned that lesson into this farm boy’s mind, body and soul.

Those images haunted him until the day he died.

Incredibly, he made it all the way to Germany—and along the way was decorated with a Purple Heart and Bronze Star. With the war won, he came home. There was two years of business school, and in 1949, he married Mary Evangeline Waggoner.

Three years later, I came along.

——-

When I think of my Dad, I remember positive energy—a man with a contagious smile and infectious personality.

He lit up rooms, this man who never met a stranger and never retreated from any call to help another.

If there was a need, he acted.

If he could serve, he was front and center.

From a long list: he helped to create the North Forsyth Little League. He was a Board of Elections official. He served on countless community committees. He was President of my elementary and junior high school PTAs. He was an elder in our church. In his haven—his garden—he planted, tended and harvested almost all the vegetables and fruits we ate throughout the year.

I do remember as a child that I didn’t understand why he was not at home many weekday evenings until late. Mom told me he was busy doing this or that. Once she told me he was off selling encyclopedias. I wondered why.

At 17, I went off to school. Four years later, just a couple of weeks before I was to fulfill my father’s dream—to get an undergraduate degree from Carolina—I got a phone call from home.

The tone was chilling.

“Get home quickly.”

I’ll never forget that call and I’ll never forget walking through the door of the hospital room at Forsyth Memorial. There, before me, my full-of-life father…helpless…cut down by a stroke and fighting for his life.

In time, he was stabilized. But the stroke paralyzed the right side of his body. His speech was also severely impaired. It meant that after 29½ years, he had to retire from Reynolds Tobacco Company.

He was only 52.

He did not deserve that fate.

There were months of rehabilitation and countless trips back to the hospital to address numerous complications. Yet, with the help of doctors, the around-the-clock efforts of my saintly mother and the most powerful medicine of all—that of love—he made great strides. Still, mind you, he lost the use of his right arm and leg…and talking with him was a series of fill-in-the-blanks.

He had every right to be bitter. But that was not the stuff that made up Fred Oliver Kiger.

He battled back to be as complete as possible.

Oh yes, he was vulnerable. There were repeated cases of phlebitis. Eventually it was so severe that doctors amputated his right leg just above the knee. And there was the day-to-day dilemma—the maddening frustration of just trying to communicate.

Yet, through it all, he never let it beat him. Still one of my favorite memories: Dad, squeezing my hand with his left and, with crooked smile, vowing to me that he was going to get “better or bust.”

The stroke knocked my Dad to the floor. But his burning passion for life allowed him to soar.

He did more than just survive—he lived. And, more than that, he thrived. With that one good leg, one good arm, and the indestructible will to squeeze the life out of each and every day, he lived the last 27 years of his life more completely than many who have their health but have no idea what is means to lust for living.

——-

Three years after his stroke, I prepared to move to Chapel Hill. I had been hired by Herb Allred to teach at what was then Phillips Junior High School. At our last meal together, before I was to permanently change my address from Route 2, Tobaccoville Road and Rural Hall to J-14 Village Apartments in Carrboro, I distinctly remember—in broken phrases—my Dad asking me my salary.

I didn’t want to tell him. Quite honestly, I was embarrassed to tell him. Even with a Master’s degree, it wasn’t much.

After a few awkward moments, I said, “$12,500.”

Across the table, I watched my Dad drop his head.

I felt sick. I felt I had let him down. Years of education, and yet I was going to be compensated so poorly. I blurted that I knew it wasn’t much, I added that I didn’t need much to get by—but, reading his expression, I wasn’t very convincing.

We finished supper under a cloud.

A little later, when I was about to leave my childhood home, my mother stopped me in the hall. There, just we two, she tried to explain my father’s reaction. I interrupted. Again, I apologized for disappointing him.

It was then, she interrupted me.

“You didn’t disappointment your father. You’re going to make more than he ever made any year of his life.”

I was floored. It was my first step in growing up…in becoming an adult.

Here was a man—my father—whose childhood was dominated by the Great Depression, a man who shared a tobacco-farming family’s meager existence with six brothers and two sisters. Here was a man who couldn’t go to college, but instead was thrown into a world war. And even that wasn’t enough. In 1950, he was called to active duty to go to Korea—but was excused when doctors found a bleeding ulcer caused by the previous war.

This was the man who worked almost 30 years at Reynolds Tobacco Company…and never made more than I did as a first-year teacher.

And, yet, he—the provider—provided.

Thanks to my Mother, I now know how much he worried to make it all work. But at the time, I had no idea. He made sure I got to be a kid. Made sure there were Christmas, birthday and surprise gifts. Made sure there were dance, piano and organ lessons. Made sure that if I was sick, I received the best of care. Though he struggled mightily to make ends meet—selling encyclopedias and taking on countless odd jobs—he made sure my sister and I never, never worried about shelter, food, clothes, security…and most importantly, about being loved.

What love! What sacrifice!

As I stand before you—in a room filled with giving and dedicated people—I cannot help but think of your sacrifice. I cannot help but think of my Mother and Father’s sacrifices.

They are my heroes.

——-

My Mom still lives on Tobaccoville Road. She’s still in the same house where I was raised. I lost my dear father August 5, 2001. I am so thankful that before he passed, I got to tell him how much I loved him—how much I appreciated all he did for me.

Too often, too many of us don’t get to do that. I know. It’s human nature.

We get caught up in our day-to-day lives and we think we’ll see so-and-so again in a week or two. Then they’re gone. And there was so much you wanted to say—so much you could have said—maybe, so much you needed to say.

That’s why what we do here this day is so important—to say humbly, sincerely, with great pride, “Thank you.” Thank you all, Village Pride Award Winners. Thank you, inspired leaders, behind-the-scenes miracle workers, movers and shakers, dreamers and good Samaritans. How wonderful you make our unique little corner of the universe…and how blessed we are to have you and your passionate commitment to make things better.

Over the last few days, I read over each and every one’s bio. Over and over, I found the same compelling verbs: volunteers, inspires, teaches, mentors, educates, provides, responds, collects, leads, battles, raises, contributes, assists, engages, organizes, impacts. And repeated adjectives: kind, positive, passionate, committed, selfless. All are such powerful words and you bring life to them repeatedly, willingly, fearlessly.

And the focus of your energy? Why, it encompasses the entire spectrum of life itself. You help children…teens…young adults…seniors…those that are less fortunate…those that suffer with disabilities…those who hurt mentally…that struggle financially…those that welcome new ones into their family…those who, sadly, say good-by to loved ones…those that work, that play, that retire…those who want to help themselves but cannot…those in business…those in life-enriching arts…those who give us so much love and support but cannot verbalize their needs—our pets and animals—and, yes, the very thing that serves as a stage for our entire existence—our ecology and environment.

This room is filled with so much positive, constructive energy…and, collectively harnessed, it is no wonder we are, indeed, a “beacon on a hill.”

Some 70 years ago, my father was a soldier. You fill the ranks today.

He fought to make the world safe. For our community, so do you.

He fought to deliver others from oppression. So do you.

He put his life on the line to make our planet a better place. So do you.

His war ended.

Ours does not.

As long as there as those in our corner of the universe that fear, want or need—we must, over and over, put on our gear and give battle.

In Greek mythology, Leander repeatedly dove into stormy seas to reach his love. You, in acting on your passions, also, repeatedly endure tempests. You do it because of your innate goodness and for what you’ve done, what you do and will continue to do.

Leander wanted to cross the Hellespont to be with Hero. I stand before a room of compassionate human beings who ARE heroes.

Thank you, for helping to make our universe, truly, the Southern Part of Heaven.

Freddie, I saw you in an alumni newsletter. I don’t know if you remember me from Parker dorm; I always knew you would stay a part of UNC. I’m glad you are still Involved! I found some old pictures of groups of us in the Avery, Teague and Parker group.