Elementary school was a challenging time for me. I was terribly unorganized and a bit of a mess. Once, in the third grade, my teacher was so frustrated by the slovenly state of my desk that she dumped it out on the floor in the middle of class. My handwriting was also really, really bad. On one sad occasion, this same teacher, for whom I still bear ill will some 37 years later, ripped up my homework in front of the class, threw it in the trash, and told me she would not grade it because it was too hard to read.

I was still struggling in the fourth grade, but then along came an assignment that was right in my wheelhouse, from a teacher more willing to navigate the eccentricities of my scribbles. We were assigned to memorize as many features as we could on the world map – countries, capitals, bodies of water and the like – and then transcribe them from memory on a blank world map. I rapidly filled the page, and went back for another, then a third, then a fourth. It was the first time that I can recall the feeling that I had the potential to perform well in school in a subject other than math.(1) I distinctly remember being proud of correctly labeling both the Aral Sea and Lake Chad. So, it is with some sadness that I report to you that these venerable bodies of water are on the verge of disappearing from the earth.

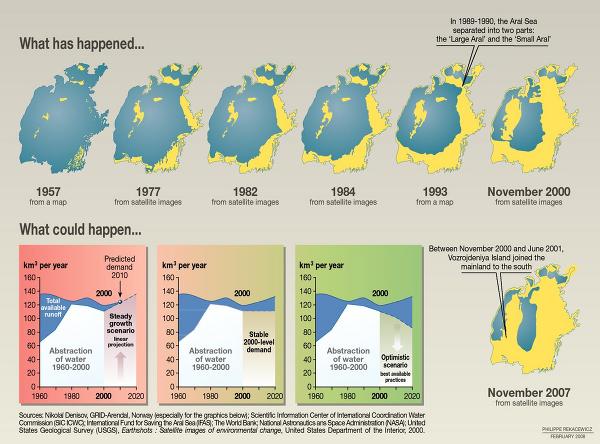

In 1963, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest lake in the world, with an area of 66,100 km2, making it a bit smaller than South Carolina. The Soviet Union stationed a naval fleet on the Aral Sea, and the local fishing industry employed over 40,000 people. Then during the 1960s, the USSR began to utilize – over-utilize – the rivers which fed the Aral Sea for irrigation of nearby land. The story of the resulting decline of the Aral Sea is perhaps best told by the series of pictures below.

In the span of my lifetime, the Aral Sea has lost 90% of its area and split into four small, distinct lakes, one of which went completely dry during the summer of 2014. In addition to the loss of the fishing industry and the natural beauty of the area, other bad things happen when a lake dries up. As the volume shrinks, the concentrations of salts, fertilizers and pesticides from run-off, and toxic heavy metals increase, making the water unsuitable for both aquatic life and human consumption. Furthermore, when a lake bed becomes dry it crumbles to dust, which is carried away by the wind. As a result, farmland downwind from the Aral Sea is suffering from excess salinity. In addition, people living in the surrounding area have high rates of respiratory disease and other ailments.

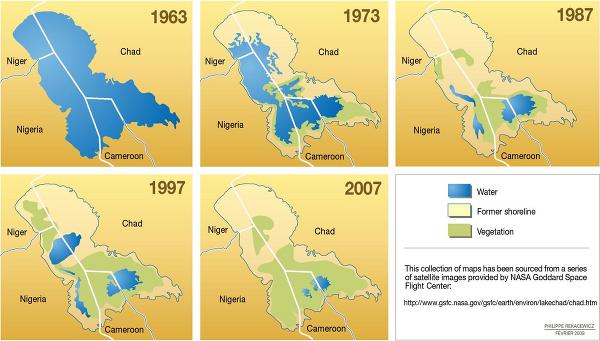

The story for Lake Chad is depressingly similar. In 1966, the year I was born, Lake Chad was the size of New Jersey, at 22,772 km2. As you can see below, Lake Chad is now only 5% of this size.

Like the Aral Sea, a significant factor in Lake Chad’s decline has been the use of the rivers that feed it for irrigation. In addition, overgrazing in the area surrounding Lake Chad has resulted in significant desertification. When vegetation (trees in particular) is lost from an area, fewer rain clouds are formed above. This sets up a self-reinforcing cycle which continues the decline of vegetation. Deprived both of input from the rivers that feed it and starved for rain, Lake Chad is withering away. Disputes about water rights for the remnants of Lake Chad have resulted in sporadic violence in the area.

Aside from reminiscing about my fourth grade geography test, what interests me about this story is the psychology of our collective response as humans to slow-developing problems. Despite the fact that it was clear for decades that these lakes, which are vital to nearby human life and well being, were on the path to catastrophe, we did nothing to stop it. It is just this sort of human behavior which gives me pause about the likelihood that we will take constructive and proactive steps to address other major environmental challenges, such as climate change.

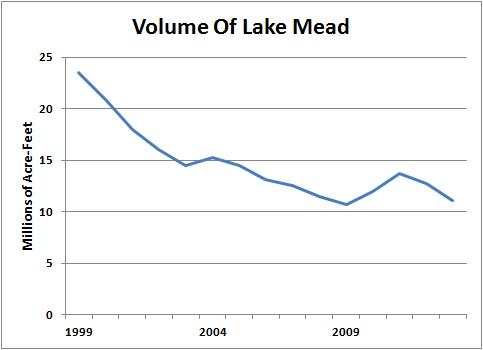

Lest we look askance at the peoples of Africa and Central Asia for not being good stewards of their natural resources, consider this graph of the volume of water contained in Lake Mead in Arizona and Nevada from 1999 until 2013.

During this short time, the content of Lake Mead has dropped by 53%. 53%! While I do believe it has become illegal in the city of Las Vegas to irrigate your lawn, we have not yet made any meaningful changes to address our own looming water crisis. I’ll leave it to your judgment how low the level in Lake Mead will need to get before we here in the United States start to rethink some of our water intensive habits like eating beef or using more and more electricity every year.(2) In the meantime, I’d encourage your 4th grader to hurry up and study Lake Mead before it disappears.

Have a comment or question? Use the interface below or send me an email to commonscience@chapelboro.com. Think that this column includes important points that others should consider? Send out a link on Facebook or Twitter. Want more Common Science? Follow me on Twitter on @Commonscience.

(1) For parents to whom this story sounds like your child’s experience in elementary school, let me share the rest of the story with you. My handwriting continued to be a significant problem until the 9th grade when two important things happened. First, my 9th grade biology teacher refused to grade my work in its deplorable state. Because of her, I adopted a practice that I continue to this day. When writing by hand, I go slowly and only use capital letters. I got an A in the class. Secondly, I took a typing class in the 9th grade. Once I learned to type, the task of writing a book report or an essay was no longer incredibly daunting. Once I hit my stride in 9th grade, I went on to get a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering. So don’t lose hope.

(2) It takes 2,000 gallons of fresh water to produce a pound of beef, compared to 140 gallons to produce a pound of wheat flour. Electric power plants, including coal, natural gas, and nuclear account for 41% of the use of fresh water in the United States.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines